The world is now hooked on cheap money and budget deficits

The people who govern us - both the politicians and the central bankers - are making a universal one-way bet. Here’s why it’s disturbing and very dangerous.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The one big thing that investors and indeed everyone else have to understand is that the people who govern us — both the politicians and the central bankers — have, right around the world, committed to permanently rising share and property values.

I need to immediately add that does not mean that all shares and all property will always go up in value.

Individual share prices can and will fall — indeed, as we saw with Virgin, they can go all the way to zero. Individual property can fall as well, if more in relative terms to other property and almost never all the way to zero.

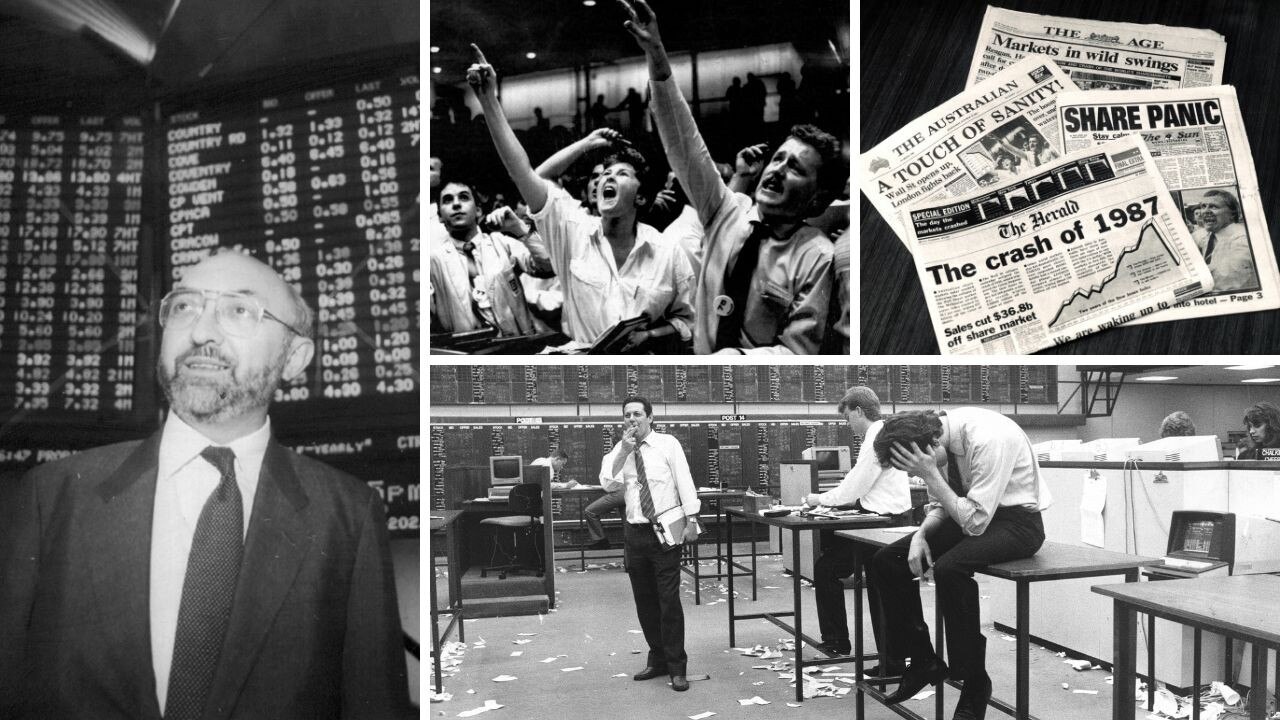

This also doesn’t mean we can’t get sudden across-the-board plunges — like we saw in February; like we saw with the Global Financial Crisis; and like indeed we saw in 1987.

The key point is what happened after those falls and most specifically the last two — the way share prices in particular but also property generally came straight back, precisely as a consequence of what central banks, most particularly the US Fed, and governments did and will keep doing.

Overnight Friday, Wall Street got back to its all-time February high. The tech sector — the Amazons, Apples, Googles and the like, captured in the Nasdaq — had already got there mid-year and it’s now a stunning 20 per cent higher than that earlier peak.

In very simple terms tech has had a spectacularly good virus. It’s ridden the global lockdown boom and those same boosters I’m talking about that have been directed at asset values more broadly.

These boosters are twofold.

The first is the massive spending by governments and the accompanying massive budget deficits. In the ‘old days’ those deficits were what was called ‘sterilised’ (an interesting word in the context of the virus) by the government issuing bonds.

In simple terms, the government pumped out the money with its deficit spending; then it sucked it back in with the bond issues.

Well, all that was dumped after the GFC, essentially continued ever since, and got a renewed boost this year after February’s crash.

Yes, when the governments switched to massive budget deficit spending, they still issued bonds to private investors, but then the various central banks set about buying those bonds, pumping the money straight back into the system.

The combination poured first trillions, then combined with fresh investment cash, tens of trillions of dollars into the global money pool.

With central banks all-but in complete global co-ordination, keeping rates at zero, it meant all that money was desperately looking for assets, not cash, that would generate a return or capital growth.

The first time “we” did it, after the GFC, it was supposed to be unwound, to get back to some sort of normality.

The Fed tried to do it — it raised interest rates, it cut back QE (quantitative easing). But then essentially gave up before the virus; before going all in again after it.

The entire world is now hooked on the cheap money and budget deficits.

Look at Australia. The Reserve Bank has promised to keep rates at zero for three years at least. Yes, our deficit might fall, but there’s zero prospect of it getting anywhere near balance this side of the first colony on Mars.

And what happens when, not if, we hit another bump? Both government and central bank will just double down again. There’ll be huge deficit spending; rates will stay at zero — they might even go negative — and the central banks will ‘buy’ the government bonds.

Can this go on — a third time, a fourth time — without it all imploding? The only clear-cut and extremely unpleasant circuit-breaker would be all that loose money sloshing around the world finally triggered a serious surge in conventional — goods and services — inflation.

Indeed, the RBA has that — in its hopes, a mild version of that — as its specific target.

It hasn’t happened so far because of the unique combination of factors which have kept (most) ordinary goods and services from rising in price — China as the world’s low — so far, ever lower — cost manufacturer, tech, the internet, the switch to virtual reality and so on.

There are, to me, two big dangers.

Artificially zero rates and force-fed money printing has completely disrupted the critical signals you need for a healthy, properly functioning economy.

Secondly, the big message is against selling an asset, almost any asset. You’d be deciding to swap an asset that could generate usually tax-advantaged capital value growth and probably earn you an income for zero-interest and zero capital-growth cash.

Indeed, as discussed last week, you are being offered all-but free money — a 2 per cent interest rate — to borrow and buy property.

Not only are you being discouraged from selling an asset, borrow and — try to — buy more. It’s a universal one-way bet and that’s disturbing and very dangerous.

Originally published as The world is now hooked on cheap money and budget deficits