Wuhan COVID mission: Australian scientist explains what happens next

The Australian scientist who was part of the WHO’s international mission to Wuhan, has explained what must happen now.

Coronavirus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Coronavirus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Australian scientist who was part of the World Health Organisation’s international mission to Wuhan, has explained what must happen next after their report was published globally.

Dominic Dwyer wrote in The Conversation the key focus of needs to be on looking into what happened before people realised there was a clinical problem in December 2019, not just in China but in other countries with early cases, such as Italy and Iran.

“This would give us a more complete picture of whether SARS-CoV-2 was circulating earlier than December 2019,” he said.

“For instance, if we just focus on China for now, we know there were influenza-like respiratory illnesses in Wuhan in late 2019.

“In fact, we looked at data from more than 76,000 cases for the WHO report, to see whether these could have been what we now call COVID-19.

“But work is already under way to reanalyse those data using different techniques, to see if we’ve missed any earlier cases.”

He said talks are also under way to see if blood donations in China in 2019 can be analysed to see if they contain antibodies to SARS-CoV-2.

“Then there’s what we can learn from molecular epidemiology (the genetic makeup of the virus and its spread),” he wrote.

“For instance, if we find a lot of variation in the genetic sequence of early samples of SARS-CoV-2, this tells us there had already been transmission for some time.

“That’s because the virus doesn’t mutate unless it infects and transmits. We can use modelling to say what might have happened up to three or more weeks beforehand.”

But he said this data needs to be linked to actual clinical data.

“Until now those data have largely been separate, with the molecular data held in research or university laboratories and the patient data held elsewhere. We need to make those connections to tell us which infections were related, and how far back in time they go,” he said.

He also added they haven’t looked at biological samples sitting in laboratories around the world.

“So we have to do a bit of detective work to locate them and analyse them to understand the pattern of disease and to help sort out the origin. There is no central database of samples and what antibodies or genetic material they might contain,” he said.

One other point he made was for the need to have “ongoing sampling of animals and the environment for signs of SARS-CoV-2 or related viruses”.

“Can we find the virus in an intermediary animal, and if so, what type of animal and where? Again, these are difficult studies to set up,” he said.

THE WUHAN MISSION - YOUR QUESTIONS ANSWERED

Who authorised the report and what is it about?

The report was commissioned by the World Health Organisation, a UN agency, to set out the results of the fact-finding mission by an international team of experts.

The goal of the report is to lay out the findings around the origins of COVID-19 and work out how it jumped from animals to humans and started the coronavirus pandemic.

Who wrote the report and what is it based on?

The report was drafted by a team of international experts appointed by the World Health Organisation and their Chinese counterparts.

This team of international scientific and medical experts were chosen by the WHO and finalised in consultation with Beijing.

The approximately 400-page document is based on research gathered from field visits, interviews, and records from requested sources and at requested sites by the WHO team. These include patients, people in the community, staff at institutes, hospitals and the wet market linked to the initial outbreaks of coronavirus in Wuhan.

Who were the experts and was there an Australian on the team?

Professor Dominic Dwyer represented Australia. He is a medical virologist and Director of the Centre for Infectious Diseases and Microbiology Laboratory Services at Westmead Hospital in Sydney.

Prof Dwyer trained as a microbiologist then studied the HIV/AIDS virus at the Institut Pasteur in Paris. He advises the Australian government on pandemic preparedness and response, particularly bird flu and worked with the WHO during the SARS outbreak in Beijing.

In an article Prof Dwyer wrote for the ABC, he said the mission was a joint exercise between the WHO and the Chinese health commission, with 17 Chinese and 10 international experts, plus seven other experts and support staff from various agencies.

International experts included:

John Watson, UK, Infectious diseases epidemiologist

Peter Daszak, UK/US, Zoologist and virus hunter

Marion Koopmans, Netherlands, Virologist

Farag El Moubasher, Qatar, Infectious diseases expert

Hung Nguyen, Vietnam, Ecologist and zoonotic diseases

Thea Kølsen Fischer, Denmark, Professor in viral epidemics and infections

Peter Ben Embarek, Denmark, Food scientist

Fabian Leendertz, Germany, Virus hunter

Ken Maeda, Japan, Veterinary microbiologist

Vladimir Dedkov, Russia, Epidemiologist

When did they go to Wuhan and how long were they there?

The WHO team arrived in Wuhan on 14 January, 2021 to start its four-week investigation into the origins of the coronavirus pandemic.

The scientific probe came after months of negotiations between the WHO and Beijing, some delays, and a quarantine period.

What did the experts do in Wuhan?

The WHO investigators met with Chinese officials, scientists, health, medical, and agricultural experts, first responders to coronavirus outbreaks, and some of the first known COVID-19 patients.

