Cher reveals the truth behind her early flops, Sonny’s drugs disaster, dating ‘asshole’ Gene Simmons and that police cell nightmare

Sonny and Cher were on top of the world – until his drug culture move backfired and blew up their career. And all the time, Sonny was hiding his own drug secret.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

From a tough childhood to the heights of fame as a singer and actor, Cher’s life has been unique. Her new memoir is bursting with extraordinary stories – and in this exclusive edited extract for Australia, the A-list icon shares a few.

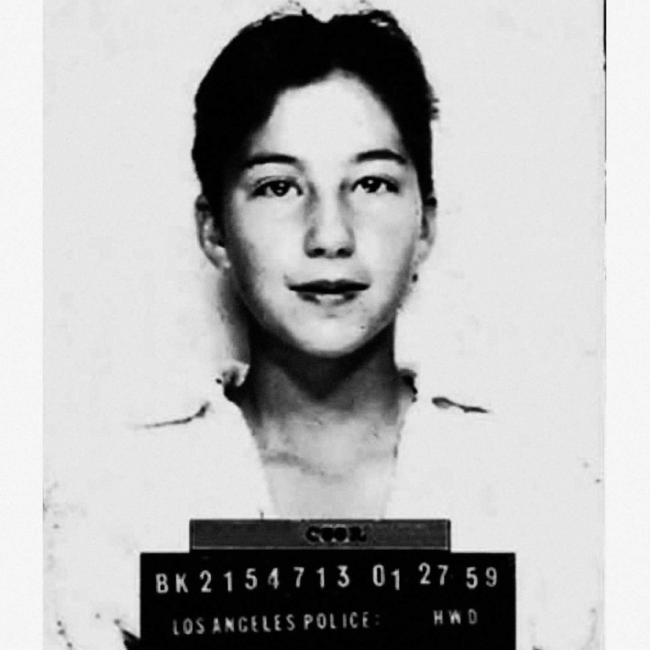

MY FAKE NEWS POLICE NIGHTMARE

My mother, my sister Gee and I moved a lot. Gee kept a list of all the schools she attended and claims it numbered more than twenty-five. I never kept count.

In January 1959, I started at Walter Reed. One night I went out with two of my friends and one of their boyfriends. We went for a ride in a ’57 Chevy, which my friend’s boyfriend double-parked at the now-iconic Kirkwood bowling alley. He ran inside for something, telling us, “If anyone comes, tell them I won’t be long.”

We waited and waited, but other drivers started honking their horns for us to move out of the way. I slid into the driver’s seat, slipped the Chevy into gear, and circled the parking lot to let them pass. Still the boyfriend didn’t re-emerge.

“Let’s drive around the block, Cher,” my girlfriends urged, so I did as they asked. Thrilled, they suggested, “Now drive us to Johnie’s drive-in to get orange juice for our vodka,” so I did that too. They’d stashed the vodka in one of their purses, but when we swung into the drive-up parking spot, a squad car suddenly appeared behind us, lights flashing.

It was humiliating to be pulled from the Chevy by armed officers and given the third degree.

Scared out of my wits, I tried to explain, but the boyfriend had reported his car stolen, so we were taken to the police station.

Everybody else’s parents came as soon as the police called, but Mom was out and they couldn’t get ahold of her. By the time it was midnight, an officer moved me to an empty holding room so that I could at least lie down. Exhausted and emotionally wrung out, I was finally falling asleep when I heard a noise from underneath the bunk. A hand suddenly shot out and grabbed my ankle. Crawling out, a wild old drunk started ranting, “Hey, you bitch!” I kicked him off, screamed for help, and remained glued to the wall until officers rescued me and closed the door on the bum they’d forgotten was sleeping it off in there.

My mother eventually came for me at 2am and, after taking one look at my tearstained face, decided that I’d been punished enough. The worst part was that I never saw those girlfriends again, as their parents decided I was a bad influence and warned them to keep away from me.

As a humorous postscript, years later someone pulled a photo of me from my junior high school yearbook in sixth grade and made it look like a police mugshot, although the cops never took one.

After I became famous, that picture appeared in newspapers and magazines around the world as the real thing – an early case of “fake news” that made me laugh.

