Warriors of the wards: Stories from the NSW Covid frontline

Every day for more than two years, frontline health personnel have faced the impact of Covid with 24-hour shifts, sudden deaths and medical unknowns. Today, these heroic workers reveal the heartbreak and triumphs from the hospital wards.

NSW Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For two years they have been on the frontline, digging in against the waves of frustration, fear, anger, illness and death.

They have been spat on, abused and challenged to use alternative medicine that doesn’t even work. And it has started again with Omicron.

Hospitalisations and intensive care admissions have tripled in just two weeks. They are our healthcare workers, those who calmly bear the frustrations of those who have waited too long for test, missed planes or had to cancel plans.

They have showed up to work every day, donning their armour – masks, eye shields, gloves and scrubs – sidelining their leave, putting in overtime, dealing with sadness, fear and anger.

They pushed beyond the fatigue, and even their own fears, to hold the hands of the over 600 who have died, helped thousands survive and celebrated when the sickest got to go home.

They are the Covid heroes in our health system, the ones we hope we never meet, but we salute you. There are thousands of them but here are the stories from the frontline of just a few.

Dr Zinta Harrington

Head of Respiratory Medicine at Liverpool Hospital

In early 2021, Dr Zinta Harrington, Head of Respiratory Medicine at Liverpool Hospital had watched the chaos play out in hospitals in New York and Italy and feared what would come when Delta hit Sydney.

“For a year and a half I had been watching the epidemic overseas and marvelling how the hospitals coped with large numbers of patients and wondering how on earth am I going to deliver that in Liverpool?” Dr Harrington said.

In the middle of the year she got to find out. Liverpool Hospital became the epicentre of the South Western Sydney Delta Covid outbreak.

It was the largest hospital dealing with a seemingly never-ending stream of positive patients, and then there was an outbreak within the hospital that claimed the lives of a dozen patients who acquired their infection on the wards.

“I learnt over July, September, October how you do it, so the first five weeks were difficult, the first time we had to open a full ward, first time we had to open a ward without negative pressure, first time we had non respiratory doctors looking after Covid patients, the first time we looked after such severe patients, but by September we were a well-oiled machine,” the 52-year-old mother of three said.

“In the beginning when we were learning how to do things it was exciting and exhausting and challenging.

“Although she was vaccinated, it was clear staff had caught Covid on the wards. She had two lives, one as a doctor on the front line, and one as a mother.

“In July, when it was all just starting, I realised I would be looking after lots of patients and I had unvaccinated kids at home.

“There was a time I pulled the car over and I was crying on my way home thinking I might put my kids at risk. That was the only time I felt emotionally overwhelmed.

I had a 19-year-old who still was not eligible for a vaccine then and a 14-year-old and an 11- year-old. I was thinking I’m at risk of bringing this home to my own kids and they don’t have say in it.”

It made Dr Harrington all the more careful.

“As the months went on we realised we were very good at not bringing it home,” she said.

“We had seven Covid wards plus the ICU and we had plans for the eighth and ninth. We had 160 patients at a time.”

Then Liverpool hospital became the centre of a hospital based outbreak.

“There were worst moments, not worst days. The worst moment for us was when there was an outbreak of Covid in the aged care ward,” Dr Harrington said.

“That was devastating and undeniably very bad. That led to a whole period of significant difficulty with very sick elderly patients with family that could not visit, it was terrible.

“Some of the worst things we experienced were people dying alone without family members being there to touch them and speak with them.”

Faced with death almost daily, Dr Harrington had to also confront denial and misinformation in other patients.

“It was more disheartening to see people who refused to be vaccinated or abusive because they did not believe in the disease and were requesting bogus medicine.

“It was very distressing and leads to a lack of trust both ways and the families don’t see things in the same ways. I don’t know how to explain it, just a different belief set and they can’t understand we were so committed to one set of beliefs.

“Most who were sick, after they recovered, they wanted to be vaccinated, but there were those who refused to acknowledge they even had Covid.”

After the Delta wave passed, the hospital returned to a brief period of normality.

