Twisted Minds podcast: Former detective sheds light on Childers backpacker hostel murders

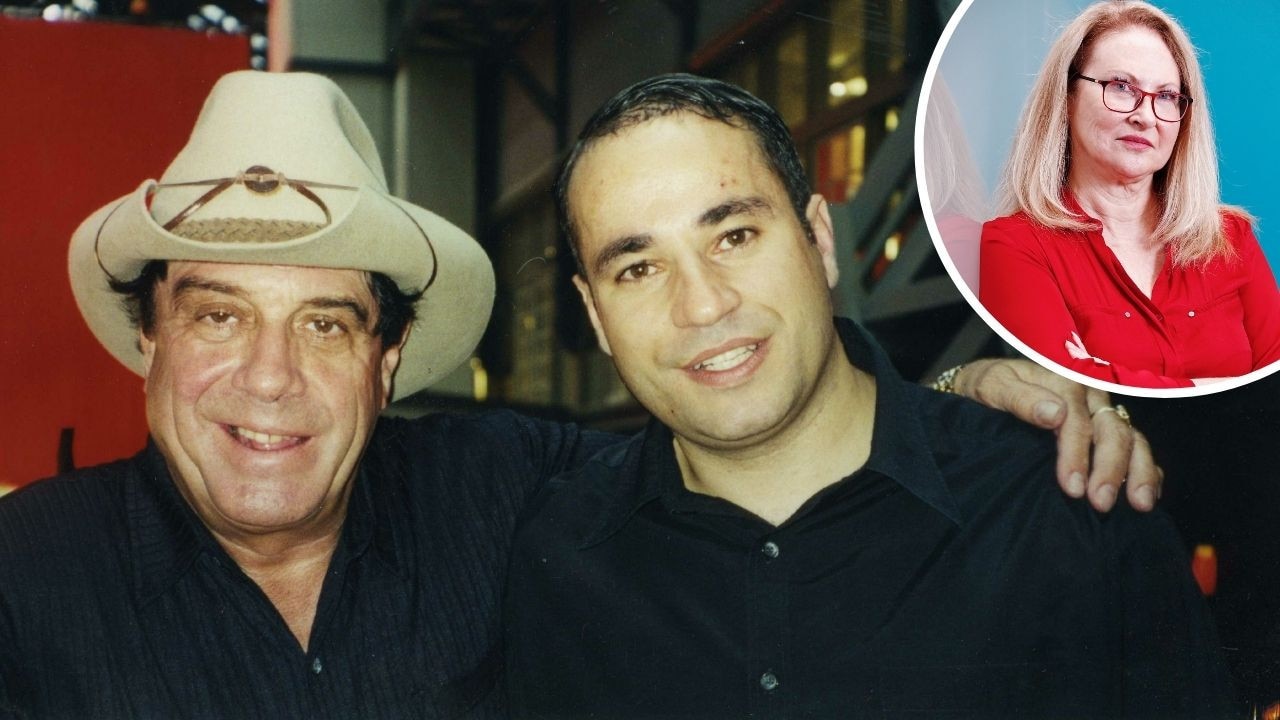

Former detective and criminal behaviourist, Steve Longford, reveals what he saw and knew of the arson attack on the Childers backpacker hostel and Bali bombing.

Twisted Minds

Don't miss out on the headlines from Twisted Minds. Followed categories will be added to My News.

How do you describe the smell of a dead body?

For former detective and criminal behaviourist, Steve Longford, the answer to that question varies.

“It depends how dead they are. There’s a difference between the smell of blood, just a blood scene, what that smells, like versus putrification or decay.

“The worst ones, when they come out of the water, or when stomach cavities are pierced or things like that, people will describe it differently. The same way someone will describe say, a wine differently.”

That Mr Longford likens the different aromas of death to the smelling notes of a fine wine is telling of just how many crime scenes he has witnessed and how analytical he is able to remain in the face of shocking violence.

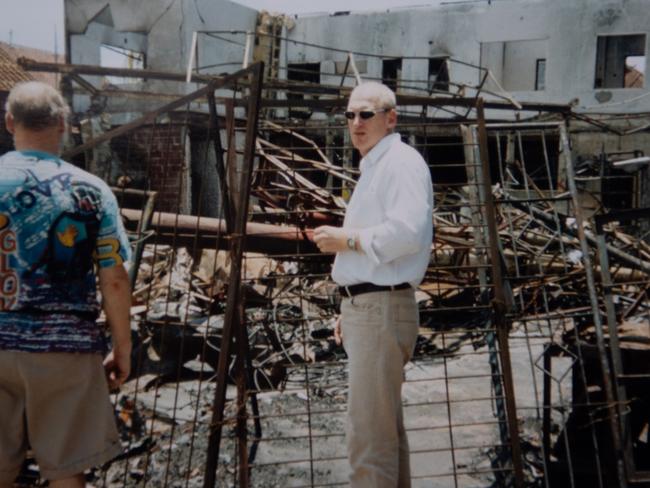

He walked through the smouldering remains left by the 2002 Bali bombings, in which 88 Australians were killed, and was one of the few to step inside the Childers’ Backpacker Hostel after it had been deliberately set alight in June, 2000, sending 15 young people to their deaths.

