Abigail Dean’s new novel centres around a school shooting conspiracy theorist – and he could be any one of us

Conspiracy theorists are nuts, right? Not always. A confronting new book about the aftermath of a tragedy shows they can be disturbingly more relatable than most of us wish to believe.

Books

Don't miss out on the headlines from Books. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Back in 2019, when I started writing a novel about conspiracy theorists, I thought I knew what to make of them. I had spent enough time on Reddit. I had seen Infowars banned from YouTube, Apple, and Facebook. I had read tweets doubting the authenticity of the bombing at the Manchester Evening News Arena in 2017, when 22 people were killed in my hometown. Conspiracy theorists were people who wore tin foil hats, hid behind avatars, and spent New Year’s Eve awaiting the annual apocalypse.

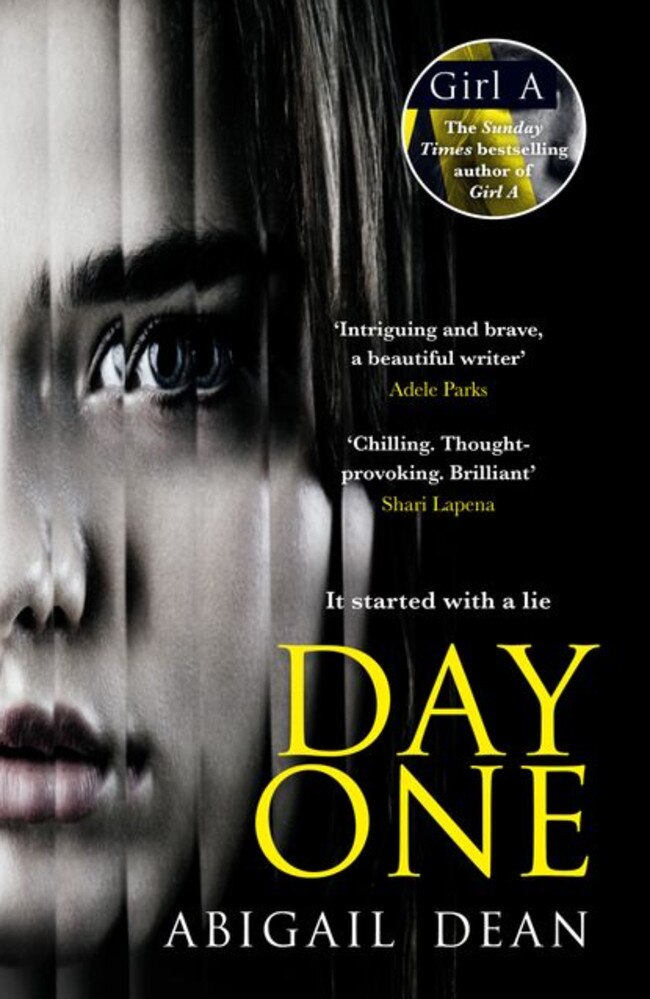

InDay One, a conspiracy theorist becomes obsessed with perceived inconsistencies in survivors’ accounts of an attack at a school. He infiltrates a small, grieving community and mistakes human foibles for a cover-up. But the book wasn’t working. Half of the novel was to be narrated from the conspiracy theorist’s perspective, and the character was despicable. He was cold and deranged. I could imagine readers skipping his chapters, eager to return to the families he torments.

I was still feeling pretty helpless about the novel when 2020 rolled around. Everybody knows what happened next. The Covid-19 pandemic spread, and the world stuttered to a halt. In the UK we were ordered to exist in isolation, branded – with comical charm – as “bubbles”. From the two-bedroom flat where I spent lockdown, I watched protesters target medicine watchdogs, hospitals, and NHS test centres. I took my daily walk past lampposts where anti-lockdown stickers were pasted, describing immunisation and face masks as the Incremental Steps To Total Enslavement. Conspiracy theories had spread, as deftly as the virus, and for the first time I looked on their carriers not with disdain, but empathy.

In a time of turmoil, conspiracy theories provided a story of order. During the course of 2020, my grandmother and uncle died. Lockdown laws prohibited me from attending their funerals or visiting my grieving family. I understood the desire to squeeze this strange, terrible time into a narrative; and if that narrative provided comfort – if the pandemic was all just one government-engineered hoax – all the better. When Professor Cynthia Wang (Northwestern University) was interviewed about Covid-19 conspiracy theories in 2021, she admitted that the theory that microchips are hidden in vaccines provides for “a very clear and compelling story. That’s a much more comforting story than saying, ‘I don’t know if these vaccines really work’”.

I find this simplicity in the speeches of Donald Trump, one of the world’s most prominent peddlers of conspiracy theories. Like a story you would tell to a child, his world has baddies (the Democrats; undocumented immigrants; CNN; most recently, Kevin Rudd) and goodies (Trump himself; the “hostages” imprisoned following the 6 January 2001 US Capitol attack). When the 2020 US election went against him, it wasn’t a culmination of socio and economic factors and his own failures, but a tale of good versus evil. All writers love a good story, and manipulation and intrigue is much more seductive than the real narrative of the universe, with all of its uncertainties and absurdities and unfairness. It is also much pithier, better teased in soundbites and Stories.

And the more I read about conspiracy theories, the more my cynicism softened. This wasn’t a great surprise. I was trawling the same websites and skimming the same comments. Some research has found that YouTube’s algorithm, for example, can direct users towards ever-more extremist content. What really did surprise me – what made me think, begrudgingly, fair enough – was the number of conspiracy theories that have a kernel of truth at their heart.

The most surprising example of this relates to vaccine scepticism. It is easy to laugh at the prospect of Bill Gates using the COVID-19 vaccine rollout to gather data and track the world’s populations. But it is harder to laugh once you know that government agencies have used this exact tactic in the past. In 2011, when the CIA was trying to track down Osama bin Laden in Pakistan, they organised a fake vaccination rollout in the town where they believed he was hiding. The aim of this rollout was to obtain DNA to provide evidence that the bin Laden family was present. The false rollout was so carefully devised that the project was arranged to begin in the poorer part of the region to achieve greater authenticity. There was a logic I could understand.

Conspiracy theories are here to stay: Donald Trump is the Republican Party’s presumptive nominee for the 2024 US election, and Kate Middleton’s recent absence had been obsessing the internet. In this context, Day One’s conspiracy theorist couldn’t remain a monster. Instead, he’s an ordinary man, isolated and unlucky and seeking a community he can call his own. It makes for a much more interesting novel, and a much more frightening story. After all, he could be me; he could be you.

Abigail Dean’s Day debut, Girl A, was a Sunday Times bestseller. Her second novel, Day One, will be published by HarperCollins Australia on April 3.

It is our new Book of the Month, which means you can get it for 30% off the RRP at Booktopia with the code DAYONE. T&Cs: Ends 30-Apr-2024. Only on ISBN 9780008389277. Not with any other offer.

Come share your fave conspiracy theories, or better still your fave books, at the Sunday Book Club group on Facebook.