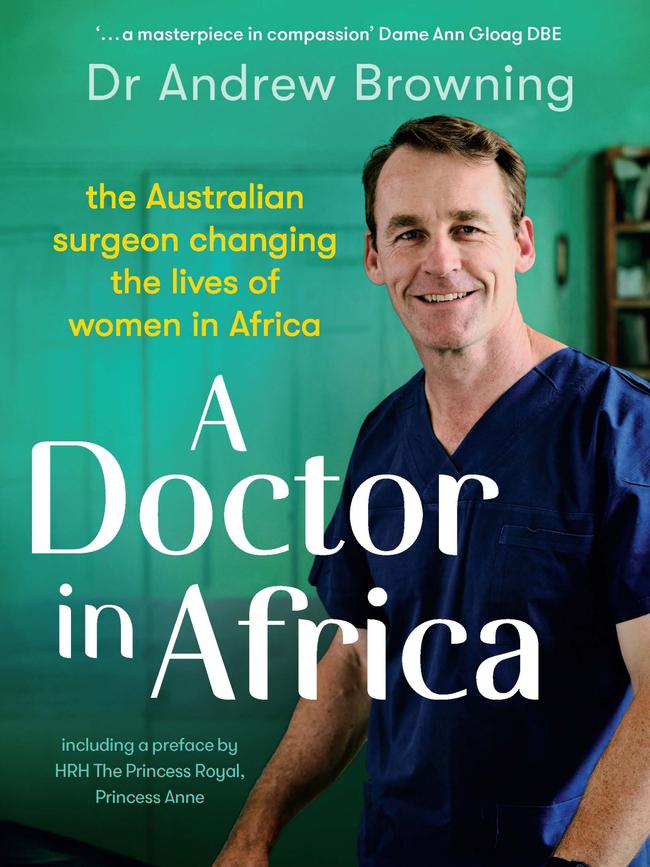

Dr Andrew Browning shares his inspiring story in A Doctor In Africa

Dr Andrew Browning has saved 7000 pregnant women around the world — but not everything always goes according to plan. WARNING: Graphic

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

In medical circles Australian obstetric surgeon Dr Andrew Browning is recognised as a world leader in his field, credited with saving the life of more than 7000 pregnant women through his pioneering surgical techniques.

But in the broader public, his story and the extent of his incredible lifesaving work over nearly two decades in Africa is not as widely known.

That could well change with the Bowral doctor penning his heart-warming story and getting endorsement from HRH Princess Royal and mother-of-two Princess Anne who has now publicly “applauded” his work and praised his uplifting book for offering a sense of hope to all prospective mothers who may suffer complications with birth.

For a then young Dr Browning, born to a prominent Australian family and last year granted an extraordinary permit to travel abroad to save lives in the midst of COVID-19 lockdowns, being an obstetric fistula surgeon was a lifetime career that actually found him.

Below an edited extract of A Doctor in Africa.

Right in the heart of Africa are two tranquil, beautiful and verdant countries, Burundi and Rwanda, They are green, lush and mountainous, and oft described as the Switzerland of Africa. Different tribes from different people groups have been living there since time immemorial. The largest tribal group is the Hutus, a Bantu people group typical of the Sub-Saharan people, stocky with wide facial features. The smaller tribe, the Tutsis, are a taller, traditionally cattle-herding people.

These two tribal groups have been living side-by-side for generations, occasionally coming to blows, occasionally living in harmony but with much intermarrying.

In October of 1993, the newly elected Hutu president of Burundi, Melchior Ndadaye, was assassinated by extremist Tutsi army officers. Pressures between Hutus and Tutsis in the region were increasing and some say that the mass extermination of the Tutsis by the Hutus was being planned for years before that.

The assassination of Ndadaye poured fuel on the fire and it is estimated that by the end of 1993, there were up to 350,000 refugees in Western Tanzania, mainly from Burundi, but more were to come.

Then on 6 April 1994 in clear skies on final approach over Rwanda’s capital, Kigali, the presidential Dassault Falcon jet, was struck by two surface-to-air missiles causing the plane to erupt in a ball of yellow flames before it crashed violently into the garden of the presidential palace, exploding on impact.

On board the plane were three French crew and nine passengers including the Hutu president Juvénal Habyarimana. There were no survivors.

Just as the assassination of Austria’s Archduke Ferdinand on 28 June 1914 set off a chain of events culminating in one of the deadliest conflicts in history, WWI, the assassination of the Rwandan president was the impetus for one of the bloodiest events Africa has ever been involved in – the Rwandan genocide.

The clash of cultures and the tussle for power between the Tutsis and the Hutus had come to a violent head.