“The best moment was when the visitors came back into the hospital, we could let them in again. When we stopped being a fortress and we started seeing real family members visiting and I didn’t realise how important that was to the whole functioning of our system. When you don’t have them you realise what is lost by not having them.”

Omicron has shut the doors to visitors again.

“We’ve turned the corner again, the numbers were steady and now they are going up again, but we are ready.”

Melissa Wakefield, 36

Liverpool Hospital Emergency Department nurse manager

While the wards filled with the sick during the darkest days of Delta, the emergency department was like a war zone.

Liverpool Hospital Emergency Department nurse manager Melissa Wakefield had never experienced anything like it.

“It was, in one word, intimidating. We knew what we were up against with Covid in general, we just didn’t know about this new Delta strain and how unwell the patients would be,” Ms Wakefield said.

“At the peak, the last week in September, it was chaotic, there were positive patients everywhere and that last week we saw 332 Covid patients in the ED, in one week. The worst day was that day we had 70 positive patients arrive, just one after another, and we’ve only got 65 treatment spaces in our ED, we have four isolation rooms.

“The one thing that was going to get us through was to have consistent staffing and not have anyone off quarantining in isolation, but absolutely that happened across all of our disciplines in the ED, we had a lot of staff off on quarantine leave.”

The idea that Covid was a disease of the elderly and frail was quickly proven wrong in the ED.

“We had sick, young 20, 30 year olds we were intubating and getting them up to intensive care. Compared to the original Covid strain in 2020, it was different, patients were sicker and we were seeing syndromes we have never heard of and we were intubating otherwise well people, they couldn’t breathe and they needed support to keep them alive, it was really scary.”

As the wards filled with Covid victims, triaging all other types of emergency patients, which did not stop just because of Covid, added another layer of complexity.

“As the biggest facility in South West Sydney we worked closely with our peers (in) Campbelltown and Bankstown (hospitals), and created pathways for non Covid patients so we were transferring our surgical patients over to Bankstown,” she said.

“We also formed a good relationship with Wollongong Hospital and developed a pathway with our Covid patients because our hospital was so overwhelmed with Covid. They reached out to us and offered help so in September we were assessing patients in the ambulance and redirecting to Wollongong.

“There were days when I felt we just couldn’t keep up but as ED clinicians we are highly resilient we work for each other and the patients.

“We were all in it together. At one stage we had doctors and nurses in the ambulance bay assessing patients to get them to Campbelltown or Wollongong.”

Amid all that, there was the abuse.

“There was verbal abuse absolutely and we had some staff that were spat on and we contacted the police for that. It did happen and it will continue to happen being an emergency department.”

On top of the stress at work, she too feared she may infect her family. The hospital had strict donning and doffing (putting on and taking off PPE) before leaving the hospital, but Ms Wakefield had her own plans in place at home.

“I have three children and it always in the back of my mind I could infect them, but my husband and I had a very solid plan from the start as to how we would manage things,” she said.

“When I came home from shift, I would not allow anyone to touch me, I’d go straight into the shower, wash my clothes and then I would go down and hug my kids and kiss my husband. It sounds silly but it made me feel secure not transmitting home to the kids.

“We’re definitely preparing for another wave. In the ED we are starting to see more. I would assume we will continue to see these waves until we get full compliance with vaccination.”

Dr Tim West, 40

Clinical immunologist at Campbelltown Hospital

Dr Tim West, clinical immunologist at Campbelltown Hospital, treated the sickest of Covid patients, many with sad outcomes.

“Over the course of the pandemic we had just under 1000 patients admitted. Over that four month period and at the peak, we had about 110 patients on the ward, and ICU between 10 and 15, there were so many in ICU we were shipping them out to other places because we couldn’t handle all the ones that needed ICU support,” Dr West said.

“It felt like you were in a movie, the hospital was deathly quiet in non-Covid areas because people stopped coming in. The Covid wards themselves had a really eerie feeling at times. There was sheeting put around each four bedded bay with zips up and down so the air from the Covid patients would not come out to where the doctors and nurses were.

“Everyone was wearing all the protective equipment and looked like they are out of a pandemic movie.

“It is very hard to convey just how sick Covid patients are. Physically, it is very scary to not be able to breathe and that sensation over hours is actually terrifying.

