ANZ-Suncorp deal: High-stakes ACCC ruling needs to be tested

The competition regulator faces its own credibility test after rushing to embrace an unseen force to block ANZ’s $4.9bn Suncorp deal.

Business

Don't miss out on the headlines from Business. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The competition regulator faces its own credibility test after rushing to embrace the invisible force of “co-ordination” as the key reason to block ANZ’s $4.9bn move on Suncorp Bank.

The decision handed down by the Australian Competition & Consumer Commission is built around wild competition theory; ignores its own evidence; and takes a worryingly unsophisticated view of the market it is regulating.

By heading down this path a lot is at stake. The ruling substantially increases the hurdle for future mergers – even beyond banking.

Both ANZ and Suncorp have signalled an appeal to the ACCC’s rejection of their planned banking deal. This should be welcomed. Such a significant decision deserves scrutiny if it is to be taken seriously.

Much of the ACCC’s finding hinges on the idea that the removal of Suncorp from the banking market – that is folded into ANZ – would bring a return to the “co-ordinated behaviour” of the big four banks.

It draws heavily on the evidence of Mary Starks, an economist and former top UK competition regulator in a report prepared for the ACCC, who argues there is significant co-ordination between the major banks. She points to the big four lenders passing on Reserve Bank interest rate hikes in full on mortgages as evidence of a market vulnerable to co-ordination. She ignores every bank including the smallest credit unions are also passing on rate hikes as a way to recoup higher funding costs.

Starks dismisses the rise of lender Macquarie, which has snapped up market share from the major lenders, as simply having a “tight strategic focus”. Investments in technology and digital innovations by the big banks such as ultra-fast loan approvals, is labelled by Starks as “largely reactive” rather than serious efforts to boost market share. No acknowledgment is given to the rapid collapse in bank profit margins since the exit of more significant regional competitors St George Bank (to Westpac) and BankWest (to CBA).

Still, Starks’ findings cascade through the ACCC’s ruling, which advances the theory that in a market with competitors of equal size there is little need to compete for customers or innovate.

In other words it is a world of “live and let live” and the exit of Suncorp, a relative minnow, would create a greater risk of co-ordinated conduct. Here it assumes each bank and their investors will be forever happy with their corner of the world and won’t do anything to rock the boat.

Until now Australia has tread carefully around co-ordinated conduct and regulators around the world also acknowledge it is a blunt tool to block mergers mostly because it alleges a pattern of behaviour in the future that is hard to prove today.

The US Federal Trade Commission prefers to see evidence of previous collusion or even failed efforts of collusion as something that gives weight to co-ordinated conduct in its merger rulings.

In her submission, Starks pushes back over this notion, saying no evidence of past co-ordination is needed for the behaviour to occur in the future.

Co-ordinated behaviour is for the most part something we all want to believe – that the big four banks are intuitively working in lock-step to carve up the nation’s mortgage market. It’s simplistic and ignores that both the ACCC and Productivity Commission have previously said evidence has fallen short of co-ordinated behaviour between the banks. The ACCC’s case on blocking the Suncorp deal should be built around facts over an adventure.

Office recession

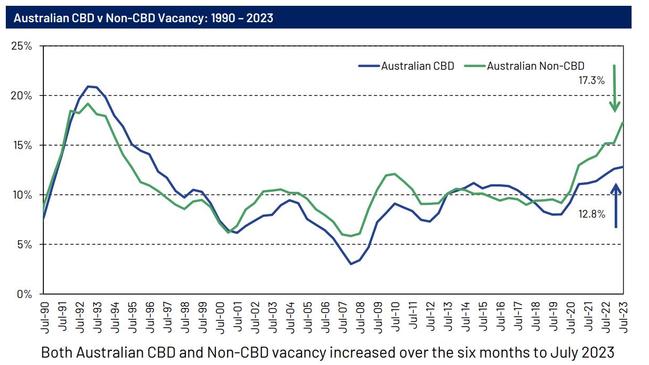

The rate of empty offices across Australia’s CBDs and beyond are now pushing levels last seen in the 1990s recession.

And with an investment strike in new towers almost certain to follow, city and suburban developments could be put on ice for the coming decade as owners struggle to find funds to replace older buildings to keep tenants coming back.

Figures from the Property Council of Australia show there still needs to be a further shake-out in office values before the market can find its base with national vacancies running at 14.1 per cent in the June half. This is up from 13.4 per cent in the December half.

A move in vacancies to 15 per cent will set alarm bells ringing with more financial pain to come.

The level of office buildings standing idle follows a backdrop of a desperately tight property market and surging residential rents. But office buildings aren’t easily retrofitted or are costly to convert to residential. At the same time, owners of towers are holding out hope that a better leasing payday will arrive again.

The vacancy numbers represent levels last seen coming out of the 1990s recession and even then with a slowdown in pace of development, it took more than a decade for vacancies to fall below double-digit levels. A slowing economy and the prospect of higher interest rates for longer means the market will stay under pressure.

But the office market and the relationship between businesses and their workers has fundamentally changed. This is yet to fully dawn on commercial property investors, meaning it could be decades before the market finds its balance again.

Every capital city with the exception of Canberra is facing double-digit vacancy rates. Sydney and Brisbane are just under 12 per cent while Melbourne, once the power of the nation’s CBD market is at 15 per cent. Even boom time Perth has hit 16 per cent vacancy while Adelaide is closer to 17 per cent.

However, it is across the Melbourne and Sydney fringe CBD and their suburban locations where the serious longer-term problems are setting in.

On Melbourne’s ageing St Kilda Road, which is competing against the flashier Docklands, one in four offices are sitting vacant. So too in North Sydney up to nearby St Leonards.

Parramatta in Sydney’s west, which has seen a wave of development, has struggled to lure more corporate clients to set up their back offices outside the CBD.

In total the average non-CBD vacancy rates are running at recession levels, some 17.3 per cent are empty which is the 1990s peak. With the CBDs likely to fill out first as landlords lure tenants with gyms, modern fit-outs and green building standards, some older suburban offices will unlikely be let out again.

The changing work habits of workers are well known through the Covid-19 pandemic, with many office staff having flexibility to work from home. Companies too are being more discerning on the way they use office space and are leasing out smaller floor plates.

Even buildings with big tenants in place are being used less frequently. Efforts from the likes of Commonwealth Bank and others to have staff in the office at least half the time are so far having mixed results. This will all factor into calculations for their long-term office needs.

The one silver lining is the stressed properties are no longer held on bank balance sheets like in the 1990s, which at the time represented an almost fatal blow for Westpac and severely damaged ANZ for almost a decade. Today property is held largely by super funds and other big pension investors.

And while that sounds just as worrying, they have a longer-term time frame and buildings have much lower debt which means they can better ride the cycles. It also means longer-term investors are prepared to hold out, potentially for years, hoping for a leasing payday.

Super funds from AusSuper, Cbus and Hostplus have suffered valuation hits. Listed investor Dexus has taken more than $1bn in writedowns across its portfolio.

There’s still a pipeline of developments committed with more than 1 million square metres of net office stock set to enter Australia’s CBD over the next three years and most of this will be into oversupplied Melbourne and Sydney. Newer buildings and environmentally friendly offices have little trouble finding tenants but these are adding to pressure on the long tail of old stock. Figures from global leasing agent CBRE show Sydney has some of the oldest office stock going – although behind Manhattan and San Francisco – with more than 70 per cent of Sydney’s office towers built before 1994. It just happened to coincide with the last recession.

johnstone@theaustralian.com.au

More Coverage

Originally published as ANZ-Suncorp deal: High-stakes ACCC ruling needs to be tested