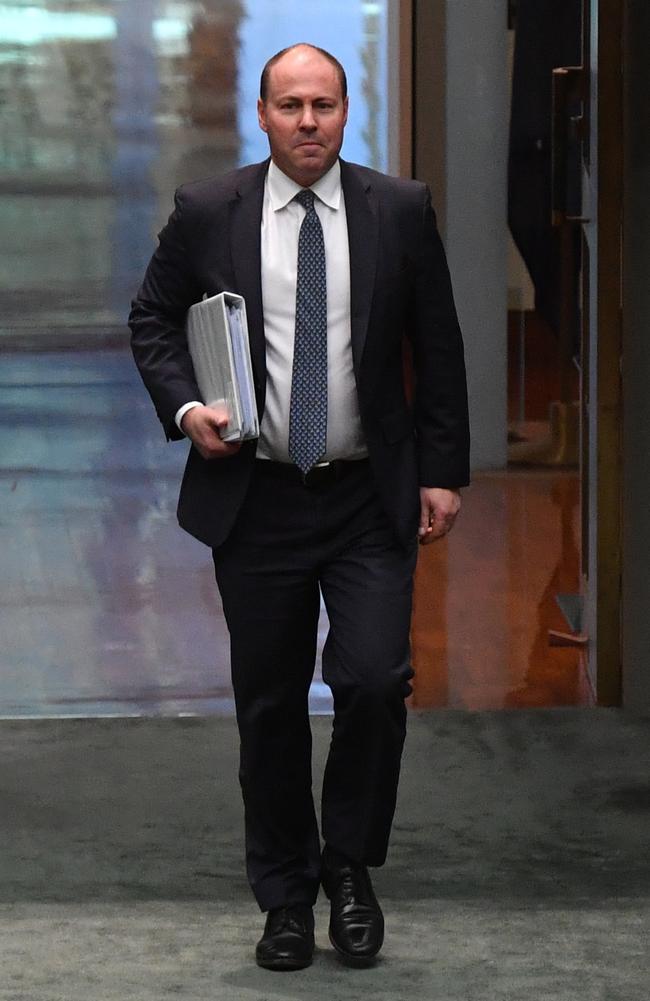

Josh Frydenberg: Making tough choices in tough times

Australian Treasurer Josh Frydenberg is taking nothing for granted as he strives to navigate ways to further stimulate the national economy, writes Clare Armstrong.

NSW Coronavirus News

Don't miss out on the headlines from NSW Coronavirus News. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Treasurer tests negative for COVID-19

- Let’s get down to work on recovery mission

- Retirees ‘expect more than just a token drop’ in the deeming rate

There’s a neatly folded handkerchief sitting on Treasurer Josh Frydenberg’s desk, a gift from a constituent after he committed a coronavirus cardinal sin — coughing into his hands.

A year ago Mr Frydenberg believed May 12, 2020, would be the day he delivered the first federal government budget in surplus in more than a decade.

Instead it’s the day he stood before a special socially-distanced sitting of parliament to try to help Australia make sense of the “deepest of holes” the COVID-19 pandemic had caused in the economy.

In a cruel twist of fate, the Treasurer temporarily succumbed to a severe coughing fit mid-speech.

“There’s a letter sitting there from a lady who sent me a handkerchief because she saw me coughing, and she thought I was coughing into my hand and I should know not to do that,” he says.

Following the coughing episode, Mr Frydenberg immediately sought a precautionary COVID-19 test, returning a negative result.

He’s one of more than 1.3 million Australians to have received such as result since January.

It’s this extremely effective testing regimen that has in part helped to flatten the coronavirus curve in Australia which has allowed Mr Frydenberg to switch his focus to getting the economy off life support.

SEVERE IMPACT

In the early days of the coronavirus outbreak in Australia on February 21 Mr Frydenberg travelled to Saudi Arabia for a G20 meeting.

It was at this two-day gathering of global finance leaders that the Treasurer says he first began to get a sense of the economic outlook awaiting Australia should the pandemic take hold.

“The Singaporean minister talked about what was occurring in his country and how they were going to run a budget deficit for the first time in a long time,” he says.

“It sort of gave me pause to think about the pandemic playing out on the economy here and having a severe impact.”

Not long after Mr Frydenberg returned from overseas, he says “things got worse”.

“Once the health restrictions were put in place, that was obviously starting to impact the economy,” he says.

“You had the panic buying, fights over toilet paper. We closed the borders, but no one really had an expectation that it would lead to this global pandemic playing out the way it has.”

Consumer and investor confidence plummeted as businesses shut, large gatherings were banned and non-essential movement ceased.

The government pivoted to referring to the COVID-19 pandemic as being “twin crises” — one on the health front, and the other economic.

Mr Frydenberg says the three tranches of economic support announced through March was “effectively like doing three budgets in three weeks”.

“I remember I brought enough clothes to Canberra for four or five days, and ended up staying for 15,” he says.

JOBS MARKET

When he has been able to get home to his Kooyong electorate in Melbourne’s inner east, Mr Frydenberg has been focused on the “impact” the coronavirus pandemic has had on his two children, aged three and five.

“I’ve spent a lot of time with my kids at home, either on the weekends or in the times I’ve been able to be at home,” he says.

“My daughter was asked what does she hope for most and she said, ‘that the virus goes away’ … and she’s just five.

