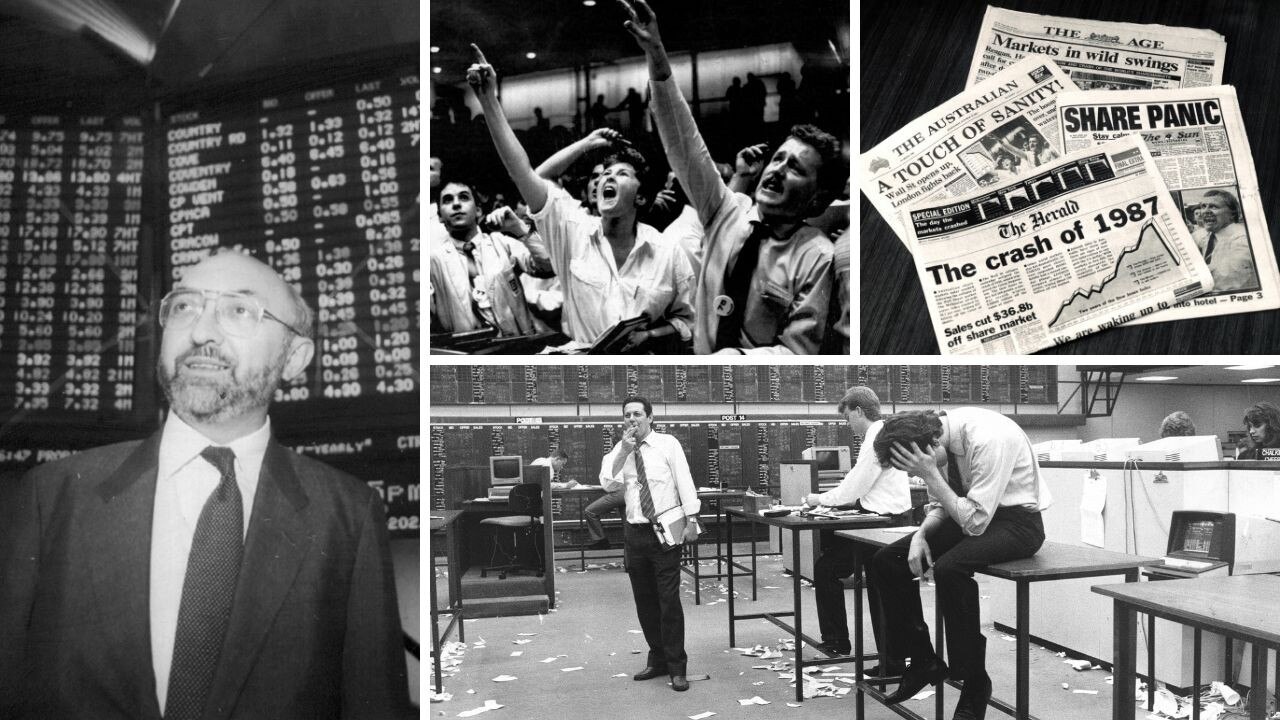

Terry McCrann: A market boom made by central banks

Sure as day follows night, share and property prices keep rising. But are we all being led up the garden path, asks Terry McCrann.

Terry McCrann

Don't miss out on the headlines from Terry McCrann. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Many, many years ago I met an analyst who predicted Wall St’s Dow Jones index would rocket all the way to 3000.

That mightn’t seem all that impressive after the Dow overnight Monday hit a level ten times that, 30,000; but at the time of the prediction — way back in the early 1980s – the Dow was less than 1000. My Wall St visitor was making a convincing case that share prices would more than triple.

Similarly, in the dark days after the Global Financial Crisis in early 2009 when the Dow had been slashed to around 7000, there were analysts – a few, sitting out there fairly lonely in left field – predicting it would go to 30,000.

Well, it now has. If you’d put $100,000 into the Dow stock at the bottom in 2009, you’d now have $428,000 (ignoring currency changes).

But if indeed, you’d put the $100k in at not even just at the exact bottom in March, but broadly around it, you’d have turned it into $150k in less than nine months. The same’s the case with our local ASX this year.

The long and the short of this rise and rise again in the Dow – the broader markets on Wall St, as the Dow only covers 30 stocks, and indeed our downunder ASX, along with just about every share market in the world – is a mix of two titanic dynamics (note the lowercase-t; I’m not drawing ship-and-iceberg analogies).

It is critically important to understand the difference.

In the good old days, there were two linked truths about ‘the market’ – Wall St and all the derivative markets, as they were even then around the world.

The first is that individual share prices were a reflection of, a valuation of, a company’s operating profit and dividend and the prospects for both – related to interest rates. And with both – share prices and rates – in turn related to the state of the economy.

So, broadly and crudely, share prices rose into an economic boom; and then rising interest rates would bring both the boom and the bull market to an end. Until rates then fell and the cycle started again.

The second truth was that after such a fall share prices would always get back to their previous peak and then rise further.

Why? Because share prices in aggregate – ‘the market’ – were the capitalised value of the economy; and in the great rising prosperity after 1945, as economies kept growing so did the market keep rising.

Apart from, but always also through, the ‘interruptions’ along the way to both economy and market.

This is what essentially drove that tripling in the Dow from 1000 to 3000; and then was the major but not the only factor that took it to and above 10,000 leading up the GFC in the ‘Great Prosperity’ of the 1980s, the 1990s and the 2000s.

It also remains as the core bedrock of market valuations, just as property prices are never going to go back to the levels of say 1980, or even indeed 2000: all the valuation relativities have ratcheted permanently higher.

But from around the mid-1990s a new macro factor came into play. It contributed to the rise in the Dow to around 14,000 before the GFC; it has been the primary driver of the subsequent doubling in share markets since.

This is central banks – led off by the US Fed, supported by the European ECB (and the Bank of England, but it’s really too small to matter beyond the shores of Albion) and Japan’s BoJ – and now, belatedly joined by our own Reserve Bank.

A long-forgotten Fed head opined that it was the job of the Fed to snatch away the punchbowl when the party became too rowdy. He was talking about the Fed raising rates into my boom described above.

In the 1990s, legendary Fed head (legendary, especially in his own mind) Alan Greenspan would repeat that aphorism, while actually initiating the practice of doing exactly the opposite: filling the punchbowl with more 150 per cent-proof monetary hooch when and if the party flagged.

And so we got excessively low interest rates – eventually all the way down to zero and in some countries actually negative – and the money printing known as QE (quantitative easing).

It is this which has been the driver of the Dow from the pre-GFC 14,000 to today’s 30,000.

That’s importantly, the overall market, whether considered as the 30-stock Dow or the 500 biggest companies in the S&P 500. And both indirectly – Wall St drags us up – and directly – with our own zero rates and QE – also our market.

I suggest this is fundamentally artificial in boosting both share and property values; and seriously distorting of the signals we need for healthy economic and investment activity.

It is also extremely dangerous and ultimately unsustainable – we are going to need 200 per cent proof hooch at the next ‘hiccup’. But it is also the reality we all have to live with.

Within this broad dynamic has of course been the ‘tech phenomenon’ – Amazon, Apple and Tesla etc there; Afterpay and a few others here – which has seen much, much bigger rises than the overall market.

The NASDAQ is up 74 per cent from its March low. That needs a story all on its own.

But I’ve described the broad journey that took the Dow first from 1000 to 3000, and then to 10,000 and now 30,000.

Originally published as Terry McCrann: A market boom made by central banks