OVER BEFORE WE BEGAN

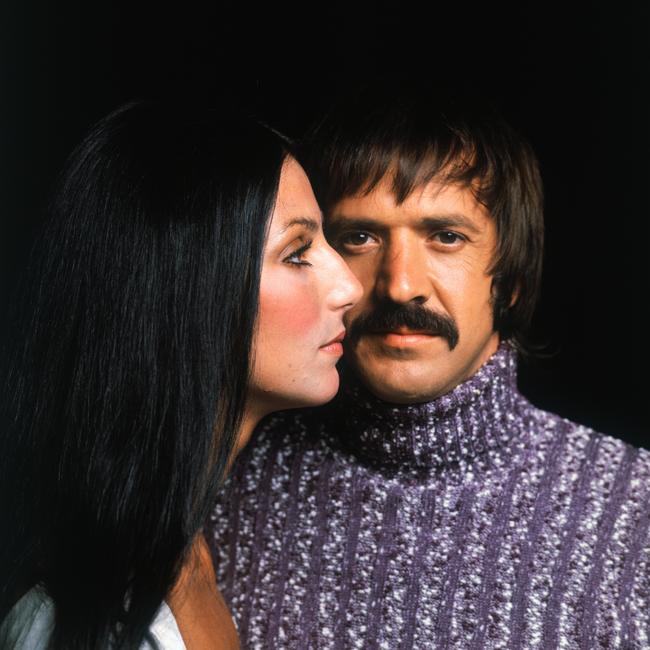

For much of 1964, my partner Sonny Bono and I worked in Phillip Spector’s studio and witnessed the Ronettes become major stars. When they went on tour to England, their support band was a new British group called the Rolling Stones. Ronnie had a fling with guitarist Keith Richards even though her mother was there as chaperone.

Sonny’s dreams for me were still being stalled by Phillip, who insisted my voice wasn’t commercial enough and had the register of Paul McCartney. Sonny knew he had to try to find me the perfect song and create the right image to make it a hit.

Fooling around with the five chords he knew, he persuaded Jack Lewerke, who had recently founded the record company Vault, to record and release a song he wrote called “The Letter.” To be honest, I didn’t like it. The disc was released in February 1964 as by “Salvatore Bono and Cher La Piere, also known as Caesar & Cleo.” It bombed.

Our next release was “Love Is Strange,” a 1956 hit written by Bo Diddley. That record tanked.

Sonny wasn’t a genius songwriter, but he was clever enough to be influenced by what he heard so that he could keep up with the trends. The problem was that things were changing so fast. Beatlemania had hit America and the young British boys in sharp suits and clipped hairdos were all anyone could talk about.

Cashing in on their popularity, Phillip Spector wrote a song called “Ringo, I Love You,” as if it were sung by a devoted fan to the drummer Ringo Starr – and decided that I should be the one to record it. His only proviso was that I change my name to Bonnie Jo Mason to sound all-American. It was released in March 1964 – and the feedback was terrible. My voice was so low that DJs thought it was one man singing a love song to another when homosexuality was still illegal. My single stiffed out of the gate. Bonnie Jo Mason was a flop.

When I listen to my early numbers, I cringe. I sounded so nasal because of teenage allergies. I’d also recorded an album of covers for Liberty Records, but they didn’t like the way I sounded either, so nothing came of that. The failure of both convinced Phillip that he was right about me. Sonny stopped hassling him to give me another chance and I stopped singing around the house.

Devastated, I was convinced that my career was over before it had even begun.

