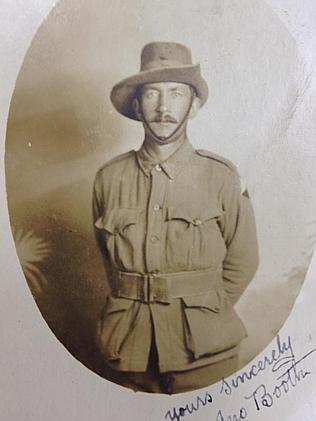

Private Jack Booth: a soldier’s legacy lives on through his diaries

PRIVATE Jack Booth chronicled his time at Gallipoli, through battlefields and hospital beds until his luck ran out.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

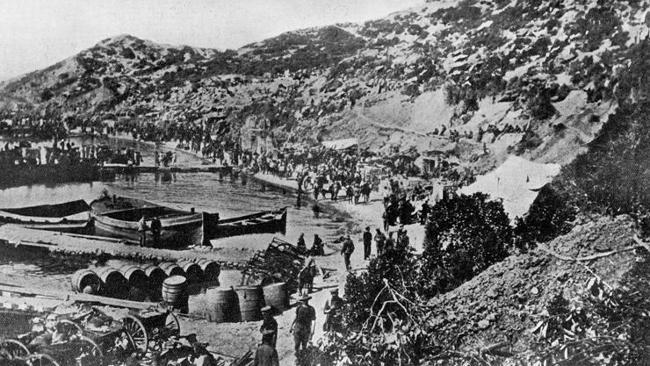

PRIVATE Jack Booth stared at the “huge dark mass” ahead.

He saw dotted lights and jets of flame. He heard machine guns and the boom of shells.

Alongside him, on board, everyone whispered. Gallipoli beckoned, and Booth felt “mingled awe and trepidation”.

It was August, 1915. Booth, a shipwright from Sydney, had wanted to be here sooner.

His first attempt at enlisting had failed, presumably for medical reasons.

He had thought of home often in his training in Egypt, sending handkerchiefs and brooches home to a favoured aunt, Portia.

His family had thought of him, too. That’s obvious in the masses of correspondence from Glassop St, Balmain, a few years later, when Booth’s mother Ada received news that her boy would not be coming home from war.

Almost a century on, it’s easy enough to plot Booth’s path to October, 1917, through battlefields and hospital beds, to a shell crater in Passchendaele, Belgium.

What’s harder to grasp is the confusion that bled through the Booth family’s grief: the fretting after Jack was first reported missing; the hope he may have been taken as prisoner; the bureaucratic back and forth of repeated confirmations of his death; finally, the realisation that their beloved would have no known grave.

The Booths would have to be content with planting trees in nearby Elkington Park. For the rest of us, Booth’s legacy still sparkles, in a neat hand on pages corrugated with age.

In his diary, at Sydney’s Mitchell Library, his family has added an opening inscription: “He saw the Light and followed it to the End.”

Booth’s Gallipoli writings were collated while he was laid up in an English hospital in early 1917.

His account offers the wide-eyed wonderment of an observer dropped in a foreign world. He sounds more like a whimsical observer than a machine gunner in the 20th battalion.

Like other Australians, he did not recount triumphal battles. Instead, he spoke of many close calls at Gallipoli.

Given our knowledge of his impending death, his account seems to imply that he used up his luck there.

It also points to an unbendable truth — over almost nine months, nowhere was safe on the Turkish peninsula.

Booth could have died from the time he was towed ashore in that pre-dawn. He saw men hit by stray bullets before his boots hit the pebbled shore.

North of Anzac Cove, a day after landing, Booth took his post and saw men shot by snipers.

This was an “anxious time” - “I shall never forget the feeling that came over me, when I was faced with the grim reality,” he wrote.

“When daylight appeared, sniping by the Turks was prevalent and it was difficult to locate where it came from; in fact, it came from all points of the compass.”

He was astonished when a shell took a leg off a sergeant and wounded others — astonished, that is, that the shell did no more damage.

Another shell flattened and buried Booth in dirt but otherwise left him unharmed.

Booth also saw moments of kindness shared between combatants.

One took place on October 12, after the Australians tossed bully beef tins into the nearby Turkish trenches.

Men from both sides peeped across no man’s land. An ad hoc armistice was called.

The Turks threw over cigarettes and tobacco.

“Then a Turkish machine gun played slowly along the bottom of our parapet, so as to give us warning, then bombs were thrown as usual,” Booth wrote.

He chronicled the privations of everyday life: the lack of sleep, for example, and an absence of fresh vegetables.

He wanted his “readers”, as he headed his diary, to know what life was like.

Booth spoke of the stench of burning and decayed bodies.

Of dysentery and infections from the slightest wound — Booth himself had a septic hand for a month.

He froze at night, when he scratched at lice, and burned during the day, when he swatted at flies.

He skirted over the perils — so many Diggers did in their recordings of their war experiences.

Leaving Gallipoli itself was chief among these. By then, Booth wore a long beard.

Booth was in the second last grouping to leave, after dark on December 19. It was a clear and moonlit night, Booth wrote. He left with “mingled feelings of regret”.

“The campaign had been a failure,” he wrote, “yet a splendid one, but it was not the fault of the troops: it was the fault of those who planned it.”

Stupid luck had spared Jack Booth the shells at Gallipoli. Stupid luck condemned him to a shell in Belgium two years later, when it seems a German shell exploded overhead and Jack Booth had no time to shelter.