Our Anzac heroes will never die while their families live to tell their tales

FOR the proud who march, medals not of their own gain pinned to their chest, war is a great paradox.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

FOR the proud who march, medals not of their own gain pinned to their chest, war is a great paradox.

Its brutality is foreign, far beyond the realm of their experience, yet deeply personal.

Its sacrifice and demand for bravery is bewildering, at stark odds with their relative comfort and fear-free existence. But yet understood.

Their heroes are no more, yet they remain — their gripping stories etched on to the hearts of those who sat at their feet and imbibed the terrors and triumphs and then passed them on through the generations.

OUR SPECIAL SECTION — ANZAC CENTENARY

SIX BROTHERS IN ARMS WERE LOST TO WAR

A SOLDER’S LEGACY LIVES THROUGH DIARIES

SCROLL DOWN FOR FAMILIES’ DIGGER STORIES

SCROLL DOWN PAST THE PHOTO MONTAGE BELOW TO READ PHOTOGRAPHER CHRIS MCKEEN’S STORY OF HOW THE PROJECT CAME ABOUT

They never met but Walter Wakeling has been the unseen guide of his great-granddaughter Olivia.

His story of astonishing courage on the blood-soaked soil of northern France is worthy of having been repeated, on loop, in the teen’s ear.

Walter was just 19 when he joined the New Zealand No. 1 Field Ambulance Medical Corps. He survived Gallipoli before serving in Egypt and France, finally discharged on May 23, 1919, having been decorated with the Military Medal.

The citation demands utmost respect: “For conspicuous gallantry and devotion to duty while supervising the evacuation of wounded under shellfire … He continually exposed himself in supervising the evacuation of wounded and he also personally led the stretcher bearers through a heavy barrage.’’

A life worthy to remember and draw inspiration from, Olivia said.

“While we all have different reasons Anzac Day is special to us, for me it keeps the memory of my great-grandfather in my heart,’’ the Hills teenager said.

Hayley Stephenson has gone from hearing to telling. Every Anzac Day she sat with her late father and read from a book — her grandfather’s WWI diary, a chronicle of bleakness and camaraderie amid the 1st Battalion of the Australian Imperial Force in France.

CLICK HERE TO READ THE WONDERFUL STORIES IN FULL

While the diary of Vivian Thomas Stephenson has been archived at the Australian War Memorial, the cursive text still dances through Hayley’s mind, enough to be able to recount the stories to her own children Lilly, 12, Brinlee-Rose, 6, and Emma, 1.

“I don’t think they have a lot of understanding of what it’s about,” the Berowra Heights mum said.

“Being a kid, you just think, ‘Oh yeah, they were in the war’ but they don’t understand what he went through.”

They will. The storytelling will go on until it’s unforgettable.

These truths are beginning to hit home for Annandale sisters Madeleine and Trinity de Lance, aged 10 and 6. Through their mother’s retelling, they are grasping the tales of their great-grandfather Cecil Duke, one of 13 siblings whose male brood all served in wartime. Or their great uncle Jack Tucker who left as a 19-year-old, rose through the ranks to become a flight sergeant before being killed in action.

“The older you get, you appreciate how people suffered for the good of others,’’ mum Stieve De Lance said. “It was incredible bravery from people so young.’’ Thomas Shanahan loved each time his grandfather received a new knee. It was time to take his place again.

“We would all love sitting on one of his five new knees,’’ the Crows Nest grandson said.

But he grew to comprehend what the knees of Sergeant Reginald Clement Shanahan represented.

The one-time accountant spent three and a half years in the notorious Changi prison in Singapore. His knee was shot out by his captors to prevent his escape and to strip away his stoicism. It didn’t work. “The point of the POW camp was to break them down emotionally and there was no way that grandad was about to let that happen, that wasn’t in his nature and it earned him respect among his captors,’’ Mr Shanahan said.

Not all stories have to be told as a memorial. Greg Van Esveld, a RAAF flight sergeant, gets to walk today with his family who have borne the burden of him being away from home, in the firing line, on repeat. “I’m proud of him,” his 11-year-old daughter Madison said. “We watch Dad when he’s marching and you feel proud that they’re there and that they went, and they’re helping our country.’’

That is the key. It doesn’t matter whether they were brave, victorious or earned medals.

