Behind Victoria’s plan to stop Tasmania’s green power going national

The days could be numbered for the little-known regulatory quirk that has given a boost to Victorian power customers at Tasmania’s expense.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There’s an almighty battle brewing in the cold deep waters of Bass Strait, pitting the Victorian government squarely against Tasmania. The fight is over electricity and who should foot the bill for transmission over the 370km high-voltage extension cord that sits below the sea floor. Basslink connects the two states and offers a 500 megawatt backdoor plug from the island into the national electricity market.

At one end of the cord is the green hydropower generated by Tasmania. At the other is Victoria’s massive but creaky power grid dominated by the brown coal generators of the La Trobe Valley.

Under the Basslink’s contract, which expires mid-next year, the Tasmanians pay for the cost of the transmission through invoicing that goes to the state-owned generator Hydro Tasmania.

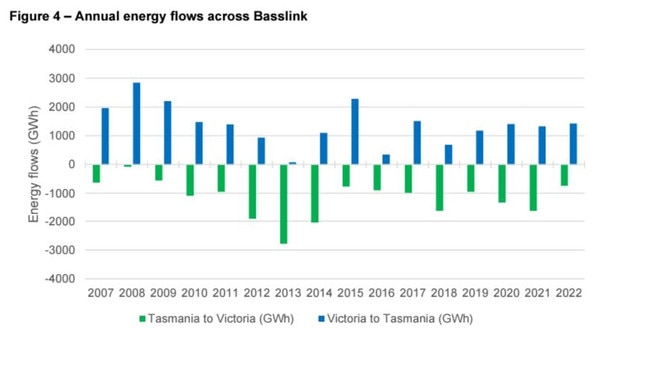

And while power travels two ways, the arrangement means Tasmanians don’t get the full benefits of trading directly into the national electricity market that takes in the east coast and South Australia. The trading is done by Basslink, rather than Hydro Tasmania. As a general rule, Tasmania has enough generation capacity to meet all its needs, but variation in rain, the occasional drought, or maintenance meeting with spikes in demand can leave it short.

In the winter months, Tasmania also has a surplus of cheap green hydro power. And this is often the time when the eastern states need extra supplies to crank up their heating.

But the current contract where it’s classed as a network service provider means there’s little incentive or ability to export the island state’s power, particularly when it’s the Tasmanians paying for the delivery or wearing the risk of futures pricing between the Victorian market and Tasmania.

The owner of the 20-year-old Basslink is gas pipeline player APA, which bought the transmission line out of administration in 2022, and that’s when the new stopgap deal was put in place.

Nearly 18 months ago APA applied to the national energy regulator for the Basslink cable to be a regulated transmission network provider, a move that plugs it directly into the national electricity grid and gives the regulator more control and visibility over the flow of power in and out of Tasmania. The move would deliver better use of existing infrastructure and help smooth some of the wild swings in the nation’s power market.

But this also means the cost of the transmission network is born by the biggest users. Victorians will have to start paying up. And while Tasmanians will still have to pay for the use of Basslink, APA calculates the average cost per Victorian household for the cord to become a fully regulated transmission will be $1 per household per year. That’s one dollar. Victorian businesses that use more power will pay $20 more a year.

Under the proposal, Tasmanian households will see their cost of using Basslink fall to $6 annually, from around $8 currently.

The Victorian government says no. The Victorians argue electricity consumers across the state currently pay nothing in terms of prescribed service costs for Basslink. Conversion will result in Basslink’s costs being shifted to residents and businesses.

The government also fears Victorians would lose out, given the current agreement only exposes any power exports to the Victorian regional reference price. Being part of the national network could see Tasmanian power sold anywhere in the Australian grid where the price is highest.

“This would not provide Hydro Tasmania with an incentive to maximise exports when the Victorian RRP peaks. This will, in turn, drive up wholesale prices in Victoria,” the Victorian government said. In short, the Vics want to keep all that cheap Tassie power to themselves.

APA argues Basslink has the potential to deliver a boost to the national electricity market and help with its goals to go green. With more co-ordination, Tasmania’s hydro dams can act as long-term energy storage that can “firm up” intermittent renewable generators such as wind and solar.

There’s also the issue of much of Tasmania’s energy generation capacity being wasted.

The state regularly receives more rain than its dams can hold, which needs to be spilt from the dam. Instead, this capacity can be sold cheaply into the national grid at peak evening times, helping to lower prices across the country.

APA says under the current model for Basslink revenues are unregulated. “If Basslink is converted … any incentive for the interconnector to be constrained will be removed, ensuring that Basslink is available to transport as much renewable energy between Tasmania and Victoria as possible”. The proposal comes as a second high-capacity line connecting Tasmania and Victoria – backed by both state governments – is being planned. The link was aimed at tapping the massive new wind projects being planned by Hydro Tasmania.

The 750MW Marinus link remains in pre-feasibility stage and while the operation is scheduled for 2029, this timetable already looks like it is slipping.

This has the potential to impact the valuation of Basslink, including putting an even higher valuation on the asset under the AER’s regulated model. A higher valuation could further lift the potential revenue take for Basslink.

Modelling by consultants ACIL Allen estimates the total costs of conversion of Basslink to a regulated entity to be $1.4bn, although that’s over the more than two decades remaining operational life of the asset. The funds will be used to pay for ongoing operating and capital costs.

EY, another consultant, modelled Basslink would deliver up to $4.2bn benefits to the electricity market over the next two decades. This clearly outweighs the costs.

The EY figure takes in a range of changes to the national electricity market and assumes at least a single link of the Marinus cable is built. (There are two 750MW cables planned over time).

The benefits are in the form of lower capex and fuel savings through better access to existing and low-cost Tasmanian generation. It also says there would be less pressure to build new gas peaker plants on the mainland, further lowering costs.

APA initially proposed that the revenue-sharing costs be split 9 per cent to Victoria and 10 per cent Tasmania. This is given the size of the relative markets of where the biggest end users of the electricity are based. Following the strong pushback from Victoria, it later revised down this split down to 75 per cent, with Tasmanians carrying 25 per cent.

Both Hydro Tasmania and the state government are strong supporters of Basslink becoming a regulated transmission line.

“Basslink’s regulation is in the best interest of Tasmania, and the NEM more widely. Conversion would bring surety to the sustainable and open flow of electricity between Tasmania and Victoria, which is an essential element of the national energy transition, and particularly important for energy security in Tasmania …” the Tasmanian government says in submission to AER.

It warned if the current temporary contract remains in place, flows of electricity between the two states would be at the control of Basslink, and would be driven by profit maximisation incentives. Rather than a regulated market.

“As Australia moves through the energy transition … our existing reliable deep storage and world-class untapped renewable reserves (energy and capacity) becomes increasingly important,” the Tasmanian government says.

The AER is expected to make its final decision on Basslink by February.

Until then, Tasmanians will keep footing the bill for Victorians.

eric.johnston@news.com.au

Originally published as Behind Victoria’s plan to stop Tasmania’s green power going national