In both cases, his training in criminal behaviour analysis was called upon to help police catch the perpetrators.

In the case of the Bali bombings, Mr Longford quite quickly devised accurate theory that the perpetrators, later identified as foot soldiers of Jemaah Ismamiyah, were not criminal masterminds but disenfranchised locals.

“Everything’s black. It stinks. It’s that smoke smell and it’s the desolation,” he told the Twisted Minds podcast.

“There’s a dehumanisation of the victims with arson, which is a bit different to other scenes.

“It’s the same as when I was in the nightclubs in the Bali bombing after that, and we were trying to analyse the bomb shadows.

“That’s another good example of how completely humanised the whole scene was. It’s very difficult to try and understand the offender in terms of being a person rather than this really bad, bad [criminal].”

Learning his skills from the FBI, Mr Longford became a criminal behaviourist long before the profession was made cool by US TV shows like Mindhunter and cult-favourite Silence of the Lambs.

“I think it’s important to understand is that detectives don’t investigate crimes, they don’t investigate companies, they don’t investigate gangs – they investigate people. It always comes back to a person.

“And so what this discipline did was to recognise that we need to try and understand the behaviour of the individual when they’re in the crime scene, and understand what they were thinking when they were doing this sort of stuff. Because that will then point us in the right direction to go and look for the sorts of things that will help us to put a brief together, so we can put this person before the court or in some cases to catch them to start with,” he said.

In the case of the Bali bombings, Mr Longford quite quickly devised accurate theory that the perpetrators, later identified as foot soldiers of Jemaah Ismamiyah, were not criminal masterminds but disenfranchised locals.

“We watch a lot of homeland and TV shows where all terrorists are well trained, sophisticated, capable, have heaps of resources and execute their plans perfectly. And this one didn’t fit with that.

“They weren’t as successful as they could have been, luckily, because technically, they weren’t as good as they should have been,” he said.

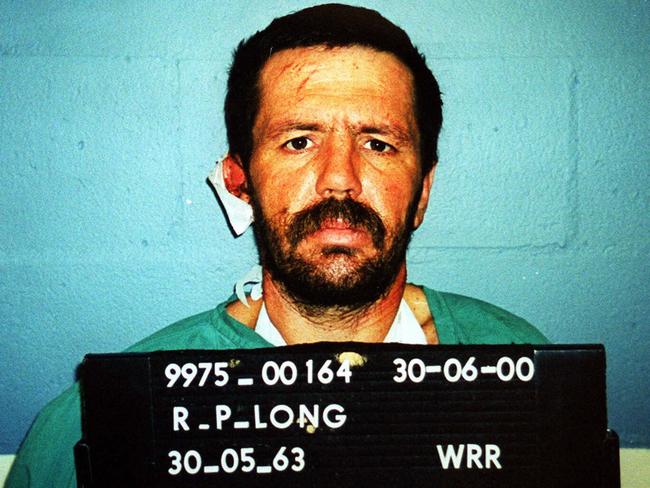

In the case of the Childers’ Backpacker Hostel, Mr Longford formed a theory about the perpetrator, fruit picker Robert Paul Long.

Long had expressed his hatred of backpackers and after being evicted from the hotel for rent arrears, told an English couple he was planning arson.

“There was some strong indications that one he wasn’t exactly the most likeable. He didn’t have the strongest personality or a lot of charisma, but he did like attention. And he had all these people in and around the hostile in the town that didn’t pay him much attention,” Mr Longford said.

He believes Long set the fire to gain attention and intended to save people to establish himself as a hero. However, once he lit the fire, it quickly swept out of control.

“When I went into that particular scene, there was still bodies and everyone near the door, which was locked, and near the window, which they couldn’t get out of.”

Mr Longford recalls walking through the blackened scene, straining to breathe in the air, thick with smoke and ash.

“The fire moved incredibly rapidly when we looked at the scene. There was some incredible crime scene remnants that I hadn’t seen before, in terms of how people responded to that situation that shows how fast it got out of control.

“I’m not saying that what happened wasn’t terrible. I’m saying maybe the motivation for why it started, and how it played out was not [Long’s] intent. We actually tried to incorporate that into the strategy down the track when he was on the run, to get him to come back in.”

Police did this by asking the media to run a narrative that the fire could have caused deaths accidentally, rather than painting the perpetrator as an arsonist murderer.

After five days on the run, Long was arrested in bushland, 32km from Childers. He was sentenced to life in prison in 2002 and became eligible for parole in June, 2020.