Condobolin mums fear health system has abandoned them

A town in NSW’s central west is experiencing a baby boom, but the local mothers say they have been abandoned by the healthcare system.

Bush Summit

Don't miss out on the headlines from Bush Summit. Followed categories will be added to My News.

If a baby cries in the middle of the bush, and there are no midwives to hear it, does it really make a noise?

These are the thoughts that haunt regional mums, who say the health system has abandoned them.

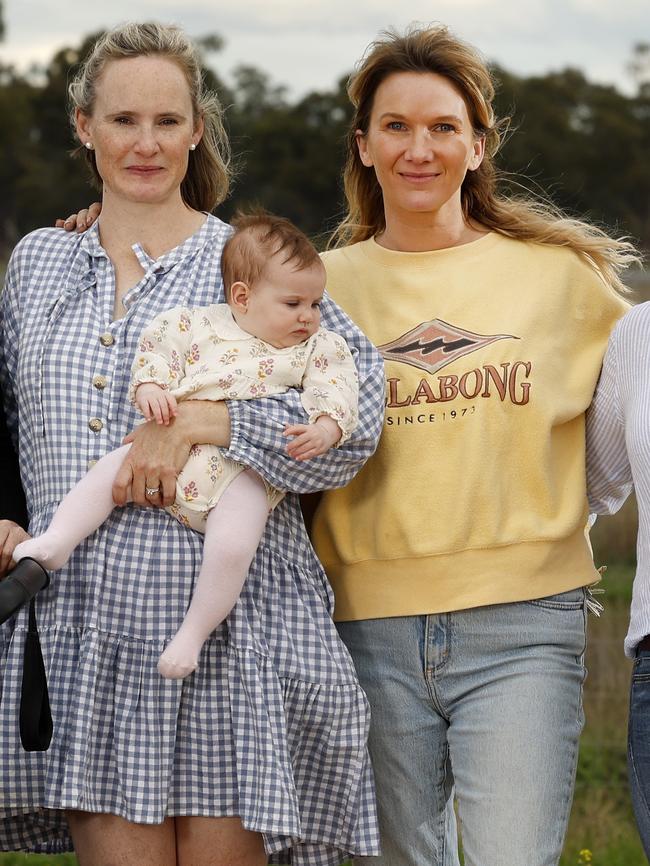

In Condobolin in NSW’s central west, the local region is experiencing a baby boom. Yet, local mums say there are minimal prenatal or post-natal care options in the area.

For first-time mum Becc Kontrec, who gave birth in Forbes last year, the lead-up to her birth was traumatising.

“You hope for the best but need to plan for the worst,” Ms Kontrec said.

“There’s so much that isn’t offered in our area.”

While her birth went smoothly, she was paralysed by thoughts of what could go wrong.

“I know Forbes wouldn’t have had the services to help me if things went wrong, I would have had to have been transported to Sydney,” she said.

“I thank my lucky stars that it all went fine.”

While Condobolin does have a hospital, it no longer has the capacity to deliver babies.

It means that pregnant women must travel over an hour to Forbes or Parkes or, in serious cases, be transported to Orange or Sydney.

It also means that when a baby comes unexpectedly, there are few local medical professionals who can help.

While the mothers commended the extensive and incredible work of the midwives and community nurses in the area – including individual stories of midwives’ around-the-clock commitment to conduct home visits, travelling large distances to manage vaccinations for children and going above and beyond in their roles on a daily basis with limited resources – they said it was no longer sustainable, particularly as the population grew.

When mother Casey Pawsey’s waters broke early for her third child, there was no time for elation. All she could think was, “How do I get to a hospital? We don’t have time.”

She was rushed to Condobolin Hospital, where the only doctor available was on a TV screen.

“He was telling them [the nurses and ambulance paramedics] what to do, but they were obviously too scared to do what he said.

“It was scary, all I could do what hope everything would be okay.

“You could just see it in their face. You could tell they were freaked out.

“There needs to be more education and training around birth and labour,” she said.

Other mothers say they have had to fight for medication and support that would be solved instantly in the city.

Mother Gini Hall was diagnosed with gestational diabetes during her first birth in Sydney. Recognising the symptoms in her second birth, she alerted her regional midwife. However, she said nobody had followed up.

“I had to call my midwife, I had to call Parkes, I had to call Orange, and Forbes. Everybody kept telling me to call someone else,” she said.

She says she had to fight to receive insulin. When her son was born, his blood sugar levels were so low he “nearly died” and had to be placed in special care for three days.