Within hours of the attack, the mass slaughter of Tutsis began, resulting in the genocide of hundreds of thousands of people in the following three months. Overall, 800,000 (some estimate the number went beyond a million) Tutsi and Hutu moderates were killed between April and July 1994 by the militia. Thousands of Tutsi women were kidnapped and kept as sex slaves. Using machetes, neighbour slaughtered neighbour and it was reported that some husbands killed wives fearing retribution if they did not act. It was the most rapid genocide ever recorded and has been compared to the Nazi Holocaust because of the ferocity and cruelty of the brutal attacks.

Fearing revenge attacks, two million Hutus then fled across the borders to Zaire (now the Democratic Republic of the Congo or the DRC), Tanzania and Burundi.

In 1993, I had just begun my elective term as a young medical student. Even though I was studying at the University of Sydney, I was able to undertake some of my in-hospital training overseas.

Many people took the chance to do some research in Australia; others worked in England or America while a few of us chose more remote locations. Recalling the Tanzanian hospital I had heard about as a six-year-old at Sunday school from an Australian missionary nurse, I decided to go to the same place. The instability in the region was rising and news had reached Australia of the hundreds of thousands of refugees in Western Tanzania – just where I was off to. At that time, back in 1993, there were no phones let alone internet at the hospital and electrical blackouts were common. Letters to arrange my work at the Tanzanian hospital took around six weeks at best to return, sometimes 12 weeks. We heard little and assumed all was well for me to go. Boarding my flight at Mascot Airport in Sydney, I was excited about what lay ahead.

I travelled alone towards Murgwanza Hospital in far northwestern Tanzania.

As it happened, the hospital was right where the borders of Burundi, Rwanda and Tanzania meet. The tranquillity of the setting where I was staying in Murgwanza was in stark contrast to what was happening in the killing fields in nearby Rwanda and Burundi. This was the same land that I looked over from the peaceful veranda each night watching the sun set in a blood-red sky.

When I arrived in Murgwanza in Tanzania in 1993, I was just a fresh-faced 23-year-old man, having experienced little outside of Bowral and the University of Sydney. That was all about to change as I witnessed some of the 20,000 refugees fleeing from Burundi and Rwanda arriving in the areas around the hospital.

I began each day in the hospital with eyes wide open, struggling to take in all the differences to home but thrilled about making a difference with so little.

One of my first experiences in an African hospital was seeing a young man who had been savagely bitten by a hippopotamus after rowing his boat in the Kagera River on the Rwanda – Tanzania border. But the next patient was more typical of what I would encounter during the rest of my career.

He was a newborn who was floppy and with no discernible breath nor heartbeat. The mother had been in labour for too long in the village before she came to hospital and the doctors hurriedly performed a caesarean. But they were too late – the baby’s heart had stopped.

As I searched my mind to work out what to do for this newborn, I knew that in Australia I would be able to press a button on the wall and an army of paediatricians, intensivists, midwives and others would come to my aid, racing through the door and nudging me out of the way to take over with highly advanced procedures to save the newborn. Not in Tanzania.

This baby had one chance besides me, an inexperienced med student still at university, and it was the nurse assisting me.

‘Nurse, quickly pass me the resus bag,’ I said as I reached for perhaps the most vital piece of resuscitation equipment needed in this sort of situation.

‘Doctor, it does not work properly,’ the brown-eyed Tanzanian midwife replied in slow broken English.

The small black resuscitation bag had a massive hole gouged into its side, rendering it completely useless. The nurse did not appear surprised. Perhaps this was the norm for this part of the world, I thought. My stress levels rose. Time was of the essence before this baby had irreparable brain damage. The race was well and truly on.

‘Quick nurse, place two fingers in the middle of the baby’s chest just like this below the nipples,’ I urged and we started CPR.

The nurse did her job beautifully and didn’t need me to instruct her at all.

With the resuscitation bag rendered ineffective, I resorted to old-style CPR with mouth-to-mouth-and-nose-resuscitation. My dry mouth was covering the baby’s nose and mouth as I puffed air into his lungs. The taste and smell of amniotic fluid and vernix (the fluid and waxy covering of babies inside the womb) was still present and made me gag. The nurse was doing an admirable job pushing the oxygenated blood around the body.

We tried injecting the baby with lifesaving adrenaline straight into his heart and we were doing everything possible with what was available but after 30 or 40 minutes or so we knew that our efforts were futile. The baby boy was dead.

Feeling soiled, sweaty and defeated after our intense battle to save this little boy, we trudged slowly towards the mother. She had been in labour for too long in the village. She had needed a caesarean much earlier.

My joyful job as the trainee was usually to receive the baby and hand him to the mother for bonding. Now under completely different circumstances, I handed the lifeless limp form back to the mother who was now in the recovery area, a small, poorly lit and ill-equipped spot outside theatre.

She held her child with empty glassy eyes, and stared into mine – no anger, nothing said, just a look of complete helplessness and loss. I feared that I would see many more eyes like this in the days and years ahead if I decided to make this my career.

All royalties from the sale of the book will be donated to the Barbara May Foundation.