Outback expert David Batty found fashionistas, musicians and Top End don’t mix

David Batty knows Outback Australia better than most – and has had his share of hairy moments. In Batty’s Bush Bible, he tells why fashion photographers, musicians and the Top End don’t mix.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

One of the more random jobs I did while running a television production company in Alice Springs was organise a fashion shoot for a major German fashion label, in January 1993. As part of the circus they sent a German photographer – let’s call him Konrad – and his assistant.

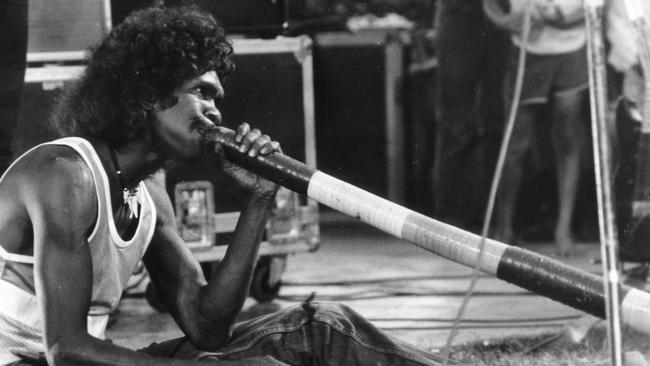

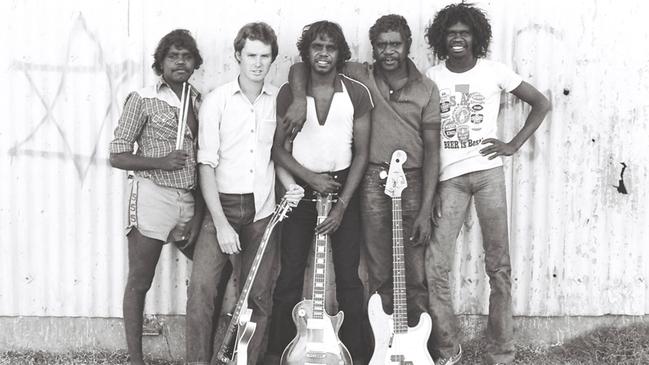

After a day or two of shutter shenanigans, I informed the fashionistas that I had to go bush on a shoot for the now legendary filmmaker Rachel Perkins, following the various members of the also legendary Warumpi Band – an Aboriginal group with a white singer-guitarist.

One stop would be at Arnhem Land in the Top End filming the flamboyant singer George Rrurrambu at his outstation island homeland near Elcho Island.

When I explained this to Konrad, he wanted in, along with his stylist. ‘Great. We need stills,’ Rachel said. ‘So long as they pay their own way and we own the pics.’

We flew from Alice to Darwin, then by small plane along the coast of Arnhem Land to the small Aboriginal community of what was then called Elcho Island, now known by its Yolngu name, Galiwinku.

George met us at the airstrip and took us into the community. We needed a boat big enough to take our crew, gear, swags, George, his brother, half a dozen ladies and a few kids out to George’s island outstation some distance from Galiwinku. We ended up with an older Yolngu man who had a battered six-metre aluminium dinghy – and who greeted us with glazed eyes and a slow smile from a heavy night on the kava.

‘How far out to your island?’ I asked George casually as we waited on the banks. ‘Not really far,’ he replied simply. ‘Should we buy some tucker?’

‘Nah, we blackfellas, mate, and this our Country,’ he said confidently. ‘Plenty tucker out there.’

As we zoomed along a wide channel fringed with thick, dark mangroves, the Germans were transported into a blissful state of awe and wonder. When we reached the open ocean, with night almost on us and the island a mere speck on the horizon, we paused to discuss our chances of getting to the island alive. Then it all went wrong.

The choppy water and heavy breeze of the open ocean was slowly pushing us closer to a rocky headland. Then the motor ran out of fuel and died. As we drifted, a razor-sharp reef was becoming visible under the boat.

George and his brother jumped overboard in a vain attempt to push the heavily rising and falling lump of aluminium away from the reef and the crashing, rocky shoreline just metres away.

Waves were now sloshing over the side of the dinghy, and the women and kids were not happy. The youngest ones were broadcasting their screams to all on board, who were hanging on for their lives.

The Germans and I managed to slosh some spare petrol into the tank and eventually the motor rumbled and revved back to life – but as a wave slammed us down once again the propeller hit the bottom and snapped the shear pin that kept the drive shaft connected and the propeller turning.

As if by a miracle, somehow the boat was moving ever so slowly forward even with the shear pin broken.