“I had a pregnant patient under my care who was unvaccinated. She was quite far into the pregnancy, in the second trimester and we were trying to give her the drugs that were safe in pregnancy but she miscarried and to have to go through that horrible experience without her family and without her partner and it was just really difficult.

“Covid is bad for pregnancy and women have been scared to get vaccinated but I’ve seen first-hand what happens when pregnant vaccinated women get Covid and the consequences can include miscarriage and that woman went to intensive care and was very unwell.”

That tragedy, and an entire unvaccinated family who had Covid, stays with Dr West.

“There were six members from the same family who were all admitted in a 24-hour period, one had died at home of Covid and the family did CPR but when the ambulance arrived he couldn’t be revived. there were six other family members brought from that same house in a 24 hour period and one of them went on to die,” he recalls.

“I spent a lot of time with the family and I asked them why they hadn’t been vaccinated and the truth is they were uncertain and they had seen things on the internet and they were more scared of the vaccine than of Covid. It is absolutely tragic, to have a disease that is so preventable play out I front of you, we knew we were the last line of defence.”

Like most medical staff, he too took extra measures to ensure his husband was not affected.

“I did fear taking it home, I was vaccinated but early on … I’d take off my clothes at the door and go straight to the shower, we could shower at work but often there was a queue, but absolutely I did fear for him.

“We had one doctor whose wife asked him to sleep in the shed when he was working on the Covid ward and he did that, he slept in the shed and showed up to work every day.

“These are historic times, there is something of a call to arms in this and we will think about this forever, I just hope we are through the worst and all of us can’t help but look at Omicron and just wonder what has been coming. When the next wave arrives, we’ll be ready.”

Alisa Berberovic, 24

Campbelltown Hospital nurse

Working alongside Dr West at Campbelltown Hospital was nurse Alisa Berberovic whose surgical ward was turned into a Covid ward.

“We had to upskill very quickly and Covid nursing was something we had never done before. We were a surgical ward so we had to go from that to respiratory. It was overwhelming,” she said.

“We had a few people that were there for a month and we could not wean them off oxygen and they were my age who were otherwise fit and healthy. It wasn’t just old people, it was everyone.”

As a nurse of just three years, the reality of the pandemic hit home very quickly.

“We saw so much death and we saw so many scared faces and every day was as difficult as the next, I can’t pinpoint one day as the worse,” she said.

“We were losing people every few days, it was difficult just seeing people deteriorate so quickly. Normally on a surgical ward, we can see it coming, but with Covid, it would be within a day and we wouldn’t expect them to deteriorate so quickly.

“At one point we couldn’t see the end of the tunnel, we couldn’t see light at the end of the tunnel because it kept going up and up and up and we were doing our very best at work, almost to no avail.

“People don’t understand, we had a lot of people say to us ‘I didn’t believe in it, I didn’t think it was this bad’ and here they are sitting in front of us not being able to breathe, it was a very common occurrence for people. They could not believe they did not believe it at first, they didn’t understand how serious it could get.

“It has been challenging to say the least. My family lived 30 minutes away, I live alone and I couldn’t see my family so it was hard to get support. It was pretty much work and sleep.”

Samantha Jane John, 44

St Vincent’s Hospital nurse

Samantha Jane John, like thousands, upskilled to deal with the surge. She was the nurse unit manager of a neurology ward which had to adapt to a Covid ward.

“It was challenging. We had to learn a new specialty and we had to lead people into a big practice change and learn the personal protective equipment (PPE) protocols and respiratory nursing,” she said.

Putting on and taking off the PPE became a strictly monitored protocol that needed to be supervised.

“We had to be extremely careful because a PPE breach increases the risk of transmission. So it was not only important to put the PPE on correctly, especially the n95 masks, but what was more important was the specific sequence that had to be followed when you took the PPE off, and that had to be supervised each time so it was done in the correct sequence.

“Unless you’ve had Covid or been directly involved, people do not have a sense of what it is really like. The patients were quite surprised by how unwell they felt and I think a lot struggled with the fact they were so isolated and could not have any visitors, so they really struggled without seeing their loved ones. They really relied on the nurses for that human contact and we were in full PPE so you never got to see our faces. That was also challenging.