DRUGS: A NAIL IN OUR COFFIN

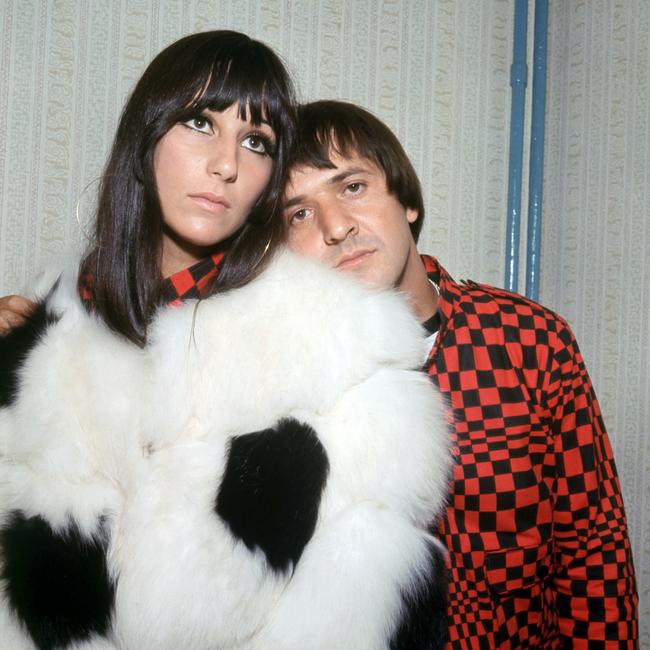

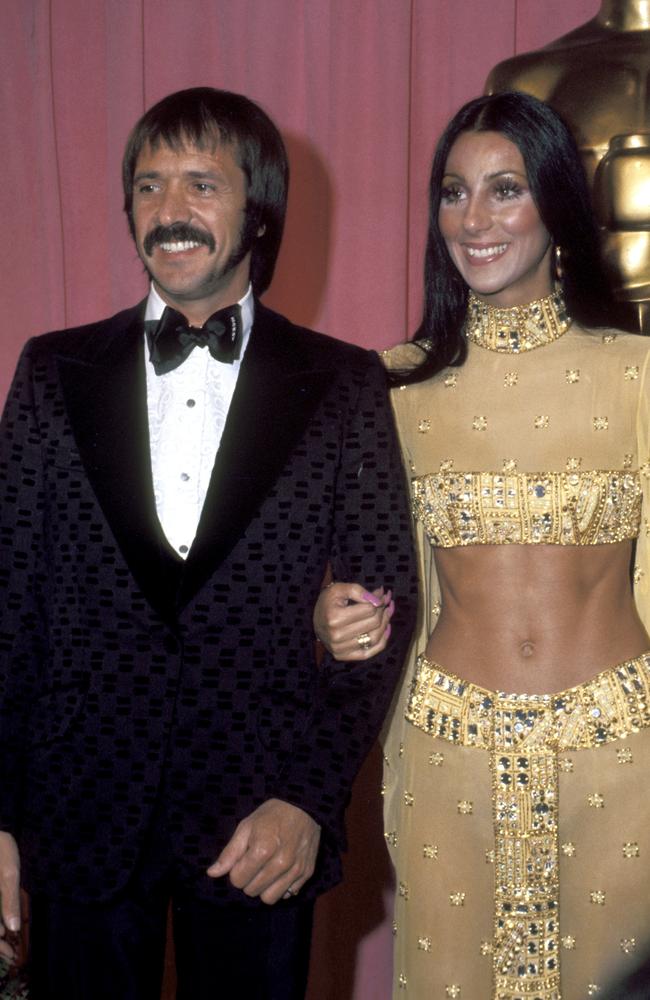

By 1965 the hits – like Baby Don’t Go and I Got You Babe – were landing, and suddenly we were huge, as Sonny and Cher. Sonny was determined to make me a star as bright as Tina Turner, but world events were already changing the dynamic of our industry beyond his control. The midsixties brought in the counterculture, with ideas advocated by people like Timothy Leary, the Harvard psychologist who recommended the use of psychedelic drugs for mind expansion.

Leary became famous for his “Turn on, tune in, drop out” message, which I thought was dumb. So, while everyone else was tripping, playing acid rock, or marching in the streets to protest the Vietnam War, Sonny and I were the straight, square couple who sang middle-of-the-road songs, didn’t engage in drug culture, and now in the era of free love we became uncool for being married.

For some reason Sonny felt compelled to abandon his antipolitical stance and he released a statement condemning the use of marijuana, which made us look like part of the Establishment and alienated our younger fans. I didn’t want to smoke pot myself, but I didn’t care if other people did. His antidrug stance seriously backfired, because our record sales dropped almost immediately and offers began to dwindle. Our agency even switched us from the musical concerts department to the personal appearance department, which we knew was the first nail in our coffin.

Keeping us relevant and in the public eye required a great deal more time and energy after that, and the more Sonny took on, the moodier he became.

Looking back, I think some of his mood swings at this time could have been because he was starting to abuse prescription meds – as I would learn when I discovered his stash.

