Global semiconductor chip shortage to drag on until 2025 with a staggered recovery, says Bain & Company

The global semiconductor shortage will continue to cause billions in lost production.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The global semiconductor shortage will continue to cause billions more in lost production of cars, trucks, PCs and consumer electronics and will linger to the mid decade. There seems little respite in the short term with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine impacting the availability of neon, a seminar by Bain & Company has been told.

The global management consulting firm expects some chip shortages to continue until 2025, but there was some short term hope, said Anne Hoecker , Bain & Company Silicon Valley partner. “We think improvements will start to be seen in the second half of this year, but it’s going to be a bumpy road into 2023 and longer,” she said.

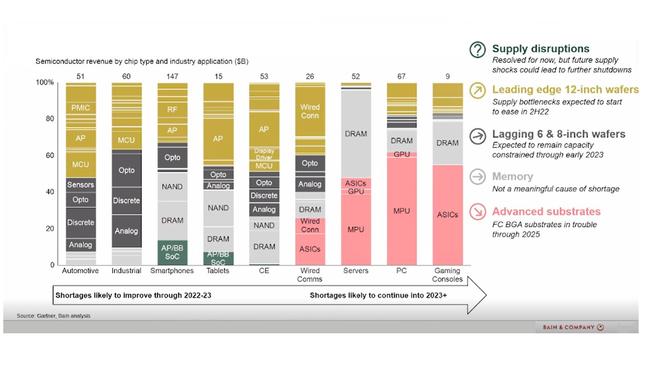

The firm identified four root causes of the shortage, each impacting different types of chips in different ways.

Shortages of computers, gaming consoles, wired communications and servers were likely to persist with the supply of “advanced substrates” remaining in trouble into 2025.

Cars, smartphones, tablets and industrial equipment would be without needed some semiconductor parts until early 2023.

Some relief was expected in the supply of “leading edge” chips in the second half of 2022. These chips were used in most device categories. But many of the same devices also used older chips such as sensors which were expected to remain in short supply until early 2023.

This meant a staggered recovery with different chips becoming more available at different stages.

Covid was to blame for lockdowns in countries such as Malaysia, Vietnam and The Philippines which impacted manufacturing. There was severe weather disruption such as storms in Texas in February 2021 that caused about $US195bn in damage. The storms impacted Samsung, NXP and Infineon.

There were industrial accidents such as a fire in January 2022 in Berlin at ASML Holdings, the world’s biggest supplier of photolithography systems. These systems etched designs onto silicon wafers.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine had imperilled up to 70 per cent of the world’s semiconductor grade neon, which comes from two Ukrainian companies Ingas and Cryoin. Production stopped in March.

Ms Hoecker said manufacturers were looking at recycling neon, using less of it or turning to alternative supplies. While manufacturers had enough neon backup for now “if the conflict continues for quite a long time that of course could change.”

There were serious equipment shortages going forward. Equipment used to produce older chips was booked out with long lead times for buying additional equipment and manufacturing capacity. (Click on the image below to enlarge.)

The underinvestment in newer leading edge chips meant limited manufacturing capability to meet growing global demand, as was the case for cutting edge semiconductors.

There was some optimism with governments investing in the semiconductor industry. The investments included a proposed $US52bn over five years in the US, $US450bn over 10 years by Samsung and SK Hynix in South Korea, and more than $US200bn allocated in China from 2014.

Ms Hoecker said the automotive industry would recover better than some others, due to the increased supply of mobile processing units (MPUs) later in 2022.

She said some manufacturers had enjoyed success redesigning products to get around chip shortages. “A lot of companies are thinking about, as they design their products, how they redesign with resiliency in mind.”

Bain & Company San Francisco partner Peter Hanbury said the primary bottleneck was the ability to build substrate factories that supply materials used in chip manufacture.

National security was also a challenge when it came to funding. “It’s not just a matter of are you spending the right amount, but rather are you spending more than others to attract the capacity that‘s going to be built to your geography,” he said.

Originally published as Global semiconductor chip shortage to drag on until 2025 with a staggered recovery, says Bain & Company