How high will interest rates go?

Struggling Australians will hate it, but the reality is the peak of the cash rate may end up being even higher than the big banks forecast.

Interest Rates

Don't miss out on the headlines from Interest Rates. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Earlier this week the RBA raised interest rates for the 10th consecutive meeting, with rates now sitting 3.5 per cent above where they were when the rate rise cycle began.

With commentary from the RBA continuing to suggest that further rate rises lay ahead, the big question is what will be the peak of the cash rate and when will that occur?

As things currently sit, three of the big four banks, Westpac, ANZ and NAB expect a peak cash rate of 4.10 per cent, with the Commonwealth Bank calling a peak of 3.85 per cent.

Interest rate futures markets have a similar viewpoint, with a peak cash rate of 4.15 per cent currently pencilled in for October.

However, its worth noting that recently financial markets were pricing in a cash rate as high as 4.35 per cent.

To get a handle on where rates could ultimately peak, we’ll be looking at two separate groups of factors, the international and domestic inputs into the RBA’s decision making.

The Domestic

On Wednesday RBA Governor Philip Lowe made headlines after stating: “We are closer to the point where it will be appropriate to pause interest rate increases to allow more time to assess the state of the economy.”

But despite some of the hopeful sound bites this has created, it came with a lot of equivocations from the RBA Governor.

Lowe went on to warn “that further tightening of monetary policy is likely to be required” and that “if we don’t get inflation down fairly soon, the end result will be even higher interest rates and more unemployment”.

Meanwhile, the forward-looking indicators for the labour market continue to remain in positive

territory despite falling from last year’s peaks.

According to the ABS Job Vacancies index job openings remain 91% higher than their pre-Covid peak, which was recorded in February 2018.

At the same time the proportion of businesses reporting a job opening stands at 27.7 per cent,

compared with just 11.0 per cent prior to the pandemic.

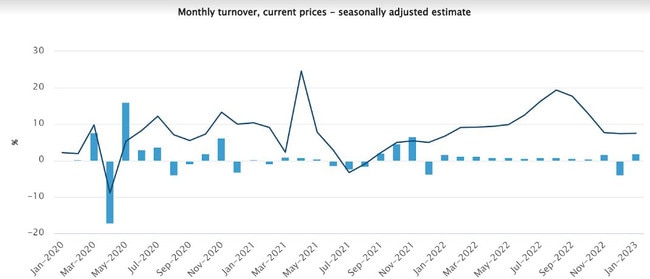

In the world of retail sales, its more of a mixed bag. While January saw retail sales up by 7.5 per cent year on year, this figure is not adjusted for inflation and is actually below the headline rate of CPI inflation.

It is however worth noting that the ABS has had issues with seasonal adjustments related to changed consumer spending patterns since the rise of Black Friday sales.

Falling inflation adjusted retail sales is not necessarily the precursor of rates being paused. In the United States inflation adjusted retail sales peaked in March of 2021, yet inflation has continued to accelerate and the U.S Federal Reserve continues to raise interest rates, with a 0.5 per cent rise later this month firming as a possibility.

The International

Despite Australia’s status as an island nation, when it comes to the flows of capital and the pricing of interest rates, no nation is truly isolated or insulated from the moves of global bond market or those of the U.S Federal Reserve.

Between the late 1980s and late 2017, Australia was afforded a degree of protection from these global forces due to having a higher central bank interest rate than the United States.

At the start of the 1990s, the RBA cash rate was 9.25 percentage points higher than the equivalent American central bank rate, the Federal Funds Rate.

Since 2018, that has all changed. The relative spread between the RBA cash rate and the U.S Federal Funds Rate has blown out to as much as 1.65 percentage points in favour of the U.S, which has been a headwind for the strength of the Australian dollar.

With the U.S Federal Reserve continuing to raise interest rates, central banks around the world have responded in kind to address their own domestic inflationary pressures and to prevent the potential devaluation of their currency’s if the U.S rate rises too far above their own.

This set of circumstances is putting the RBA in a challenging position. They could begin to temper their rate hikes earlier than expected, but that could put downward pressure on the Australian dollar, potentially leading Australia to import inflation from overseas due to the weakness of our currency.

At the same time, if we see a rerun of the rise in government bond yields which occurred between August and October last year, this could create a further headwind for the strength of the nation’s currency.

The Outlook

To say that economists and commentators were divided on the future course of Aussie interest rates would be an understatement. On one hand there is three of the big four banks pencilling in a 4.1 per cent cash rate for later in the year, while there are others such as Commonwealth Bank which are talking up the possibility of a pause from the RBA as early as the next meeting.

With the world’s largest household debt load by some metrics, the stakes certainly are high. Even with today’s 3.6 per cent cash rate, the RBA estimates that 14.6 per cent of mortgage holders would have negative levels of spare cash after paying their loans.

Ultimately, the peak level of the cash rate is a key piece of the puzzle that will decide the trajectory of everything from home prices to the broader economy. Another is how long rates end up staying at these relatively high levels.

A 4.1 per cent cash rate may be entirely tolerable for most mortgage holders if its only for a short time, but today’s 3.6 per cent cash rate may be too much for the economy to handle if it remains in place over a long time period.

Originally published as How high will interest rates go?