Spanish flu pandemic: 102 years to the day Sydney queued for vaccine

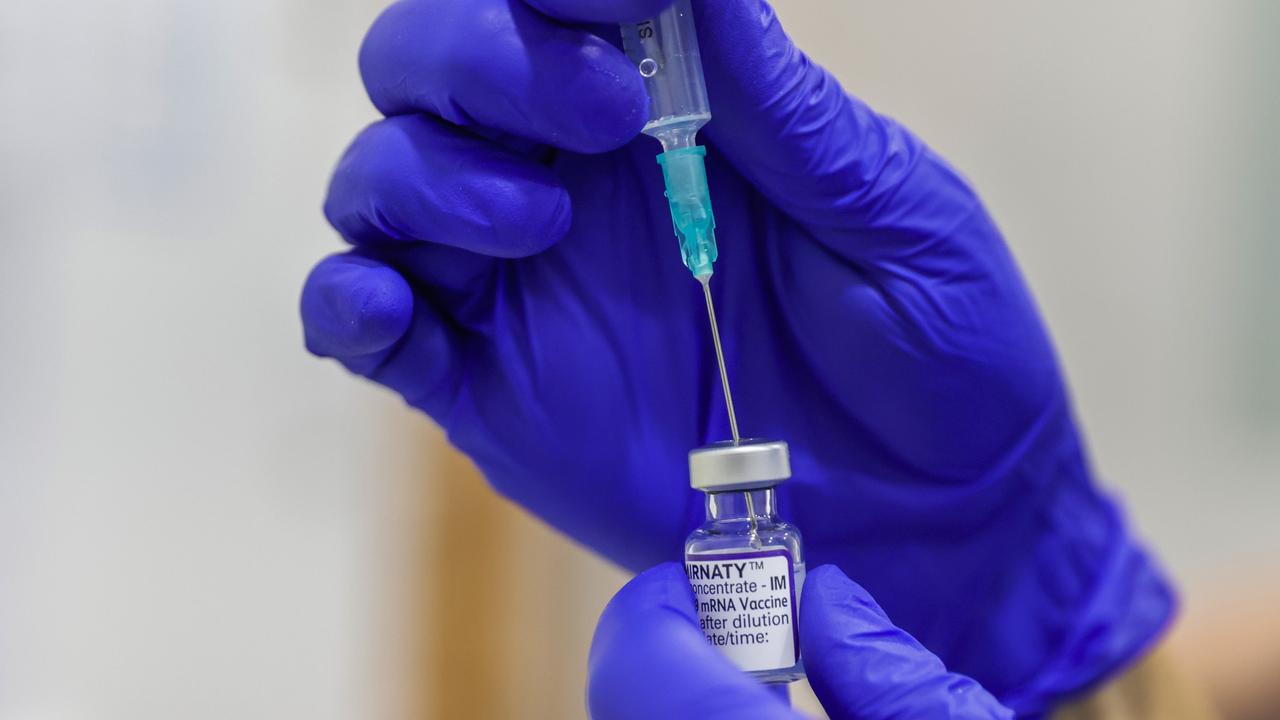

As the world today faces COVID vaccine shortages, exactly 102 years ago Sydneysiders began queuing in crowds for an experimental jab.

NSW Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The more things change, they stay the same. On January 29, exactly 102 years ago today, Sydneysiders were queuing up in great crowds – from the Sydney Town Hall to Hyde Park and suburban council chambers to get their experimental public flu jab against the deadly Spanish flu, or H1N1 influenza A, as it was later identified as.

Sydney factory and shop workers were encouraged to turn up en masse to get their shots, with glass syringes and needles so blunt that survivors later spoke about lifelong scars “the size of a florin”, or almost three centimetres and the same needle being used.

Women and children – but not those under six as they weren’t entitled to a vaccine – crowded the suburban depots and queues became so bad that several people collapsed at a Rockdale depot that night.

Unlike today, those over 65 were not eligible for the Aussie-made inoculation – with authorities determining the killer influenza was far more deadly for adults in their 20s to 40s.

With the flu leaking out of quarantine stations, carried by returning Great War soldiers, the NSW Government made sudden orders on 28 January 1919 to immediately shut libraries, theatres, churches, places of indoor entertainment and public halls.

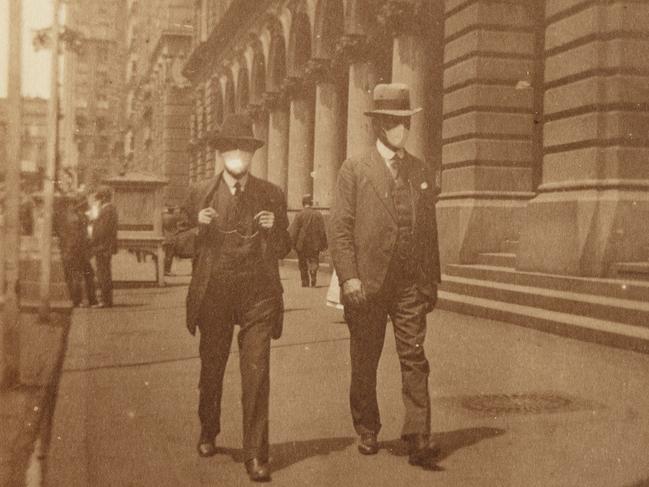

Sydney’s schools – which just like today had only returned from the Christmas holidays – were also closed and masks were made compulsory a few days later – “Mask Day” on February 3.

The papers of the day reported many cases of rebellion, especially among outdoor workers having trouble breathing in the summer heat and people wanting a sneaky smoke.

