The promising VFL footballers who became Anzacs and fell at Gallipoli

AMID gripping Anzac Day matches, spare a thought for the VFL players at Gallipoli. Collingwood’s Alan Cordner was among them. | Anzac Day games in Superfooty

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

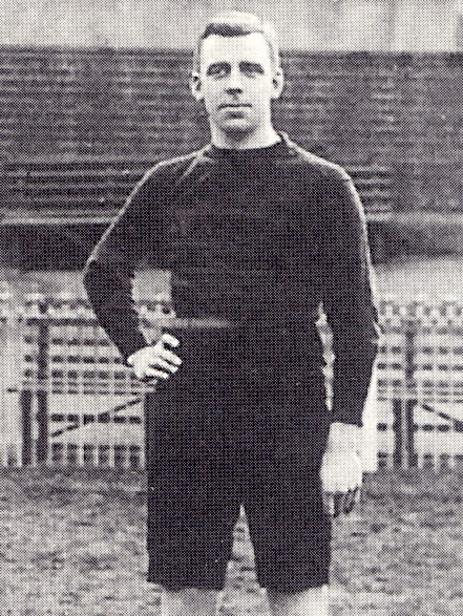

JOE Pearce never stood a chance.

In the early light of morning, and against the crack and echo of machine gun and rifle fire hitting water and things far more vulnerable, the Melbourne footballer turned Corporal from the 7th Battalion sat helplessly alongside his mates from ‘D’ Company.

Their boat was heading towards shore. It was April 25, 1915.

Only a few hours earlier Pearce had been tucking into a hot meal aboard the transport Galeka and peering out against what author Les Carlyon described as “the black mass of the (Gallipoli) peninsula beneath the stars”.

Now he and his mates were caught under heavy fire. Four boatloads of the 7th Battalion had been told to head north towards Fisherman’s Hut, but in doing so, had been subjected to a barrage of bullets that would leave many of them dead or wounded.

Pearce, a football amateur who refused even to play for expenses, would be killed before his boat slid into the sand and shells on the shoreline. He was 30.

Eight months earlier, in a toast given to him by the football club he had represented in 152 games, the champion defender explained why he had chosen to defend his country’s freedom and way of life.

Pearce explained at the time: “I have thought this thing over, and have considered it every way. I am young, strong, healthy, athletic, and I think I ought to go, and if I don’t come back, well, it won’t matter too much.”

Arthur Mueller ‘Joe’ Pearce was the oldest and most accomplished of the six VFL players known to have died on the day of the Gallipoli landings.

He hadn’t even had the chance to fire a shot before his war was over, with one report detailing his death: “While making for Fisherman’s Hut in a boat ... Pearce was killed by machine gun or rifle fire.” It was said that he was “buried with 30 or 40 others on the beach” at No. 2 Outpost Cemetery, just a hundred in from where those boats would land.

At least he had a grave, and his heartbroken relatives, including a sister who filed In Memoriam notices in the newspaper for half a century afterwards, had the peace of mind of knowing what had happened to him.

Relatives of the other five league footballers to die on that mad and chaotic day were not afforded the same certainty.

All of them — Collingwood and ex-Geelong defender Alan Cordner, former University player and medical student Rupert Balfe, one-time South Melbourne player Charles Fincher, ex-St Kilda footballer Claude Crowl and former Carlton and Melbourne player Fen McDonald — were killed without known graves.