**

Sonny’s behavior could be erratic and moody, but it never occurred to me at the time that he might secretly be taking drugs himself. He was so staunchly antidrug I never dreamed this could be true. But one day, I saw something I wasn’t supposed to see. I was resting on our bed when our bodyguard Big Jim wandered through our bedroom with something that he placed in the cabinet in Sonny’s bathroom. I didn’t think anything of it, but after Jim left, I went looking for a razor to borrow from Sonny to shave my legs, and what I found instead was something I didn’t expect.

Inside the cabinet was a square white-plastic bottle about seven inches tall with hundreds of blue Valium pills in it, the kind of container a pharmacist stores bulk pills in before divvying them into individual prescription bottles.

Sonny’s bathroom was private, and I knew intuitively that I shouldn’t go in there, but I’d had no idea it was because he’d secretly been taking the Valium and prescription painkillers he kept for pain from his kidney stones. Had I known back then, it would certainly have explained the mood swings that made him so hard to read, or the nights he’d shake me awake to talk about something. I don’t suppose for one minute he thought of those pills as the “drugs” he publicly condemned like pot or LSD. As I was soon to find out, this wasn’t his only secret.

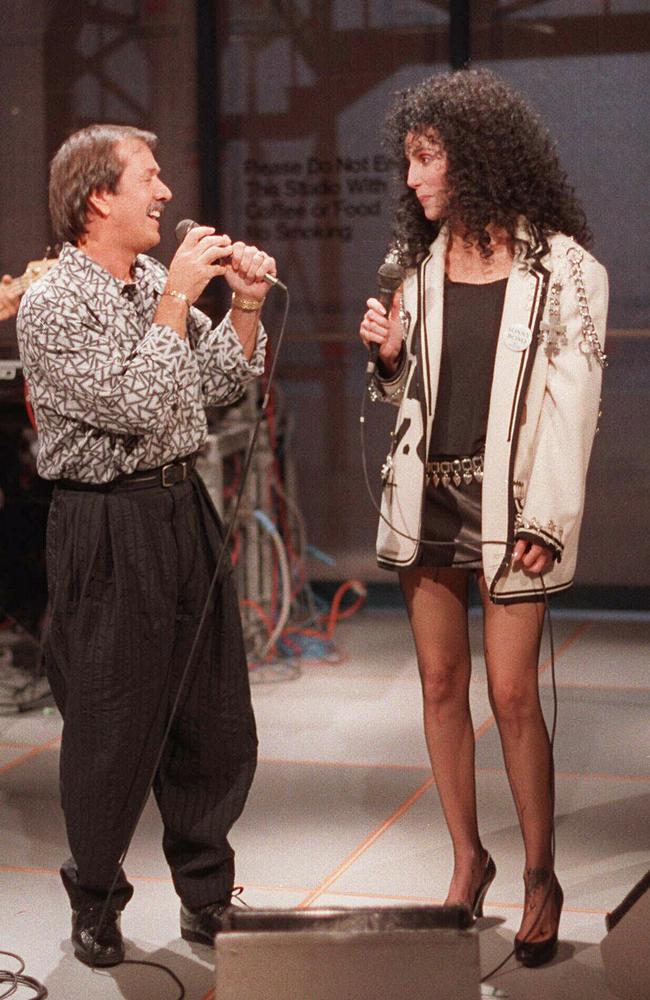

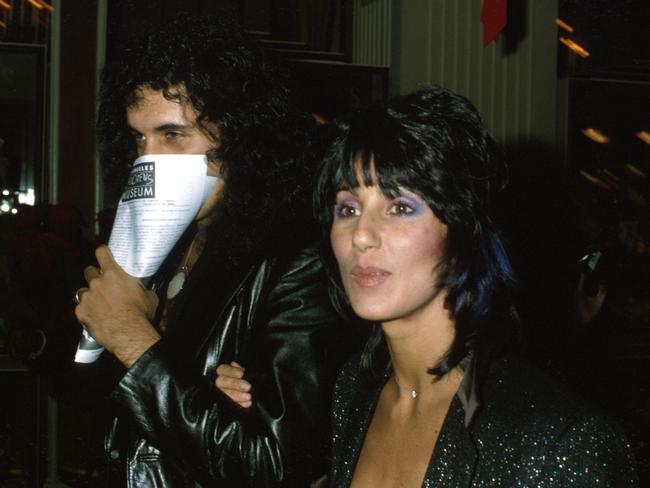

DEMON GENE AND A DISCO HIT

One night in 1978 Neil Bogart, the head of my record label, invited me to a reception, where someone asked if I’d like to meet Gene Simmons. I replied, “Oh God, yes! I’m a huge fan. I’ve seen all her movies,” mistaking the fire-breathing, tongue-waggling, ghoulish Kiss bass player for Jean Simmons, the British actress. It was an embarrassing mistake, but one I quickly rectified by asking Gene to sign something for my rock-loving daughter Chas, who I knew would be thrilled.

