From Keith Murdoch and Neil Davis to Marie Colvin, war correspondents can change the course of history

THEY are the game-changing moments of history — but for the men and women on the spot, they are laced with danger and moral dilemmas.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

For more than a century reporters, photographers and camera operators have played a crucial role in shaping conflict and public opinion.

From A.B. “Banjo” Paterson’s dispatches in South Africa during the second Boer War in 1899, Keith Murdoch’s famous World War One Gallipoli Letter and Damien Parer’s powerful images from the Kokoda Track, to the modern coverage of conflicts in places such as East Timor, Iraq and Afghanistan news from the front has influenced politicians and generals and altered the course of history.

Bearing witness can be dangerous and it can throw up some disturbing moral dilemmas, but most men and women who compile the first draft of history do so for the love of the story and a quest for the truth.

As the Kiwi WW2 photographer George Silk, who was captured by the Germans in North Africa and escaped, said: “I reasoned that I might do some good for humanity; that, perhaps, if people got a good, rough look at how wars are fought, they might stop future wars.”

Legendary American Vietnam War photographer Larry Burrows also worried a great deal about the impact of his work on those he portrayed.

“It’s not easy to photograph a man dying in the arms of a fellow countryman and later to record the breakdown of his friend. Was I simply capitalising on other men’s grief?

“But I concluded that what I was doing would penetrate the hearts of those at home who are simply too indifferent.”

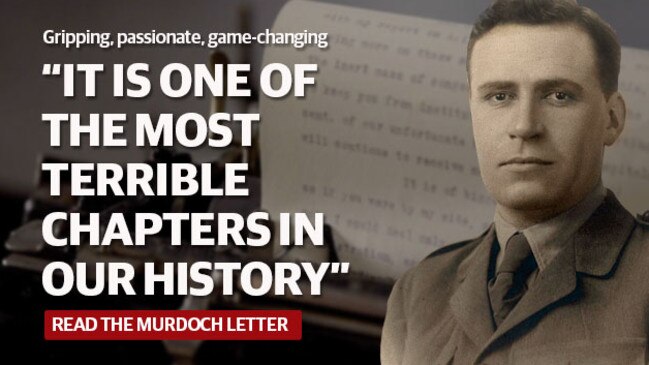

THE MURDOCH LETTER

It is widely acknowledged that Keith Murdoch’s scathing letter highlighting the incompetence of the British Generals running the disastrous Dardanelles campaign brought the tragedy of Gallipoli to an early end.

After visiting the front for four days during August 1915 and after extensive consultations with other writers including British war correspondent Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, Murdoch agreed to dodge censorship rules and pass on a letter penned largely by Ashmead-Bartlett to his friend the Australian Prime Minister Andrew Fisher.

But Murdoch was intercepted by military police apparently acting on a tipoff, the document was confiscated and the Australian had to write another version when he arrived back in London.

The 25-page letter was highly critical of the Dardanelles campaign that Murdoch labelled as “undoubtedly one of the most terrible chapters in our history”.

It was also circulated by British Prime Minister Henry Asquith and the ill-fated campaign was abandoned and all allied troops successfully withdrawn by January 1916.

Reports about the Gallipoli disaster and the carnage on the Western Front also contributed to the votes against conscription during the 1916 and 1917 plebiscites.

The Australian correspondent who spent most time on the frontline during the Great War was Charles Bean who defeated Murdoch for the job of official correspondent at Gallipoli.

Unfortunately much of Bean’s work was heavily censored and his best work came with the publication of his 12-volume Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-1918. His writing style also lacked colour and as a result it was Ashmead-Bartlett’s lively but inaccurate report of the Anzac landings at Gallipoli that was published first in Australia.

Australian photographer Frank Hurley’s extraordinary images of the Battle of the Somme are some of the most haunting ever taken. They capture the futility and destruction of trench warfare along with some of the humanity.

SPAIN AND WORLD WAR II

Arguably the most famous and influential of all combat photographers was the Hungarian born Andre Freidmann who adopted the pseudonym “Robert Capa”.

Capa’s 1936 image of a Spanish Loyalist soldier at the instant of his death during an attack in Cordoba is one of the most famous war pictures of all time.

Capa went on to document WW2 and his images from D-Day when he was on Omaha beach with American troops who faced some of the most fierce German resistance are some of the most gripping action shots of the war.

Robert Capa died in May 1954 when he stepped on a landmine in Vietnam while covering the French Indochina war.

The plight of the innocent victims of war — the women and children — was highlighted by the startling August 1937 image by H.S. Wong from “News of the Day” of a toddler sitting on the platform of Shanghai’s south station following a Japanese air raid. The child is badly injured and crying hysterically among the smoking ruins of the bombed station.

