New and older generations remember Anzac and the diggers

IGNORING the famous phrase “lest we forget”, for decades Aussies did their best to push Gallipoli into the back of our minds. Patrick Carlyon examines what’s changed.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

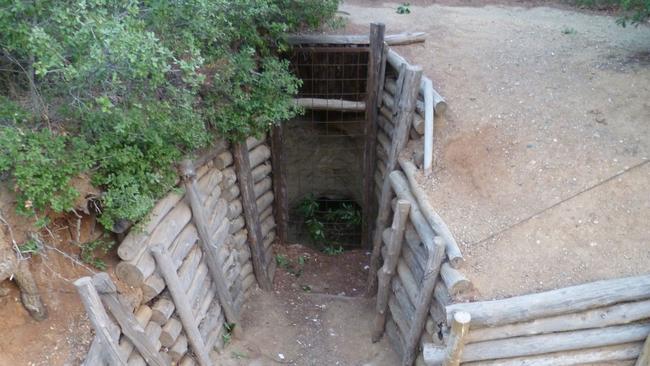

JOHNSTON’S Jolly is not at all like its name suggests. The Anzacs held the Gallipoli ridge only briefly in 1915: after being overrun, they machine gunned charging Turks here a few days later. All bar one of the Anzacs soldiers buried in the cemetery are unknown. The lonely lawn shares the haunted quality of the nearby Baby 700 Cemetery, where at least the winds blow the ghosts away.

It seems right that Johnston’s Jolly is now shrouded in pine trees. The site is a starting point for souvenir hunters, who scrape and rustle for ball bearings and shrapnel like hidden animals in the scrub: it’s said the more intrepid of them risk more macabre finds.

Such explorations lead a solemn pursuit straight back to 1915. The Gallipoli battlefield that this week prepared for a 100th anniversary commemoration bears only rough comparison, if invasion is a loose term, and if chaos can be applied to a mood of disorganisation that falls short of panic.

Johnston’s Jolly doesn’t feel like a sorrowful place at all. A Turkish boy and girl giggle as they fence with play swords in trenches once considered among the most exposed at Gallipoli. Their mothers stand nearby, their faces hidden by traditional Muslim dress.

Alongside, an Australian coachload of tourists huddles around a Turkish guide. A pair in the group whispers about the stubby holders for sale, perhaps at the Turkish stalls just up from Quinn’s Post, where Australians and Turks once lobbed food at one another when they tired of throwing bombs. The Turks are still “giving away” food — based on the exchange rate, anyway — along with fridge magnets and dolls and easy smiles.

Gallipoli was never just a history lesson, even for those gawk at the heights above Anzac Cove, and search for explanations. Anzac, never more than now, is a state of mind. Those who try to frame guidelines for Anzac Day’s rightful place stand accused of many things. The crowds at Gallipoli expose their greatest failing as naïveté. Anzac has no set of rules. It demands little except a willingness to bow to the imagination.

Perry Richardson came here this week to accompany his father. The Newcastle man’s great uncle fought in the Battle of Bersheeba in 1917. At the Nek, where wave after wave of Australians were dispatched to certain doom, Richardson was overcome by sentiments that flood most visitors. What was it like? How would I have fared? “It’s very hard not to be enthralled by it all — and annoyed by what happened,” he says.

Nearby, at the Baby 700 Cemetery, Joe Drobinski is laying a wreath for a forgotten ancestor, a 21-year-old who never came home to marry and have kids. “It’s not only for him but everyone else who has fallen ...” he says. His voice catches. “It’s such a waste.”

For Hobart’s Arthur Orchard, whose father Bert fought here, it means visiting the grave of his father’s friend, Dick Parry. For Allan Kemp, of Brisbane, it means laying out the medals of three generations of family at Anzac Cove, asking for a moment to gather his thoughts, then explaining that his gesture represents the futility of war.

For Australian clients of Kenan Celik, probably the most thorough guide on the peninsula, it means an enduring grasp of the campaign’s failings, and a desire to find out more about the Turkish commander (and later Turkey’s president) Mustafa Kemal.

For Caitlyn Dickason, five, from Whittlesea in Victoria, it means being gently introduced to the gravity of loss and her Anzac pedigree at Beach Cemetery. It also means being photographed, like so many others, old and young, at Simpson’s grave.

Sudden wells of emotion have been common here in recent days. Contagions take off in cemetery visits so that entire groups appear to have been delivered the worst of news. The rosemary sprigs, the lingering hugs — these are not new either. Yet it wasn’t always the case.

Teenagers here this week are far more likely to bow to Anzac sentiment than their parents or grandparents once did. It’s a distinction that different generations within the same families of Gallipoli Victoria Cross recipients openly acknowledge.

The roads at Gallipoli have not always been clogged with buses, tourists, and various officials who, at times this week, seem to outnumber the civilians. The poppies, like clots of blood on the foreshore at Fisherman’s Hut, sprouted unnoticed for more than half a century. The Anzac dead have long laid in cemeteries as neat as golf greens. For most of that time, they have been honoured by almost no visitors at all.

