Flight Sergeant Clifton Wedd: a poignant letter to his mother, from the heart of a hero

In a 1942 letter, Flight Sergeant Clifton Wedd tried to explain to his mother the youthful desire that drove a generation of men to serve.

ANZAC Centenary

Don't miss out on the headlines from ANZAC Centenary. Followed categories will be added to My News.

THEY are words that would tug at any mother’s heart strings.

In a 1942 letter from Darwin after the Japanese bombings, Flight Sergeant Clifton Wedd tried to explain to his mother back home in Randwick the youthful desire that drove a generation of men to serve.

“My Dear Mother … I certainly do not find the thought of death a great terror that weighs on me,” he wrote.

“Life, in fact, it seems to me, is a quality rather than a quantity and there are certain moments of life whose value seems so great that to measure them by the clock … must seem trivial and utterly meaningless … their power is such that we cannot properly tell how long they last, for they colour the remainder of our lives.”

BODIES OF DIGGERS IDENTIFIED IN FRANCE

SPECIAL SECTION: THE ANZAC CENTENARY

YOUR FAVOURITE ANZAC PHOTOGRAPHS

SCROLL DOWN FOR THE FULL TRANSCRIPT

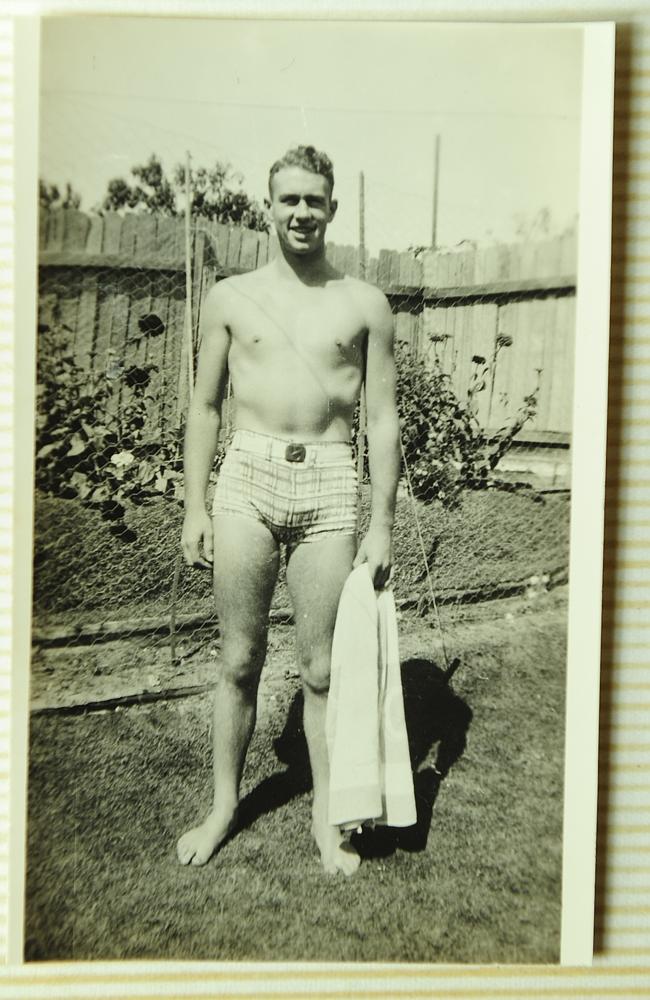

He was just 21 when he wrote this letter. Less than two years later he lost his life flying for the RAAF over the North Sea.

The soon to be unveiled Fallen Lifesavers Memorial at Randwick has unearthed stories of surf lifesavers who enlisted to serve and ultimately gave their lives for their country.

Flt Sgt Wedd will be one of thousands honoured when the memorial is unveiled on April 27 by Prime Minister Tony Abbott and NSW Governor Marie Bashir.

His sister Marcia, now aged 83, said she was still proud of the accomplished Coogee surf lifesaver who lost his life.

“He was a great all-round sportsman and he lived for the surf club, he was down there early every morning in his spare time,” she said.

“I certainly do not think that he was a war hero, just a young man prepared to fight for his country. I am proud of his efforts, he was a brave and lovely boy.”

According to Surf Lifesaving Australia, Flt Sgt Wedd was one of an estimated 7500 surf lifesavers to have served, from the Boer War to Afghanistan.

Flt Sgt Wedd was under the enlisting age of 21 years but Marcia remembers her brother’s eagerness to join up.