The chilling photograph and numerous others featuring the civilian victims of Japanese atrocities during the Sino-Japanese War showed the world what Japan’s version of total war looked like. They would also serve as a warning of what the Knights of Bushido had in store for the rest of the rest of Asia and the Pacific in the lead-up to World War Two.

The eyes and ears of the world would soon turn to Europe as Adolf Hitler’s Nazi storm troopers marched into Poland on September 1, 1939 to trigger the Second World War.

Britain joined the fray on September 3 and German forces using the new blitzkrieg strategy over ran Poland in just 27 days.

It would take 40 days for the Third Reich to occupy France and by the end of May 1940 it had pushed the allied forces into the sea at Dunkirk.

On May 25, 1940 the American journalist William Shirer wrote from Berlin, “German military circles here tonight put it flatly. They said the fate of the great Allied army bottled up in Flanders is sealed.”

Fortunately Hitler hesitated long enough to allow the Royal Navy and a vast flotilla of civilian vessels to rescue more than 330,000 men over 11 days. The role of the “little ships” featured widely in British propaganda and the term “Dunkirk Spirit” came to epitomise the stiff upper lift and the British ability to “Keep Calm and Carry On”.

It would take an act of bastardry on an epic scale on December 7, 1941 against an American naval based called Pearl Harbor to alter the course of the war by engaging and enraging the sleeping giant that had until then stayed out of the conflict.

Even though the censors prevented their publication for more than a year the graphic images of smoking US Battleships sinking at their wharves in Hawaii would stir the American people and the American war machine as it moved to drive the Japanese back to Tokyo island by island.

One of the most famous images of the Pacific War was “Raising the Flag” by US Marines on the island of Iwo Jima captured by Joe Rosenthal who was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for the shot taken on February 23, 1945.

Closer to home the Australian correspondents Chester Wilmot and Osmar White with photographer Damien Parer covered what has become known as the Battle for Australia along Papua New Guinea’s famed Kokoda Track.

Parer won an Academy Award for his cinematography and the three Australians were instrumental in having troops issued with mottled green camouflage uniforms when engaged in jungle warfare.

Parer was killed by Japanese machine gun fire while covering some of the most brutal fighting of the Pacific campaign on Peleliu Island in Palau in September 1944.

Their coverage of the Kokoda campaign was instrumental in showing the world that the mighty Japanese Imperial Army could be beaten at their own game in some of the harshest terrain on earth.

Wilmot, who had reported the siege of Tobruk, fell foul of the Australian commander General Sir Thomas Blamey for his strident criticism of the man he regarded as incompetent and his accreditation was revoked.

During both World Wars and the Korean campaign war correspondents were accredited by the military and subject to strict controls.

VIETNAM FREE-FOR-ALL

The Vietnam War changed all that and despite the best efforts of the dreaded “MACV” or Us Military Assistance Command, Vietnam reporters and photographers enjoyed virtually unfettered access to frontline units.

This was a blessing and a curse for commanders keen to show off their successes to audiences back at home but whose defeats, beamed into lounge rooms around the world, eventually shut down the war.

By 1968 there were 650 MACV accredited correspondents covering the Vietnam War. With US deaths climbing to 500 a month the Tet offensive and the My Lai massacre both took place in a year that was seen by many as the turning point for the US war effort.

Images of American and South Vietnamese strongholds under attack from North Vietnamese and Vietcong troops during January and February sent shock waves around the world and especially around the US and Australia.

The My Lai massacre occurred in March 1968 but was covered up until November 1969. When news broke that 100 American soldiers had murdered up to 500 civilians in cold blood, in possibly the worst war crime ever perpetrated by US forces, the public mood shifted dramatically against the war.

The terrible incident was made worse when three soldiers who had tried to protect civilians were labelled as traitors and shunned by their comrades.

The massacre, growing US casualties and images of terrified civilians combined with an increasingly vocal protest movement ensured that the war would become the most unpopular conflict ever fought by the US and her allies.