“September was the worst month, it was so bizarre, it has been hard to get my head around what we went through, I feel like it was July and then we were spat out in November, it’s a bit of a blur.

“We started off with two Covid patients and then we had 34, the maximum we could fit on our ward, it just steadily rose and rose.

“We did have a few deaths on the ward and the biggest struggle with the nurses was trying to be there for the patient knowing they could not have any relatives there. We did facilitate some visitors under very strict supervision, but in full PPE they still couldn’t touch their loved ones, had masks on, it was heartbreaking to watch.”

There was also the ever-present danger of catching Covid on the job. Other staff in other hospitals had.

“I had to think about keeping myself safe at work in order to keep my family safe. I have two teenagers, and I was concerned I could bring it home but we were all fully vaccinated. I knew we had extremely strict PPE protocol and procedures so I did feel quite safe at work,” she said.

“I kept my spirits up with humour and I ate a lot of chocolate.”

Dr Mark Nicholls, 59

Intensive Care Unit at St Vincent’s Hospital

Dr Mark Nicholls was on the frontline during the 2020 Ruby Princess outbreak, but Delta was something else.

“I’ve never seen a sicker cohort of patients in my life, even those who got extremely sick and survived were very injured by it, and some were unable to survive,” he said.

“That was extremely sad when that situation arose, we did our best to facilitate family visiting within the rules we had, some patients were non-infectious with Covid and we’d move them out of ICU so we could enable family to visit.

“Most were unvaccinated in the intensive care unit. The patients we were looking after were so sick and so unwell with Covid and they were not vaccinated and when you spoke with their family, the family had regrets.

“It was the misinformation and miscommunication that meant people who would have been vaccinated earlier ended up in the intensive care unit, so I found that quite distressing, hearing that they would have been vaccinated but delayed because of misinformation. “

Amid the sadness and frustration, there were moments to celebrate.

“It was incredibly rewarding having patients who were extremely unwell recovering and each case that left the ICU we celebrated. We did have some of the best outcomes with Covid in the world.”

Like most of his colleagues, he also feared bringing the virus home so rented a small one bedroom unit near the hospital at his own cost.

“During the last surge I stayed away from my family, I lived by myself for six weeks. I was not alone in doing that, other doctors and nurses did the same. We spoke with family on the phone.”

What changed the situation dramatically was the vaccination rate.

“The vaccination rates were critical and they have changed everything. The dramatic decrease in the number of patients in hospital and in intensive care, we have to thank the community for the high vaccination rates and if the vaccination rates had not got as high as they did, it would have been a different situation,” he said.

“We are not out of this pandemic yet, we can’t relax.”

Natalie Shiel, 45

Acting director of nursing for the vaccination program, Sydney Local Health District