In an attempt to establish the origins of the virus they analysed lab data, patient health records and samples in Wuhan and surrounding Hubei province from 2019 and looked for unusual spikes in influenza-type illnesses, severe respiratory infections, and deaths related to pneumonia.

They went on field trips to find clues that could trace which animals at the Wuhan ‘wet market’ may have carried the virus, and where those animals came from.

They also visited hospitals and laboratories including the Wuhan Institute of Virology and the Wuhan Center for Disease Control laboratory.

The scientists tried to find evidence for theories that the virus escaped or was released while it was being studied at the lab by virologists at the Wuhan Virology Institute, a high security biosafety lab that works with highly contagious pathogens.

Why focus on Wuhan?

COVID-19 was first detected in Wuhan in central China in late 2019 and is considered to be the original epicentre, if not origin of the coronavirus pandemic.

The majority of the early cases reported in December 2019 and January 2020 were directly linked to the Huanan Seafood Wholesale Market in Wuhan City, which sold seafood as well as live wild and farmed animal species.

It is believed that the market could have been the source of the outbreak or helped spread it.

What do we know from the trip to Wuhan?

The international team announced in a press conference on 9 February, 2021 that coronavirus “most likely” originated in animals before spreading to humans.

The experts dismissed theories that the disease had been leaked by a laboratory in Wuhan.

The initial findings of the investigation found no evidence of major COVID-19 outbreaks in Wuhan before December 2019.

However, expert Peter Ben Embarek said they did find evidence of wider coronavirus infections spreading beyond the Huanan Seafood Market that month.

Prof Dwyer, the Australian team member, said there was some evidence that coronavirus could have spread on contaminated fish and meat at Chinese markets, but that none of the animal products sampled after the market’s closure tested positive for SARS-CoV-2. He wrote in an article for the ABC that visiting the market showed how easily the virus may have spread there due to poor ventilation and drainage.

What did the report conclude?

The long-delayed report ranked four hypotheses in order of probability. They said the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes COVID-19 disease most probably jumped from bats to humans via an intermediary animal, judging a lab leak to be an “extremely unlikely” source.

But the document offered few firm conclusions. It said evidence suggested the COVID-19 outbreak may have begun several months before it was first detected in Wuhan in December 2019, and called for COVID antibody testing of samples in Wuhan blood banks from as far back as September that year.

They also said it remained unclear what role the Wuhan market had played in sparking or amplifying the initial outbreak, and presented no clear answer on how the virus first jumped to humans.

Dutch virologist and team member Marion Koopmans rejected the focus on the unanswered questions, stressing on Twitter that the experts had presented a huge amount of information.

“Not everything answered but surely a good start,” she said.

The experts worked to rank a number of hypotheses on the pandemic origins according to how likely they were.

They believe that the SARS-CoV-2 virus that causes the COVID-19 disease originally came from bats.

One theory examined was that the virus jumped directly from bats to humans. The final report determined that this scenario was “possible to likely”.

“Although the closest related viruses have been found in bats, the evolutionary distance between these bat viruses and SARS-CoV-2 is estimated to be several decades, suggesting a missing link,” the report said.

“The scenario, including introduction through an intermediary host, was considered to be likely to very likely,” it said.

The report did not however conclusively identify which animal first allowed the virus to jump to humans, but it named a number of candidates, including mink, pangolins, rabbits and ferret badgers.

A third hypothesis the experts examined was whether the virus may have been imported to Wuhan in frozen food, a favourite theory in Beijing, which has questioned the initial assumption the virus originated in China.

The report did not rule out transmission through frozen food, since the virus has been shown to survive on frozen food packages, and listed the theory as “possible”.

But while it said there was some evidence that people could be infected through handling contaminated frozen products, it was very unlikely that was how the virus was first introduced.

Finally, the report examined the idea of a lab leak from, for instance, the Wuhan Institute of Virology — a theory promoted by former US president Donald Trump’s administration.

It pointed to the fact that there was no record of any virus resembling SARS-CoV-2 in any laboratory before December 2019, and stressed high safety levels at the labs in Wuhan.

“A laboratory origin of the pandemic was considered to be extremely unlikely,” the report said.

Why was the Wuhan lab theory rejected by the WHO experts?

Peter Ben Embarek said at the 9 February press conference in Geneva that the team had conducted extensive discussions with staff at the Wuhan Institute of Virology, which is at the centre of the theories, and similar labs nearby.

He said a leak is unlikely because the virus was not known to scientists and virologists before December 2019, and therefore must have come from the wild.

But at the February press conference, Australia’s Prof Dwyer said that while the team didn’t see anything during its visit to suggest a lab accident, the conditions of the visit made it impossible to tell if one had happened.

“Now, whether we were shown everything? You can never know. The group wasn’t designed to go and do a forensic examination of lab practice,” said Prof Dwyer.

