Vale Ted Matthews: A sombre salute to the first and the last

IF it’s possible to describe as lucky a young bloke thrown into the horrors of Gallipoli, then Ted Matthews was very fortunate indeed.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

IF it’s possible to describe as lucky a young bloke thrown into the horrors of Gallipoli, the Western Front and the Great Depression, then Ted Matthews was fortunate indeed.

He had two great strokes of luck he believed saved him in the life-and-death lottery of Australia’s bloodiest war, which left 60,000 Aussies dead.

But he rode that luck to live happily — if modestly — to the grand age of 101, claiming a place in history as the last of the original Anzacs. Of the 16,000 Australian and New Zealand troops who splashed on to the fatal shore at Gallipoli on April 25, 1915, Mr Matthews ended up in the 1990s as the lone survivor.

ANZAC LIVE: REAL STORIES, REAL TIME

WAR WIDOWS’ SPECIAL FLIGHT TO TURKEY

HARBOUR BRIDGE A CANVAS OF COURAGE

Ten WWI Diggers outlived him and as a result he became something of a forgotten Anzac.

But none fought alongside him on that single day a century ago now commemorated like no other.

Ted Matthews was the very last of the very first, so if this month’s 100th Anzac Day is all about remembrance, then the knockabout Sydney carpenter deserves a special place in the national consciousness.

His first piece of good fortune came when he enlisted early as a 17-year-old. It so happened the recruiters that day were signallers. Ted knew Morse code so they gladly accepted him after a

brief test.

“They took me in, otherwise I would have been in the infantry. And if I was in the infantry I don’t think I would be here now,” he recalled in later life. His biggest stroke of luck bordered on the miraculous. During the Gallipoli landings he was hit in the chest by shrapnel but the blow was cushioned by a thick pocketbook his mother had given him.

“I had a bruise but that shrapnel could have hit me in the face, anywhere,” he said.

“It’s all a matter of luck. As we used to say, if your name was on it, you’d get it.”

He was heartily sick of war by the end of the aborted Gallipoli campaign, which cost 11,400 Anzac lives. But much worse was to come on the Western Front, where the carnage was four times greater.

WARREN BROWN’S GALLIPOLI DIARY DAY 2

IN THE FOOTSTEPS OF MY HERO, MY DAD

Mr Matthews was part of the smashing victory at Villers-Bretonneux, France, on April 25, 1918 — three years to the day after the Gallipoli landings — that paved the way for the Allied victory.

When the guns of war fell silent on November 11 — his 22nd birthday — Mr Matthews returned to his trade as a carpenter, married and raised two daughters during the Depression.

“I went away a boy and came back a man,” he said.

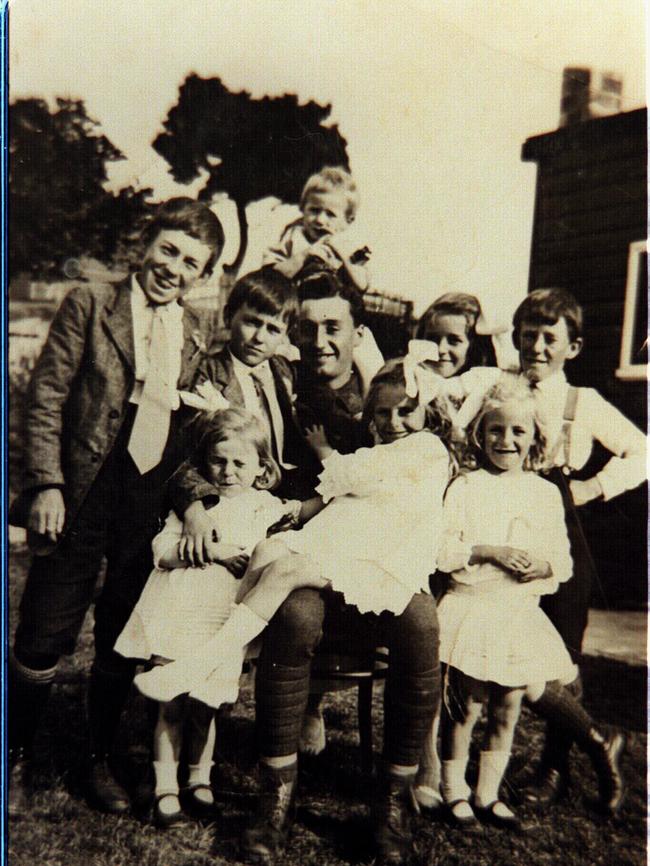

He already knew all about tough times, being one of six children of a paper bag merchant born at Leichhardt in inner Sydney. But times were about to get a lot tougher.

He used to walk 20km twice a week from his home at Campsie to Circular Quay to register for work, then to Railway Square to pick up rations, then back home.

Ted Matthews never regarded himself as a hero. And he knew his place in history was a mere matter of chance: “Somebody had to be the last one, and it just happened to be me.’’

But he did typify his generation. He was an ordinary man pitched into extraordinary times, combining a larrikin’s sense of adventure with a decent bloke’s sense of duty.

He bore no animosity to the Turks, appearing in photos with his old foes on an official pilgrimage to Gallipoli in 1990.

When prime minister John Howard visited him on his 100th birthday at the RSL veterans’ nursing home at Collaroy, a sister suggested he offer his VIP visitor one of the Anzac biscuits my wife had baked for him.

“He can get his own,” Mr Matthews laughed.

“These are all I’ve got.”

He detested war but was a staunch supporter of Anzac Day, arguing: “The younger generations don’t know the horrors of war.

“They need to be reminded. That’s what their forefathers died for — to preserve their freedom and way of life.”

He fired just one shot at a Turk, saying: “I hope I missed the poor bugger.”

Mr Matthews eventually outlived both of his wives and one of his two daughters before his death in 1997.

His definition of an Australian could be just the tonic the nation needs after the sombre reflections of the 100th Anzac Day.

“Even in the worst situation, the Aussies would see the humour, if there was any humour to be seen at all,” he said.

“An Aussie is someone who can see the humour in anything.”

Originally published as Vale Ted Matthews: A sombre salute to the first and the last