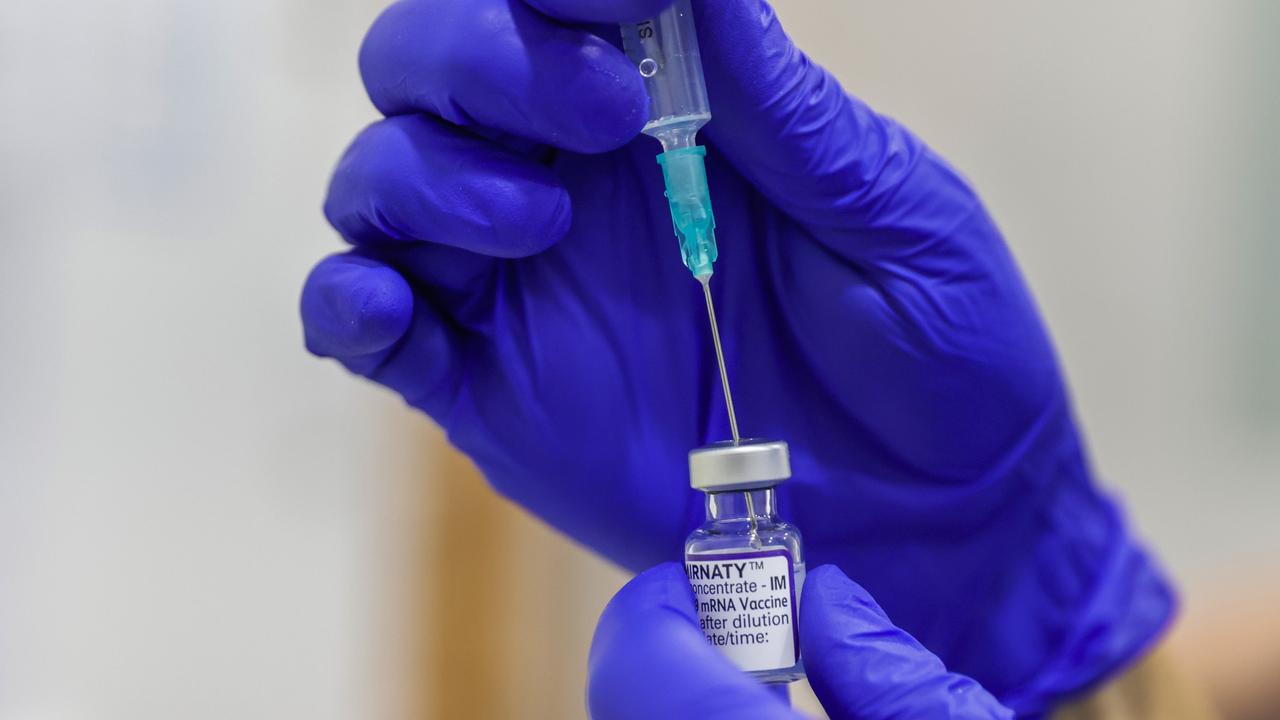

Natalie Shiel has co-ordinated more than 1.4 million jabs this year.

“I was based at Olympic Park since June and before that I was looking after our airport and flying squad teams. It’s been difficult at times, but overall it has been positive and we have made a difference to the outcome of Covid in NSW,” she said.

“We’ve had up to 300 nurses a day onsite at our peak just doing vaccinations at Olympic Park and we had staff out in our mobile vaccination clinics and little pop up clinics.

“There were times it was difficult, people were anxious and scared and there were some people who were difficult but we are good at managing those people and reassuring them and getting the right outcome for them. Our high vaccination rate has made us proud of the work we have done.”

Dr Rohan Beresford, 35

Infectious diseases physician at Concord Hospital

Dr Rohan Beresford helped manage outbreaks in residential aged care facilities as well as working in the Concord Hospital wards.

“Concord always took patients out of hotel quarantine, so the workload never dropped here. I think at the peak of Delta we switched from having one small Covid ward, to opening three Covid wards and an ICU,” he said.

“It was very confronting on the Covid ward, it is hard to describe how unwell the patients were. The wards were full and you’d walk around and every patient is on oxygen, a large number look and feel very unwell. Patients are taught to prone, to roll over to their front to oxygenate and we doubled our intensive care capacity because patients were becoming so unwell.

“One of my focuses has been working in aged care outbreaks and trying to minimise the impact of Covid-19 on our older residents. You get a call about a positive case in an aged care facility and then everything needs to swing into place extremely fast.

“I think my darkest day was when you really felt like you were trying to hold back a tide and seeing a lot of positive cases and seeing that rapid spread of the virus. It felt like you were never doing enough.

“The biggest outbreak was in Summer Hill and we had a large number of cases and that required evacuation of the facility to stop ongoing transmission. That ended up with residents being admitted to hospitals right around Sydney.”

With immediate family in Canberra, and a partner in a separate part of Sydney with concerning numbers, the long days at work became long lonely nights as well.

“For me it was work and sleep and work and sleep. And there have been times when I had not a day off for six weeks and most days were 16 hours. I have a very understanding partner.”

Another challenge was the parallel pandemic of misinformation on the wards.

“There have been a minority of those strongly anti-vax and did not believe in Covid and that became very confronting when someone was very unwell and needed a lot of intervention. We were working to provide health care but at the same time being challenged about their diagnosis and being told they want to seek treatments not recognised as effective.”

Got a news tip? Email weekendtele@news.com.au