Long wait times and limited support have become the norm. When a regional ultrasound picked up a hole in Ms Hall’s baby’s heart, she had to wait five weeks for a cardiologist to see her son.

“I chased a cardiologist for five weeks. I spent five weeks not knowing the size, or how detrimental it was. I was calling every couple of days for five weeks. They drop these things so easily on you, but there’s no one there to follow it up.

“Your baby has a hole in it’s heart, no one is chasing it up. You’ve got gestational diabetes, no one is following it up. You have got to chase your own issue,”.

When one baby begins crying, a mum picks him up and quietens him with a smile. “Shhh shhh – you get what you get, and you don’t get upset.”

The other mums laugh. It’s a saying they teach their toddlers and bubs in preschool. But in many ways, it’s what the health system has taught them, too.

They speak about their tales lightheartedly, but there’s a darkness in their eyes. They know that the stories they are telling us will never be tolerated in the city.

Other mothers spoke of being pushed out of the hospital shortly after giving birth. One mother, Georgie Browning, had her babies in Sydney. She said her Sydney experience could not be more different from that of her country friends.

“In the city, if you have a caesarean, you are in hospital for three days at a minimum. You come out here, and girls are clapped out of the hallway because they are brave because they are being discharged four hours after giving birth,” said Ms Browning.

She’s one of the many mums who have lost faith in the regional health system, instead opting to use the private system.

Those who do, pay for it. After experiencing complications in previous pregnancies Ms Browning made the decision to give birth in Sydney.

“You can only get the high level of care and treatment in Sydney. After having complications, Sydney was the only place I felt safe,” she said.

However in order to access this care, like many mums, it meant spending thousands in travel and accommodation fees to be near a hospital ahead of her birth.

The mothers said local nurses need to be educated in midwifery and taught about common birth conditions to look out for.

“If you can’t provide services to our area, then educate people you do have already. Educate more nurses in our hospitals. Don’t give them a full midwife certificate but just educate them and upskill them so they know what to do in an emergency,” she said.

GP SHORTAGE, HOSPITALS WITHOUT STAFF OR BEDS CREATES BUSH ‘BREAKING POINT’

Regional NSW is facing a health crisis, with patients left lying on emergency room floors and entire towns without maternity services or doctors.

An investigation by The Daily Telegraph has found NSW’s health system is at “breaking point”, with a new report from the Select Committee on Remote, Rural and Regional Health revealing the state government is failing to adequately improve rural staff retention and recruitment.

NSW Health Minister Ryan Park labelled the revelations “concerning” and has vowed to launch an investigation.

The crisis has sparked some nurses and doctors to blow the whistle on severe failures within the system, with one nurse from Coffs Harbour Base Hospital warning it was only a matter of time until a patient died due to a shortage of beds.

“Our department is becoming more unsafe as we are forced to place patients who are critically unwell in the waiting room for up to six hours while they await an appropriate bed,” they said.

The nurse, who wished to remain anonymous, said they had been forced to treat patients on blankets on the waiting room floor because there were no available beds or chairs. “I have had no one die on my watch yet, but it feels like a game of Russian roulette,” they said.

Wagga Wagga state independent MP Joe McGirr, a former emergency physician, said “regional healthcare in NSW is the worst it’s been for many years”. “Health staff are being pushed to breaking point,” said Dr McGirr, who chaired the NSW Legislative Assembly Select Committee which released its damning report.

Difficulty accessing healthcare has become the norm in regional Australia. A 2023 Bureau of Health Information Survey of patients who attended rural EDs found that of the 1,992 patients who said that at the time of their ED visit, they thought their condition could have been treated by a GP, 42 per cent said the reason they didn’t see a GP was because that service was closed. Another 7 per cent said it was because there was no GP close to where they live.

It's a problem the Murray River town of Balranald knows first-hand after the town’s only GP left this year. A doctor now visits the town once a week but locals said that was unsustainable. “Our next closest GP is more than 100km away and it is not uncommon to wait six weeks and sometimes … more to see a doctor there,” community leader Rachel Williams said.

NSW Opposition regional health spokesman Gurmesh Singh said stories from people on the ground showed how dire the situation was.

“We need to see these services bolstered, not continually stripped back,” he said.

Mr Park said improving access to healthcare in the bush was a core priority for the government, “with a focus on addressing worker shortages … as well as $1bn in regional and rural health infrastructure in the state budget”.