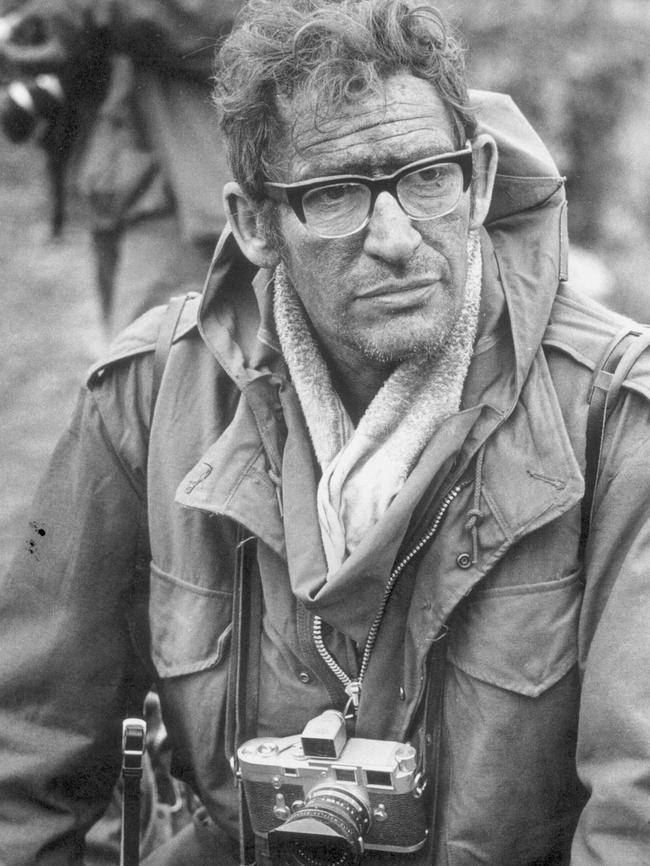

British-born photojournalist Larry Burrows covered Vietnam for nine years and he captured some of the most powerful images of the war including the defining picture of a young widow weeping over the bagged remains of her husband.

Australian cinematographer Neil Davis filmed incredible up close and personal battle scenes throughout the war only to die in a relatively benign coup on the streets of Bangkok on September 9, 1985 almost exactly 30 years ago. He even kept his camera rolling as he bled out.

When the 13-year Vietnam War ended in 1975 some 56,000 Americans had been killed along with countless millions of Vietnamese and 505 Australians.

It is not only images from war that prompt governments to act.

FAMINE, WARLORDS AND EAST TIMOR

Tragic pictures of the dead and dying from the 1993 famine in Somalia prompted a global response and shone a light onto the plight of citizens in a lawless state run by brutal warlords and their drug-addled gunmen armed with Mad Max-like Sport Utility Vehicle (carrying mounted anti-aircraft guns) known as “technicals”.

The stirring live pictures of US Marines storming ashore near Mogadishu provided a rare glimpse of how military power could be used for good as food supplies from the generous world response began to be delivered to the starving masses.

Mark Bowden’s excellent 1999 book “Black Hawk Down” and the later film version highlighted the dangers faced by soldiers when politicians decide to shift from humanitarian aid to regimen change.

East Timor in 1999 was Australia’s biggest military operation since Vietnam and it heralded the beginning of the most complex and demanding period in Australia’s modern military history.

It was media reporting about the activities of brutal militia groups backed by the Indonesian military that prompted Australia and the United Nations to take action to stem the violence and save thousands of lives.

The conflict bubbled along throughout the year with small numbers of correspondents from Australian media outlets reporting on atrocities being committed by militia thugs backed by the feared Indonesian Kopassus special-forces unit.

Following the brutal response (including ethnic cleansing) to a successful independence referendum on August 30, the UN and Australia established the INTERFET international force to quell the violence.

A small group of reporters including Lindsay Murdoch from The Age and Marie Colvin from London’s Sunday Times remained behind after the vote and it was their reports from inside the besieged UN compound in Dili that ensured a rapid response from the Australian military.

Colvin, like so many other courageous reporters before her, would later die in an air strike while reporting on the conflict in Syria.

The Iraq war of 2003 was the next big conflict for Australia and media outlets devoted huge resources to cover the American-led war.

EMBEDDING AND ASYMMETRIC WARFARE

This included the new concept of “embedding” with US military units where reporters were basically adopted by individual units and lived and worked alongside the troops.

In addition a large contingent moved to Baghdad to cover the war from the Iraqi side and about 100 of those remained in the city to report first hand on the “shock and awe” campaign.

As modern-day conflict has become less about conventional warfare and more about so-called “non-state” players and asymmetric warfare by terrorist groups such as IS or Daesh in Iraq and Syria the job of the correspondent has become more complicated and in many ways more dangerous.

Keith Murdoch and Charles Bean knew where the enemy was and could take steps to remain on the correct side of the danger line.

In Iraq and Syria today there is no line and correspondents face grave danger from fanatical fighters who have no respect for life or for the messengers who seek the truth.

Covering conflict is no longer about a journey to identify right and wrong or good and evil or observing the rules of war in the search for humanity, it is about shock and horror — and few if any are brave or foolish enough to die for the story.

Thirty-five Australian war correspondents have been killed in conflict. They are being honoured with the dedication of a War Correspondents Memorial at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra.

Originally published as From Keith Murdoch and Neil Davis to Marie Colvin, war correspondents can change the course of history