“He used to leave the form out for Mum and Dad every night. My parents didn’t want him to go but eventually my father signed,” she said.

“Our father fought at Gallipoli and he said there wasn’t enough luck to get two people from one family through war. It turned out he was right.”

Randwick Mayor Scott Nash said men like Flt Sgt Wedd shared a special quality: “The same reasons that drove them to become lifesavers also saw them sign up in their thousands to protect our nation. Sadly, many didn’t return.

“These are moments in time that changed the course of history for many. Moments that ensured the Australian surf lifesaver was an internationally respected icon. An icon that deserves our remembrance and our thanks.”

Surf Lifesaving Australia president Graham Ford explained what the memorial meant: “As I go around the country to different surf clubs, I see honour boards honouring all those who have served and those killed in action. This memorial has a national focus and is very strongly supported.”

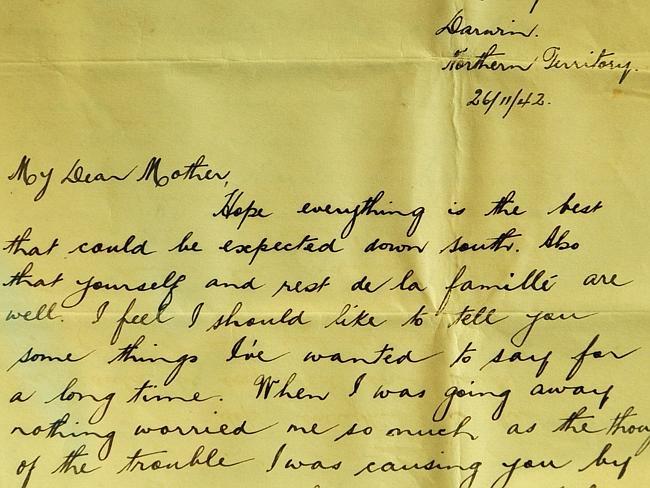

THE FULL TRANSCRIPT OF CLIFTON WEDD’S LETTER:

LAC Wedd

RAAF

‘T’ Group

Darwin, Northern Territory

26/11/42

My Dear Mother,

Hope everything is the best that could be expected down South. Also that yourself and rest of de la famille are well.

I feel I should like to tell you some things I’ve wanted to say for a long time.

When I was going away nothing worried me so much as the thought of the trouble I was causing you by going away, or might cause you if I were killed.

I certainly do not find the thought of death a great terror that weighs on me. I feel rather that, if I were killed, it would be you and those who love me that would have the real burden to bear, and I am writing this letter to explain why, after all, I do not think it should be regarded as such.

We make the division between life and death, as if it were, one of dates.

But just as we sleep half our lives, so when we’re awake we know that we are only half alive. Life, in fact, it seems to me, is a quality rather than a quantity, and there are certain moments of life whose value seems so great that to measure them by the clock, and find them to have lasted so many hours, minutes or seconds, as the case may be, must seem trivial and utterly meaningless.

Their power is such that we cannot properly tell how long they last, for they colour the remainder of our lives, and remain a source of strength and joy.

The first time I heard Brahms’ ‘Requiem,’ or, Enrico Carusoe singing ‘O Solo Mio’ remains with me as an instance of what I mean.

If such moments could be preserved and the rest strained off, as it were, no one could wish for anything better.

And just as these moments of joy may fill our own lives so, too, they may be prolonged in the experience of one’s friends and, exercising their power in those lives, may know a continual resurrection. I don’t think you will mind a personal illustration.

One of the ways I live in the truest sense is in the enjoyment of ‘sporting activities,’ and I would like to hope that my love of ‘sport’ might be for those who love and survive me more than a memory of something past, a power rather that can enhance for them the beauty of sport itself.

Or, again, we love Sydney, and I would hate to think that, if I died, the “associations,” that is, the College I attended, the baths and races therein, the club (surf) on the golf links, would make it “too painful” for you, as people sometimes say.

I would like to think rather that the joy I had in those places might not merely be remembered by you as a fact in the past, but transfused into you and give a new quality of happiness to your life there.

Will you at least try, should the unexpected come to pass, not to let the things I have loved cause your pain, but rather increased enjoyment because I have found such joy in them. In that way the joy I had can continue to live.

I cannot bear to think that, if I died, I should give you sorrow.

Your Ever Loving Son,

Clifton.