Onstage, Gene wore black leather and his signature black and white makeup, and was known by his fans as “the Demon.” In the real world, he looked like a pretty regular guy, but when he spoke, his voice was a deep rumble, like he was trying to be sexy. I laughed and asked him, “Is that your real voice or do you just always talk that way?” which embarrassed him. I didn’t say it to be mean – it was a real question.

After that, he started speaking normally and turned out to be very nice and surprisingly polite, albeit with a rock god ego. An Israeli-born former sixth-grade teacher — he told me he realised he didn’t really want to be a teacher, he’d just wanted to be up in front of the class — he was four years younger than me and an only child devoted to his mother, who’d survived a Nazi concentration camp. Best of all, he was stone-cold sober and had never had a drink in his life. By the end of the evening, I was impressed.

“How about I take you home?” he suggested – then stopped in at his. On the drive to my house, he told me he would drop me off, then go to his hotel so he could pick up some things for Chas and bring them back after. I said okay, and he came back with like five thousand pieces of Kiss merch. I think Chas thought she’d died and gone to heaven.

Gene suggested we go out on a date the following night to a Tubes gig. I asked if I could bring my close friend, the actress Kate Jackson – and Gene spent the entire night flirting with me and Kate. When he left, we looked at each other and both chimed, “What an asshole,” so I figured that was that. He called the next day to apologise, but I told him neither Kate nor I liked him.

Soon after, he left to play in Japan but called me while he was away. We talked so long on the phone he ended up with a $2,800 telephone bill. That’s when he blurted out that he loved me. We hadn’t even kissed. We’d only been out once before he left. What is it with these men? We began what turned out to be a surprisingly nice relationship.

So that he could see me more often, Gene got a bungalow at the Beverly Hills Hotel where he could stay while he was in town from New York. We didn’t do so much as kiss at first, because I didn’t want to yet. I’ve always felt that I don’t want to sleep with someone until I’m sure I’ll be happy to wake up next to them the next morning. So Gene and I got to know each other; we talked and we walked. I even took him jogging on the beach. He called me “Puppy” and surprised me for my birthday with “I Love You Cher” written in the sky above the Beverly Hills Hotel, before a full choir and a marching band marched into our bungalow, through our room, and back out.

If that weren’t enough, he rented an army tank; filled it with my favourite chocolate bars, Snickers; and had us driven down Sunset Boulevard to Le Dome restaurant, where friends, family, and circus acts were waiting.

My children Chas and Elijah also loved having “Genie” around. Being around kids, he could just be the kid he was inside. We became a merry band of travellers, especially after Gene set my sister up with his bandmate Paul Stanley and they started dating.

**

In 1978, I wanted to record a rock album, branching out into the kind of music I liked to listen to. But Neil Bogart, who’d launched the careers of Donna Summer and the Village People, said it would be better if they broke me out as a disco artist first.

“Everybody’s doing disco these days,” he assured me. “Even the Rolling Stones.” Although I loved to dance, I didn’t think I was going to be a disco queen. I also worried that I wouldn’t be welcomed into that community. But I trusted Neil’s judgment. I went along with his suggestion and recorded the album Take Me Home.

Once I recorded the title track, I felt good about it. We played the song back in the studio and everybody liked it. Sometimes the people in the room have the right instinct and sometimes not. In this case we were right. The album reached number eight on the Billboard charts and stayed there for five months.

Gene came up with the concept for the album’s cover: a photo of me in a gold bikini with large gold wings attached arm cuffs, and a headdress under a pleated gold cape. I looked like a barmaid from Valhalla.

This is an edited extract from Cher: The Memoir, Part One. Published by HarperCollins in Australia on November 20, 2024. Part Two is expected in 2025.

Read Cher’s exclusive interview only in Stellar magazine this weekend.