Husband’s death sees Hemstritch donate $8m for cancer research

The harrowing death of her husband is behind Melbourne company director Jane Hemstritch’s donation to set up a new pancreatic cancer research facility.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Melbourne company director, Jane Hemstritch AO, learned about the devastating impact of pancreatic cancer more than a decade ago when her husband, Philip, was diagnosed with the disease.

While he managed to live another two-and-a-half years, thanks to a supportive oncologist, he didn’t achieve his goal of making it to his 60th birthday, dying at the age of 58 on St Patrick’s Day, March 17, 2010.

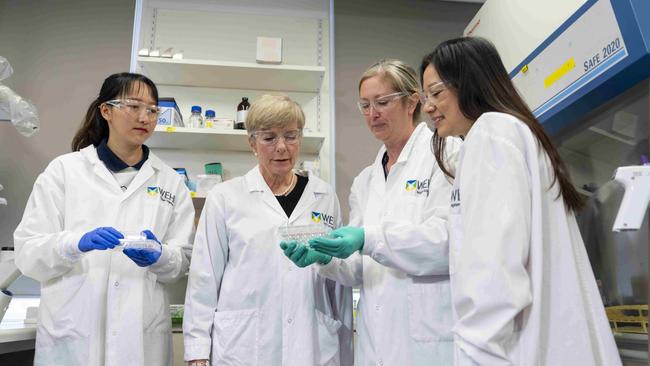

“Philip was very fit and survived for two-and-a-half years from his diagnosis as he had a great oncologist, but for most people it is just brutal,” Hemstritch, the president of WEHI (formerly known as the Walter and Eliza Institute for Medical Research), tells The Australian.

“You only have about six to nine months to live from the diagnosis.”

The harrowing experience of her husband’s life with cancer and his death is behind her determination to do what she can to support research into what is now one of Australia’s deadliest cancers, donating $8m to set up the Hemstritch Centre of Excellence for Pancreatic Cancer Research.

The 10-year investment is aimed at looking for new treatments for pancreatic cancer and creating a new dedicated research centre at WEHI.

The donation includes funding for research collaboration between WEHI and the Garvan Institute of Medical Research in Sydney.

A former director of Lendlease, Telstra, Tabcorp, Santos and the Commonwealth Bank, Ms Hemstritch is a board member of accounting firm KPMG and a director of the Australian Brandenburg Orchestra.

But it is her work with WEHI – which began in 2013 in the years after her husband’s death, and stepped when she became president in 2019 – which has become one of the key focuses of her life.

Her decision to make the donation for a specialist research centre for pancreatic cancer follows years of smaller donations for research into the cancer since her husband died.

Hemstritch studied biochemistry in London but decided laboratory life was not for her.

She moved into accounting and IT, going on to have a 25-year career with consulting firm Accenture, where she rose to the role of managing director of Accenture’s Asia Pacific business.

Her interest in pancreatic cancer has come full circle with a new enthusiasm for what can be achieved through medical research.

She says pancreatic cancer research has not had the support which has been helping to combat other cancers such as breast cancer.

While survivors of breast cancer have gone on to become powerful advocates for more research into that disease, the deadliness of pancreatic cancer means that there are very few survivors who live to argue the case.

“The survival rate with pancreatic cancer is so appalling that I saw that there was nobody advocating much for research funding into it, which is a sad fact of life,” she says.

Some 3,600 people in Australia die from pancreatic cancer each year.

A lack of overt symptoms often means that people do not get diagnosed with the cancer until it is at an advanced stage, with the disease going on to affect nearby organs.

“It’s a quiet killer,” she says.

“You don’t really know you’re ill until it’s far too late.”

More than half of the people diagnosed with the cancer die within the six months of diagnosis, with only 11.5 per cent managing to survive for five years.

While research into breast cancer, skin cancer, prostate cancer and many blood cancers has significantly improved survival rates, progress in research into how to treat pancreatic cancer has been slow.

This could see it become Australia’s second biggest cancer killer by 2030.

Ms Hemstritch is a big supporter of the idea of personalised medicine – the approach used by her husband’s oncologist, where work is done on the specifics of each patient to develop personalised treatment rather than a one-size fits all treatment.

She hopes the Hemstritch Centre of Excellence for Pancreatic Cancer Research will help people rapidly access new, individualised therapies, given pancreatic cancer patients generally have so little time.

“The research team includes clinician-scientists, which will speed up the application of their discoveries to patients,” Hemstritch says.

There are also indications that genetics could play a part in the cancer.

“Around 10 per cent of people who are diagnosed have a genetic predisposition,” she says.

“In my husband’s case this seems to be right as his father also died from the disease.”

She says the goal of the new centre is to improve survival rates for people diagnosed with the disease “so we can lift the current dismal survival rates into something a bit more promising.”

Hemstritch, who received an AO for her services to medical research, the arts and business in the Australia Day honours of January 2023, is a strong supporter of philanthropy for medical research in Australia.

She believes that focusing donations on a specific area- in her case to support research into pancreatic cancer- can be more effective than small donations to many charities.

“If you can focus on a specific issue, it can provide more energy and effort to the people who are on the receiving end of it,.”.

Hemstritch is a big fan of the Snow family in the Canberra area who have established the Snow Medical Research Foundation.

“They have done such a great job with their medical foundation,” she says.

“They donate their money very carefully and they monitor it very closely. It is a textbook example of how people in corporate life can really make a difference. Hats off to them.”

While there is government funding for medical research, private sector philanthropy has the potential to make a big difference.

Hemstritch says medical researchers have a constant “scramble” for funding.

“With some of the National Health and Medical Research Council research grants only about 20 per cent of the applications are successful,” she says.

“That is why private sector philanthropy can be so important as it helps take the pressure off the scientists to have to go after grants and allows them to actually get on and do the research.

“Philanthropy really does help in this field and Australians should be proud of the quality of medical researchers in the country, she says. “Anything we can do to support them is money well spent.”

Originally published as Husband’s death sees Hemstritch donate $8m for cancer research