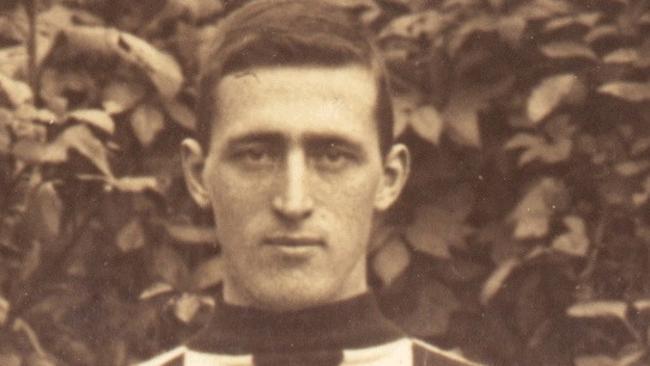

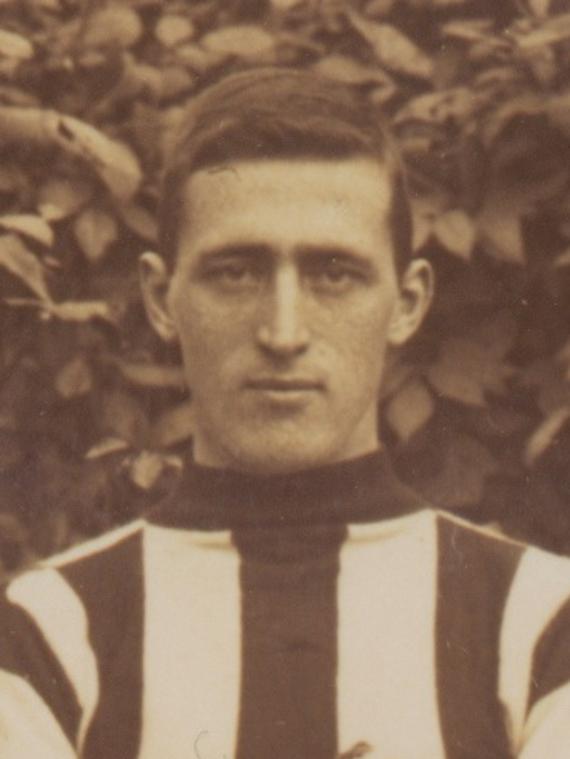

CORDNER had been one of the first footballers to enlist. A clerk from the Metropolitan Gas Works, he was described by his former school as “a rough-hewn stone”.

On a day that dawned with hope, but soon turned to hopelessness, the 24-year-old from the 6th Battalion would need every ounce of that toughness and strength of purpose in the few remaining hours of his life.

After the landings, Private Cordner made his way up the slopes that stood before him, rushing inland with those with him against the constant drill of gun and shell fire.

Confusion reigned. At first he would be listed as missing and later presumed dead when it became apparent he had not been among the confused and the wounded.

One of Cordner’s superiors wrote: “The casualty (Cordner), the informant, and two or three others got separated from their own men ... they were in the firing line about two miles from the beach. The informant was next to the casualty when he was shot. He tried to make the casualty speak and shook him, but could not move him from where he was.

“(The) informant really thought the casualty was dead and admits he may have been mistaken.”

He wasn’t, but others were. And the pain that this misunderstanding and misinformation would do to Cordner’s family back home would be immeasurable.

One nurse told of how a man, possibly Cordner, had been repatriated off the Gallipoli peninsula, and there was even a report he had been sent to England for treatment of his wounds. Another suggested he may have been “adopted” by another Battalion, with the most fanciful being that he had emerged from his disappearance to take part in the August Offensive.

His father pleaded in July 1915 — three months after the landings — “I have not heard from my son ... since his arrival at the Dardanelles.” Still, later, he wrote desperately: “Could you please let me know of his present whereabouts as no word has been received from him since 20th April last, and if he was in hospital, he surely would have sent word.”

Any remaining strands of hope were extinguished on April 24, 1916 — a day less than 12 months from the landings — when Cordner was officially listed as dead. One soldier wrote: “I don’t think there is any reason to doubt that Cordner was lost on the first day at Anzac ... It is with the greatest regret that I can say that one must ... console oneself with thoughts of the gallant way in which he sacrificed his life.”

His old school, Hamilton College, would honour his “isolated heroics” in a moving tribute, saying Cordner was “one of a small party who, penetrating ... inland, found themselves cut off by the Turks. Where better to leave him than on the hillsides of Gallipoli doing his duty.”

Cordner’s body was never found, and neither was the gold watch that Collingwood had presented him on his departure.

BALFE was from the same Battalion, and his debut game for University in 1909 had come in the same team as Cordner’s cousins, Harry and Ted Cordner. Like Cordner, too, he was outflanked and isolated and he would be classified as missing.

One soldier who knew him later remarked: “He (Balfe) was leading ... and very keen, (he) got further on than I did. (But) two of his party came back and said he was killed.”

Another said: “I hear he was seen with a handful of men surrounded by a large of body of Turks, and fighting desperately with bayonets until they were all killed.”

Lieutenant Balfe, the highest ranked of the six League players to die that day, was said to have been in a party near Pine Ridge when they were ambushed. Four years later, after the end of the war, a graves restoration unit found the remains of some of those 6th Battalion men. Balfe is believed to have been one of them.

One of his University friends, Robert Gordon Menzies, penned a poem in his honour, part of which read: “The storms of the battle round him rave/And screaming fury o’er him chants its song,/Sleep, gallant soul! Though gone thy living breath,/Thou liv’st for aye, for thou has conquered death!”

Menzies would be the nation’s prime minister by the start of the next world war.

THE exact detail of Fincher’s death remains unknown, though it is believed this former footballer with South Melbourne and Essendon’s VFA team had been struck by a bullet while making his way across Anzac Cove with the 5th Battalion.

Essendon’s VFA side had presented him with a wallet, cigarette case and match box in club colours before he left Australia. Long after his death, a parcel arrived for his shattered parents containing the damaged wristwatch and wallet.

There were some eerie links between Crowl and McDonald. Both were country lads, born a year and a bit apart. Not only would they make their VFL debuts on exactly the same day — on opposite sides — in 1911; less than four years later they would die on the same day.

Crowl was a farmer from Poowong, having made his debut on a day when the majority of the Saints’ playing list had been on strike due to team selection and squabbling. A private in the 8th Battalion, it is not known how he died. With no known grave, his name is commemorated on the Lone Pine Memorial.

McDonald, who hailed from Nagambie, has his name there too. A century on, their names remain forever linked in death, as they had been in life.

Originally published as The promising VFL footballers who became Anzacs and fell at Gallipoli