Risk-taking pilot Ross Smith a Great War hero

HE WAS a pilot. A risk-taker. And he’d head up, destroy the enemy and be back on the ground before his breakfast went cold. Meet Ross Smith — one of the most celebrated aviators of all time.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

ROSS Macpherson Smith began his military career crawling on his belly up the tawny ridges of Gallipoli, trying not to get his head blown off in that mad, wild country of treacherous ravines and snipers’ dens.

He ended his service to Australia flying high above the earth as one of the most celebrated aviators of all time, having spent part of the Great War as the pilot for the fabled T.E Lawrence of Arabia, who described him as “an Australian, of a race delighting in additional risks’’.

In his book the Seven Pillars of Wisdom, Lawrence recounted some of Smith’s wartime exploits at a desert airfield at Azrak, in what is now Jordan.

On one morning Smith had just sat down to eat his breakfast sausages when the cry went up that four enemy planes were nearby. Smith raced to his Bristol Fighter and climbed into the air “like a cat” Lawrence wrote. He targeted the biggest plane, a German DFW, and quickly reduced it to a cloud of black smoke as it hit the ground.

“Five minutes later Ross Smith was back and jumped gaily out of his machine, swearing that the Arab front was the place [to be].”

His sausages were still hot.

Smith had just started on the toast and marmalade when he was taking off again in pursuit of more enemy machines.

Like fellow aviation pioneers Charles Kingsford Smith and Charles Ulm, Smith began his war service as a foot soldier on Gallipoli watching in amazement as Wing Commander Charles Samson and others of Britain’s Royal Naval Air Service photographed and bombed the southern half of the Turkish peninsula and provided some cover for the invading troops.

Smith was awestruck by the majesty of the flimsy machines.

He was the son of a Scottish outback station manager and was working as a warehouseman for the Adelaide merchants Harris Scarfe when he enlisted, aged 21, just two weeks after war was declared in August 1914.

Within six weeks he had been promoted from private to sergeant.

He landed at Gallipoli on May 13, 1915 with B Squadron of the 3rd Light Horse.

By September, the solidly built youngster with green eyes, thinning fair hair and a butterfly tattoo on his left arm was a second lieutenant with higher aspirations. Much higher.

Gallipoli was a disaster. Smith was invalided out with a stomach infection two months before the Australians were evacuated in December 1915, but he took part in the Allies’ first victory against the Turks at the Battle of the Romani on August 4, 1916, when the enemy was driven into the deep sand east of the Suez Canal.

He became an observer on reconnaissance aircraft and then in July 1917 began training as a pilot with the Australian Flying Corps.

He was credited with shooting down 11 planes and was awarded the Military Cross twice and the Distinguished Flying Cross three times.

At the end of August 1918, Smith took charge of a giant Handley Page 0/400 bomber, complete with its 30m wingspan and two massive Rolls-Royce Eagle engines, and flew it from Cairo to Azrak with his mechanic Sergeant Jim Bennett.

On board were supplies of fuel, oil, bombs and ammunition as well as tea for T.S Lawrence, whose Arab soldiers, on seeing the plane approaching, went wild, firing their guns into the air in celebration, much to Smith’s chagrin given his volatile cargo.

Two weeks after the Armistice, with the world now opening up more than ever to the idea of fast international travel, Smith was chosen to fly the Handley Page on the first aerial expedition between Cairo and Calcutta, a journey that took 11 days.

The following year, Australia’s Prime Minister Billy Hughes offered a prize of £10,000 to the first Australians who could fly from England to Darwin. With just two years’ experience as a pilot, Smith was chosen to captain a Vickers Vimy four-engine bomber on the greatest flight ever attempted.

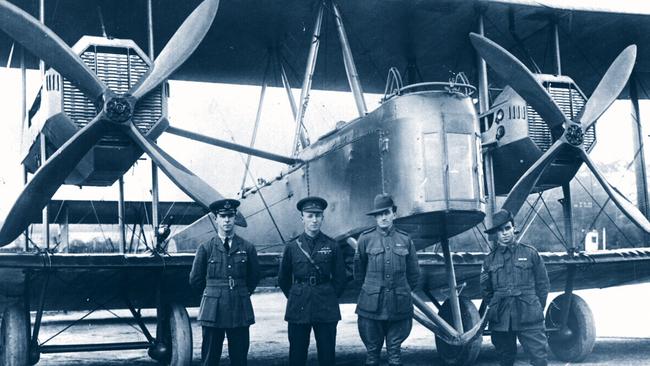

The machine was registered as G-EAOU, which the crew said stood for “God ‘Elp All Of Us”. Smith chose his brother, Lieutenant Keith Smith, as his navigator and co-pilot. Jim Bennett and Sergeant Wally Shiers were the mechanics.

The four men took off from Hounslow in London on November 12 and flew straight into a snowstorm that blasted them in their open cockpits. Ice covered their goggles so the aviators sat frozen in agony with their bare eyes smashed by winds of 140kmh.

For the next 27 days and 20 hours they endured perils and privations, through blizzards, rainstorms, tropical heatwaves and muddy landing strips before arriving in Darwin.

The brothers were knighted and the four split the £10,000.

Among the first to congratulate them were two other Australian wartime pilots Hudson Fysh and Paul McGinness, who a year later with Fergus McMaster, a World War I gunner and dispatch rider, registered a company called Queensland and Northern Territory Aerial Services Limited — now known as Qantas.

The Smith brothers then planned a round-the-world flight in a single-engine Vickers Viking, starting on Anzac Day 1922.

Nine days earlier, Ross Smith and Jim Bennett decided to give their new aircraft a thorough examination at Brooklands airfield, south of London. They were waiting for Keith to join them, but his train was running late so they took off without him.

The Viking performed splendidly for the first 15 minutes. Keith arrived at the airport, breathless after rushing from the station, just in time to see the Viking’s 15m wingspan begin to shake and the machine nosedive towards the earth. It broke apart as it flattened an iron fence.

Amid the wreckage Jim Bennett was moaning, but by the time the ambulance men extracted him from the twisted metal his moaning, and his breathing, had ceased forever. Ross was trapped in his seat, a long gash all the way down his face. Keith, whose life had been spared by a late train, fell to his knees and wept beside his brother, who was dead at 29.

Originally published as Risk-taking pilot Ross Smith a Great War hero