They went. The story could stop there — respect gained. Pass it on. With N

SCROLL DOWN PAST THE PHOTO MONTAGE BELOW TO READ PHOTOGRAPHER CHRIS MCKEEN’S STORY OF HOW THE PROJECT CAME ABOUT

CLICK HERE TO READ THE WONDERFUL STORIES BELOW IN FULL

CHRIS MCKEEN’S PLEASURE AT TAKING THE PHOTOS

“NEVER — ever — volunteer for anything.”

Having left school and voluntarily enlisting in the New Zealand Army, this advice had landed several months too late.

Now several years later, it rang in my head when my boss called me over and asked if I was interested in taking on a project.

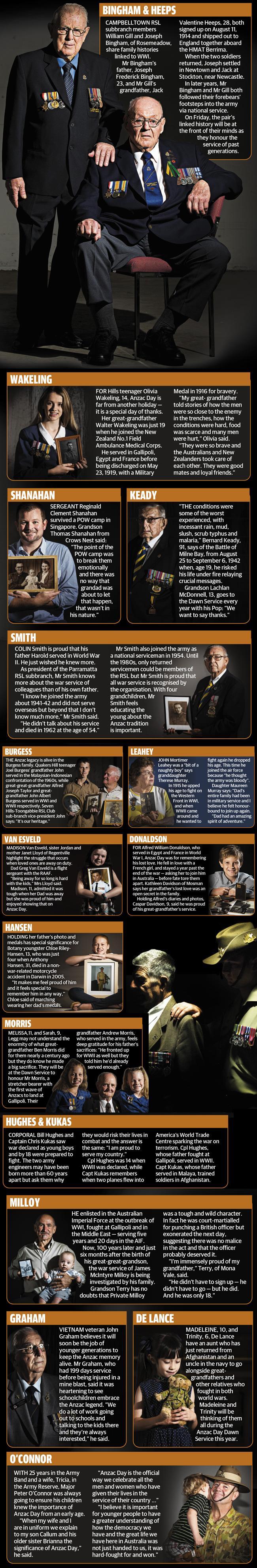

The project, it would turn out, was to travel the length and breadth of Sydney, taking photos of family members paying tribute to military relatives.

As a photojournalist, we get the chance to participate in a huge variety of photographic assignments and Anzac Day is an annual event that always provides opportunities for colourful, emotive images.

This opportunity didn’t disappoint.

Our network of Sydney journalists put out the word, and with the assistance of the Legacy Foundation and local Returned Services Leagues, we came up with a list of subjects to photograph.

Our creative team had supplied me with a brief, so it was up to me to sort the lighting and composition issues.

Over the next fortnight I photographed people from Erina to Campbelltown, from Surry Hills to Penrith.

It was rare that I had access to a photographic studio. As necessity is the mother of invention, I ended up photographing in some rather unusual locations.

In Penrith I used a boardroom. In Castle Hill it was a basement car park and in Parramatta and Five Dock a wall in the RSL. The Mitchell Wing of the State Library provided inside and outside backdrops, while in Berowra Heights I was able to shift a couch and shoot inside a lounge, and Erina’s location was a busy shopping centre.

Photographically, simplicity and ease of transport played a large part on how I approached this task.

A single speed light was positioned high and right of the camera, nearing a classic ‘Rembrandt’ lighting style. The flash was directed so the feathered edge of light fell across the subject, but also fell on a silver reflector that was positioned just out of shot beside the subject, providing a cool fill light.

But the locations came a very distant second to the people I met, and the stories they brought with them.

There were photographs and gallantry medals from World War One and soldiers that had followed their father’s footsteps and themselves enlisted to fight in World War Two.

I met soldiers who had stepped up, volunteering in case the conflict escalated in Malaya and soldiers injured in Vietnam.

Three year old Connor has a father who is still in the Army after 26 years, and after tours in East Timor, Afghanistan and Iraq, Madison is proud her father is still in the air force.

Many ex-servicemen know the importance of support and camaraderie and are engaged in organisations like Legacy and RSLs across the country.

After serving almost ten years with an elite British unit and deploying to Afghanistan, Adrian Talbot is now the Wounded Liaison officer for the Soldier On charity, an organisation that makes a difference by making a developing connections between the wounded soldier and their communities.

Today the Australian and New Zealand militaries are comprised of volunteers who, for many reasons, choose a life filled with sacrifice.

For this project, over twenty families volunteered their precious time to publicly pay tribute to family members who have made this challenging decision.

I’d like to thank the families that took the time to accommodate me for this assignment, and hope that you make it to a parade or service to honour servicemen and women from both countries, past and present.