Women began sewing bees to make masks from muslin and gauze. Railways began asking people to fill out travel forms, in a very early version of QR codes.

“The events from 101 years ago are startlingly similar,” says NSW State Library curator Elise Edmonds.

“We were having the same challenges, there was quarantine, social distancing, a lot of city workers went part time, border closures, there were compulsory masks and public health advice about catching transport.” She’s just helped curate an exhibition at the library, Pandemic, which includes rare memorabilia about how the deadly Spanish flu hit ordinary citizens.

“Obviously the technology is different now, so more people can work from home, but it is remarkable how many similarities there are,” she said.

Just like today, health authorities sent out messages encouraging people to cover up sneezing or coughing on trains, as well as suggesting people buy things over the phone or use a telegram for a delivery to avoid visiting the shops.

And just like today, Australian health authorities had the benefit of using quarantine to buy time and watch the pandemic’s progress overseas. This enabled them to work on their own pioneering vaccine, where a total of three million doses were created by both the CSL labs and NSW Health.

“Australia was fortunate that the flu arrived on our shores after other countries had already experienced the pandemic and was able to apply lessons they had learned,” Newcastle University’s Associate Professor Nancy Cushing says.

“Australia was unique in having an official national campaign of inoculation which started before the flu arrived.”

Called “inoculations”, the crude vaccines were made from a mixture of chemically killed common respiratory bacteria such as streptococcus pneumoniae – and rushed into production just before the outbreak at the start of 1919.

“We are endeavouring to inoculate 1,750,000 people as rapidly as possible,” the Micro-Biological Department of the Board of Health boss Dr Cleland told newspapers at the time.

More than 1260 public inoculation depots were set up across Sydney and 819,000 inoculations performed in just six months.

It is believed the new vaccine worked against the secondary bacterial infection, such as staph, which invaded the lungs after people caught the killer respiratory flu.

As the months wore on, almost 40 per cent of Sydney’s population were infected, with 15,000 dying – a huge number for the small population at the time with many young adults in their prime – and 5000 children lost one or both parents.

Helen Carter from the Balmain Association said the effect on some families had been particularly terrible, citing the prominent Franki family of the historic Montrose home, where two grown sons died following the earlier death of a son in the war.

“In Balmain families devastated by the deaths of their sons in The Great War were confronted with fighting their own battle at home the influenza epidemic,” she said.

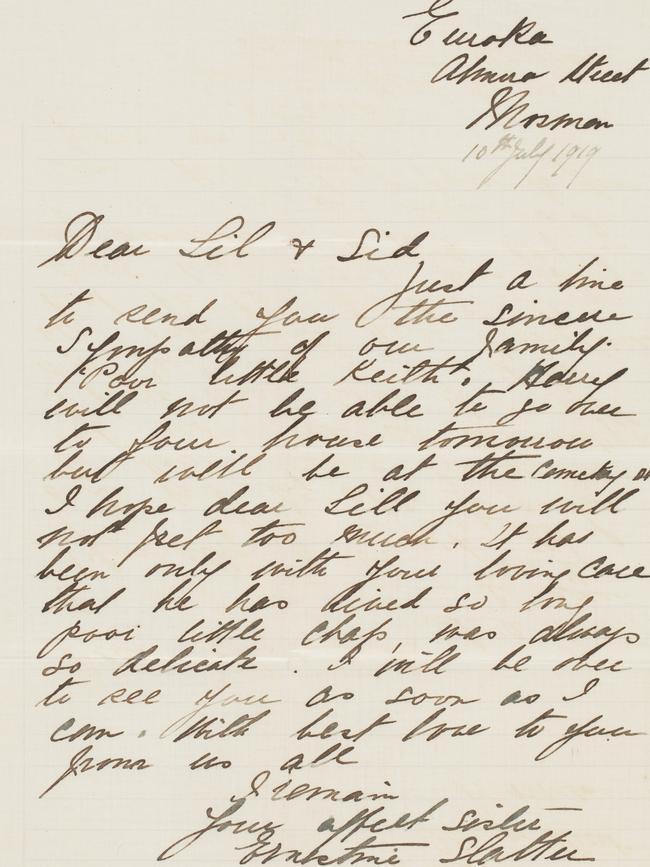

Another tragic case was 14-year-old Balmain boy Keith Sydney Butler, who died at the height of the epidemic.

Just like now, where state border closures have deprived grieving families of the ability to attend funerals, the same happened with his family, as revealed in the NSW State Library’s exhibition of his condolence cards.

“There are almost no memorials to those who died in 1919, so the condolence letters and cards sent to Keith’s parents and older sister are incredibly valuable and so moving – they show the grief and sadness felt by family unable to attend Keith’s funeral and had to mourn from afar,” Ms Edmonds said.

Family friend Dolly Parry wrote on 16 July 1919: “I am so grieved for you … Poor little kid! I have been … wondering how things were with you and if you were escaping the epidemic.”

Clare Stretton, whose father was Keith’s cousin, donated the letters to the library several years ago.

“I was very moved by the correspondence, there was an enormous amount,” she said. “I knew his sister Gwen well, and yet she never said anything about it.”

Eventually nearly a quarter of NSW residents got the flu jab and while later historians think it did not necessarily prevent infection, they do credit the vaccine with resulting in Australians suffering a milder, less fatal sickness and bringing down the death toll, which was less per capita than in New Zealand.

“The widespread inoculation program showed that the vaccine was not effective in preventing the flu, although did help to ward off the secondary bacterial infections such as pneumonia which proved lethal in many cases,” Assoc Professor Cushing said.