“So that must be a thought that’s running through every kid’s mind in this country.”

Mr Frydenberg says he’s particularly worried about what COVID-19 means for Year 12 and university students about to graduate.

“I’m worried the job market, for not just people who are in jobs today, but what about those kids coming out of uni or coming out of school who are going straight into the jobs market,” he says.

“What’s that going to look like for them? There’s some data to indicate there’s going to be a harder jobs market.”

Mr Frydenberg says he’s “thinking very much about the human side of it”.

“The young people who are going to think about this for some time, the people who live at home who’ve been pretty lonely,” he says.

The Treasurer needs no reminder of the enormity of the health challenge and potential for devastation should Australia suffer a second wave of COVID-19, revealing his own family came close to tragedy in the early days of the pandemic.

“I had a cousin who got the virus and ended up in ICU in Melbourne,” he says.

“He had been in the United Kingdom and contracted it there and so did his wife. He came back to Australia … and he ended up in the hospital in ICU and they thought he might die.

“He is a very close relative, so that brings it home.”

While health officials were conservatively forecasting at least 50,000 Australians would die from COVID-19 by August, Treasury bureaucrats rushed to keep up with measures to combat the potential economic impact.

“Obviously as a treasurer your instinct is not to spend too much money, and so recognising that we really needed to dig deep to spend a record amount of money during the crisis was critical,” Mr Frydenberg says.

“To go from being on track to surplus with economic discipline to facing a global pandemic, to which you need to respond with record spending, is a 180-degree turn.

“I remember when we did the first package, which was $17.6 billion, people were saying ‘oh that’s great, that’s dealt with it, the economy’s going to bounce back’.

“Then the second package was even bigger again (about) $66 billion, and then the third package was the JobKeeper.”

SUBSIDY

The day Mr Frydenberg stood next to Prime Minister Scott Morrison to announce the then-$130 billion JobKeeper program the mood was sombre.

For weeks the government had resisted the idea of a “wage subsidy,” criticising the scaled models being introduced in places like New Zealand and the UK, where furloughed workers would be paid based on a percentage of their normal income.

The Morrison government did not want people who normally earned more money to get more taxpayer cash than those who had been on a lower income.

But in late March, as thousands of Australians queued outside Centrelink offices — recalling scenes from the Great Depression — it became clear the severe economic impact of shutting dozens of industries could not be mitigated by the JobSeeker welfare payment.

Maintaining the connection between employees and businesses was the new priority, thus the flat-rate $1500-a-fortnight wage subsidy was decided.

The historic $130 billion program was expected to keep about six million full, part time and long-term casual workers on their employers’ books until the COVID-19 curve was flattened and businesses could reopen.

However, less than two months later the government faced the largest budgetary bungle in Australia’s history when officials revised down the cost of the JobKeeper program by $60 billion. But that’s not how Mr Frydenberg sees it.

“This is a revision from Treasury about the JobKeeper program because it’s based on us being more successful on the health front than we previously were,” he says.

Mr Frydenberg said at the time estimates for the JobKeeper package were made, the federal government “feared the worse”.

“Treasury had advised me there was a chance we could go into lockdown and the economic implications of that would be very severe,” he says.

“They talked potentially of a 24 per cent fall in GDP in that June quarter.”

When JobKeeper was announced on March 30, the rate of coronavirus cases in Australia was increasing by about 20 per cent a day.

By comparison, for the last 40 days Australia has successfully kept the daily rate below an increase of 0.5 per cent.

“In the week leading up (to JobKeeper) … everyone was really worried about the deepest of holes that was being created in the economy,” Mr Frydenberg says.

“So it was quite understandable what Treasury did in terms of forecasting a worst-case scenario.

“But the other thing that happened, coincidentally, was when the Tax Office collated the data … some of the businesses had incorrectly filled the forms.

“So rather than being 3.5 million people covered it was 6.5 million and because that was close to where Treasury had originally forecast … there was a degree (of) confirmation bias.”

most proud

But Mr Frydenberg isn’t looking to apportion blame, insisting forecasting the cost of such an enormous program in the middle of a pandemic “is very hard”.

“No one was underpaid, no one was overpaid,” he says.

“We’re in a position where we’re raising $60 billion less than we thought we might have to … (and) every dollar we spend, is a dollar we borrow during this pandemic.”

Mr Frydenberg says the now-$70 billion JobKeeper program is among the policy responses during the pandemic he’s most proud of.

“I think that was really important in terms of giving confidence, so in the week after it was announced consumer confidence had its biggest jump on record,” he says.

“I’m (also) really pleased that we were able to reach an agreement with the banks to get them to defer interest for six months. You’re talking over $220 billion worth of loans … that’s a huge relief to businesses."

This week Mr Frydenberg spoke with the head of the International Monetary Fund Kristalina Georgieva, who warned the world was not “out of the woods”.

“Her prognosis was the global economy is continuing to struggle, and Australia is in a much better position,” he says.

With that position comes challenges, but also a historic opportunity for reform not lost on Mr Frydenberg.

“We’ve obviously got big questions to work through in terms of the JobKeeper and the JobSeeker programs, given that they’re legislated for six months,” he says.

“But the budget is the time for those such policies, in terms of the bigger reform agenda to be announced, but we’re certainly looking at our options.”