Will the world be satisfied with the report?

The WHO coronavirus probe appeared to have been shrouded in secrecy, interference and supervision from Chinese officials, casting pre-emptive doubt on the findings of the report.

Additionally, the WHO team of experts have favoured the two hypotheses (infected mammal or frozen food) that are the same theories promoted by the Chinese government.

Some speculators believe that those theories are being emphasised as a way of depoliticising the pandemic and absolving China of blame or lack of transparency.

“It was actually very complicated and very tense,” Prof Dwyer told the ABC of the visit. “There is certainly political pressure, and I think that pressure is actually more on the Chinese side than it is on us.”

But one of the experts, Peter Daszak, told The Associated Press, that team members had submitted a list of places and people to include in their investigation and that no objections had been raised by China.

“We were asked where we wanted to go. We gave our hosts a list … and you can see from where we’ve been, we’ve been to all the key places,” Mr Daszak said. “Every place we asked to see, everyone we wanted to meet. … So really good.”

During the investigation, China held daily press briefings. At one of those, Chinese Foreign Ministry spokesman Wang Wenbin said:

“It should be noted that virus traceability is a complex scientific issue, and we need to provide sufficient space for experts to conduct scientific research. China will continue to co-operate with WHO in an open, transparent and responsible manner, and make its contribution to better prevent future risks and protect the lives and health of people in all countries.”

But the 400-page report had been delayed, casting suspicion that it is being censored or undergoing an approval process by Beijing.

The experts involved said the delay is just the WHO fact checking and translating the document, according to Danish scientist Peter Ben Embarek.

“We are at the point where we are cleaning up the document to make sure all the experts are OK with the content,” he said at a press conference.

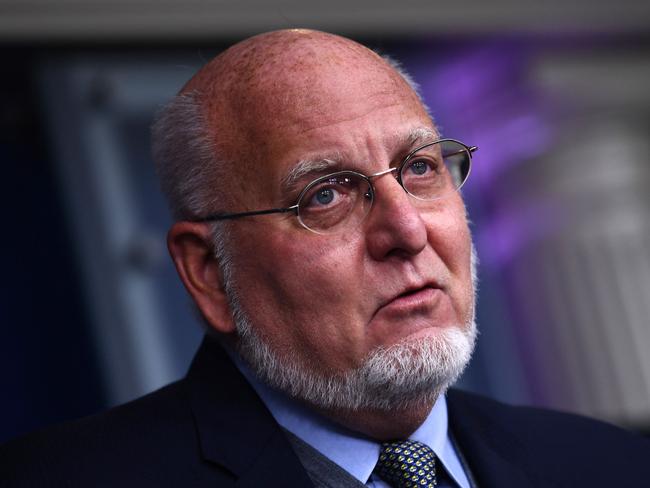

It comes as Robert Redfield, the former director of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention told CNN on 26 March, 2021, he believed coronavirus escaped from a laboratory in Wuhan, a theory that the WHO scientists have already dispelled while amplifying the animal-to-human transmission theory.

“I do not believe this somehow came from a bat to a human, and at that moment in time, the virus that came to the human became one of the most infectious viruses that we know in humanity for human-to-human transmission,” said Dr Redfield. “I am of the point of view that I still think the most likely etiology of this pathogen in Wuhan was from a laboratory, escaped.”

The United States, Japan, Canada, South Korea, Australia, Israel, Britain and seven other European countries issued a joint statement voicing concerns that the investigation “was significantly delayed and lacked access to complete, original data and samples”.Independent experts needed “full access to all pertinent human, animal, and environmental data, research, and personnel”, they said.

Will there be further investigations?

Based on the 9 February press briefing, which outlined the largely inconclusive findings of the Wuhan WHO probe, scientists say that the hunt for the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic must continue.

The WHO team has also said that investigations in Wuhan and Hubei province should continue, especially to track down the earliest cases, which could help researchers to understand the pandemic’s origins, which the report has been unable to conclusively pin down.

The WHO team also recommended broadening the search for the virus’s origin outside of China, as there have been reports of coronaviruses similar to SARS-CoV-2 being found in bats in Japan and southeast Asia.

In Geneva on Tuesday, WHO boss Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus said the probe into Wuhan’s virology labs had not gone far enough, adding that he was prepared to launch a fresh investigation.

“I do not believe that this assessment was extensive enough,” he told the UN health agency’s 194 member states, in a briefing on the COVID origins report.

“Further data and studies will be needed to reach more robust conclusions,” he said.

“Although the team has concluded that a laboratory leak is the least likely hypothesis, this requires further investigation, potentially with additional missions involving specialist experts, which I am ready to deploy.”

— With AFP wires

Originally published as Wuhan COVID mission: Australian scientist explains what happens next

Read related topics:Explainers