Writer Alan Moorehead lamented the emptiness in the 1950s. For a decade or more after World War II, Turkey closed the land from the public. Moorehead’s castings take you to the creaking gates of the British cemeteries at Cape Helles to the south of Anzac.

Here lie 16-year-old boys, once the shiny-faced promise of little towns in nowhere parts of England. Sometimes, if you dig deeper, you find that the hopes of entire streets were dashed in a Gallipoli afternoon.

First the boys were lost, then they were forgotten. There were few picked flowers in these cemeteries, much less the knitted wool poppies that have sprung wild across the Anzac cemeteries these past days. The only visitors, until recent days, anyway, were goats and their shepherds.

Anzac was once consigned to a few faded images and the ramblings of veterans who confided only in others who shared their troubles. Of course mothers wanted to know where their sons lay. They sought photos and identity discs and knowledge, of which there was never enough. But they did not seek to visit.

The first visiting party, after the boneyards were properly reburied in 1919, arrived in 1929. Turkey was a foreign place and a fraught journey. It was not a destination.

An Australian academic used to tell the story of how she was on a cruise through the Greek Islands when she was invited the Gallipoli Dawn service. She duly arrived and was invited to speak. She wasn’t special: so few Australians were there, everyone was asked to speak.

The crowds through long decades would number a few hundred each year. There was plenty to cherish about Gallipoli, but there was a lot to forget as well. The visitors slept among the graves at Ari Burnu and took swigs to keep warm.

That veterans did not speak much to loved ones about their wars seems an almost universal truth, at least according to their descendants at Gallipoli this week. Arthur Orchard’s father Bert scribbled diary entries for four years. Plainly, Bert Orchard was a kindly and thoughtful soul. Yet he didn’t open up to his son. Nor did some Victoria Cross winners, despite the lifelong invitations to do so.

For many diggers, internal conflicts opened domestic battlegrounds that were not spoken of at all. If they talked about Gallipoli, it was usually later in life, to grandkids, say, to set it down before they were gone.

In 1984, about 300 attended the dawn service, many of them veterans returning for the first time. In 1990, Prime Minister Bob Hawke wept at the Lone Pine service. The notion of “Anzac tourism” had arisen. Peter Weir’s Gallipoli enjoyed nightly screenings.

Hawke told about 5000 “pilgrims’, as they would be called, that “ … because these hills rang with their voices and ran with their blood, this place Gallipoli is, in one sense, a part of Australia”.

The crowd at the 85th anniversary in 2000 topped 14,000. Some sported slabs of beer and Collingwood jumpers. It wasn’t all backpackers, as the uninitiated might imagine, but there were Mexican Waves.

Much has changed. The tractors still rumble and the fields are newly tilled, probably for the tomatoes that taste so much sweeter than those back home. Yet the dusty trucks, instead of produce, have been weighed down with portable toilets this week. They hold up the Jandarma (police) with their flashing lights. Turkish flags flutter on every vista.

For the rising number of Turkish visitors, Anzac broadly means one of two things. Gallipoli is a growing place of commemoration, in large part because Australia treats this wild country with such resurgent reverence. It is also a state-sponsored excursion about the virtues of the Islamic faith. Both reasons help explain the 2000 coach loads of Turkish visitors on the Anzac battlefields two weeks ago.

The dawn service itself will be a production unlike any other. At least one veteran attendee grumbles about the loss of its easy camaraderie for the stiffness of protocol.

Saturday’s service will be heavy on ceremony and light on spontaneity. Narrow roads and a new age of terror help explain why the 8120 or more (dead sober) Australian dawn service attendees will have passed through six security checks compared with an airport screening.

They will have waited 12 hours or more, sans sleeping bags — Townsville father-and-son Jason and Joshua Smart, 12, were preparing this week to set out almost 21 hours before the service begins to walk 20km to be there.

The service will feature an audience of Anzac pedigree unrivalled since Gallipoli diggers were invited back for the 1990 ceremony. “Every single piece of the site will have a body on it,” a Department of Veterans’ Affairs spokesman says.

The crescent moon will slide behind the cliffs. An inky light will reveal a white wash on the shoreline, and perhaps the silhouettes of one or two members of the 3800-strong security contingent.

Some here will imagine rifle pops and grunts and splashing and a collective fear of what lay ahead. In the hills above North Beach, men like Fred Tubb and Kingsley Batty and Bert Orchard and Frederick Dyer once clambered into the madness.

Tubb was awarded a VC. Batty added little to the historical record except as a gravesite at Quinn’s Post. Yet these Anzacs all count equally a century later. They all boast descendants who will shiver in the Gallipoli dawn. As one, the descendants may ponder how a nation once tried to forget.

Originally published as New and older generations remember Anzac and the diggers