Exhausted and wet, and with the light fading, we chugged our way back into the channel and pulled up at a quiet cove with a placid beach. We silently unloaded the boat and collapsed on the sand. This was before the invention of mobile phones, and with no radio or flares we were as stuck as a buffalo in mud. The propeller on the boat didn’t have enough guts to take us anywhere and was abandoned. Everyone wandered off to one of two camps: us and the Germans, or George and his family. We quietly got fires going, stretched out on the sand, meditated on our near-death experience then gave in to our heavily sunburnt eyelids.

The next day we tossed around rescue scenarios until the idea of being found faded, along with our memories of cold beer, comfy beds and, above all, food. We were in the height of the unbearably hot wet season, with humidity you could cut with a machete. The bush at the back of the beach was impenetrable, crocs were eyeing us off from the water’s edge, and the mozzies and sandflies could almost carry you away. On the upside, everywhere you dug on the steep little beach made a pool of brown but perfectly drinkable water.

Luckily, George and his family had been busy hunting for food, which amounted to several stingrays and a pile of oysters the size of plates.

On the second night of camp Survivor, Rachel’s glamorous sound engineer realised that she and Konrad were cosmically and spiritually connected through their prior devotion to Bhagwan Shree Rajneesh, the leader of the orange-clad cultlike Rajneesh religious order. Thanks to this shared higher-order consciousness, the pair, along with the stylist, decided now was as good a time as any to crack open a jar of preserved magic mushrooms the Germans had miraculously acquired during their travels. Managing to restrain myself from the ingestion of mind-altering fungi, I now had to endure the terrified trio as they imagined crocodiles crawling towards our cluster of swags and saw coloured balls and flashes in the sky, none of which was helpful.

By day three, the stylist had broken out in a nasty sunburn rash and Konrad was plotting our escape plan.

‘David,’ he said, frenzied, ‘we leave the others here and take the boat to the other side of the channel.’

‘And then what?’ I replied.

‘We get help.’

‘From … ?’

My lack of enthusiasm for his plan brought on a full-blown hissy fit.

‘We must get off this place!’ Konrad cried. ‘I need to get to Sydney! I have an appointment with Peter Garrett in two days!’

‘Bugger,’ I muttered in faux sympathy. ‘Don’t see that happening.’

Day four, and the novelty of oyster steaks and roasted stingray balls was wearing thin. There was no sign of being rescued and no likelihood of it. As much as I wanted to get out of our predicament, I had to work on just staying calm. To survive being stuck in the desert is one thing, but getting off a croc- and mosquito-infested island in the middle of a remote and isolated coast in the height of the wet season had me stumped.

I approached George, who seemed unfazed by the events and almost seemed to think it was situation normal.

‘The Germans really need to get to Sydney,’ I said.

‘Okay, we sail back,’ he said. ‘Two o’clock today.’

It was as if he’d known how to get off the island all along, but was enjoying being on home ground. With little ceremony, he smashed his way into the thick scrub and came back with some long, thin saplings. He asked me for sheets from my swag, and some wire and gaffer tape from my kit bag. In no time he’d fashioned a fold-out Macassan-type sail, the ones that look like a big V.

When everyone was back in the boat, George lashed the sail to the front. Then our Yolngu companions pushed us out into the middle of the channel with little fuss. But the poor Germans had had enough, and grizzled away in their native tongue. I was also pretty annoyed that the whole event had happened, but Rachel was cool, calm and content.

At around 2pm, as if by magic and just as George had predicted, a gentle breeze hit our faces. It became stronger. I will never forget what the Yolngu call that lifesaving wind – murai yil yil.

The breeze grew solid, consistently pushing against our swag sail. We slowly cruised back up the channel using the useless outboard as a rudder. At about 8pm, we pulled up at the little beach on the other side of Elcho Island.

George and his crew seemed fine, but a dark cloud hung over the rest of us. The Germans had become solemn and demanding; Rachel and the sound engineer were quiet and subdued; I was just totally over the entire situation. To make things worse, we all had serious sunburn.

Then it started raining.

After another night without food or accommodation – there was no hotel, so we sheltered on the primary school veranda – we flew out first thing in the morning.

In Sydney, the Germans rescheduled their meeting with Peter Garrett and Midnight Oil, and invited Rachel, the sound engineer, George and me to the most expensive restaurant in town. Needless to say, nobody ordered the oysters.

Following our Survivor reunion dinner, we all went up to the Germans’ penthouse suite at the top of the Shangri-La Hotel at Circular Quay, where bottles of French champagne were waiting. We lolled about, intoxicated by the views, laughingly recalling moments from our boat trip to hell.

Then Konrad gripped my shoulder. ‘David, that trip was so much fun,’ he said earnestly. ‘I would like to come with you again …’

This is an edited extract fromBatty’s Bush Bible by David Batty: available now, published by HarperCollins