How Maddison lured police to planned killing ground

Police had been following Ricky Maddison for 20 minutes when he suddenly veered on to a side road. But something wasn’t sitting right. He wasn’t trying to evade them. Moments later, Senior Constable Brett Forte was dead. This is how the tragedy unfolded.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The 4WD was hidden in the dust from its tyres as it bumped along the ruts and ridges of Wallers Rd.

Behind, three police cars pursued Toowoomba’s most wanted at low speed.

They’d been following Ricky Maddison for about 20 minutes when he suddenly veered from the Warrego Hwy on to a side road, before taking them down the narrow, rough track.

But something wasn’t sitting right. Maddison was not trying to evade them.

Senior Constable Brett “Bretty” Forte, driving the lead vehicle, turned to his partner and said: “It’s like he’s leading us somewhere.”

“I just thought the exact same thing,” Senior Constable Cath Nielsen said.

In another part of town, Brett’s wife Susie, a specialist domestic violence officer who knew Maddison well, pulled her own police car to the side of the road. Her gut told her it was an ambush. She pulled out her phone and called her husband, twice. He didn’t answer.

Then, at 2.18pm on May 29, 2017, the police radio came to life.

“Automatic gunfire! Automatic gunfire!” an officer from Helidon yelled. “269 urgent! Automatic gunfire! A police car has rolled.”

That was the moment Senior Constable Susie Forte heard her husband had been murdered.

The search begins

The hunt for Maddison, a violent domestic violence offender, had begun in March.

He’d been to the home of his ex-partner to collect some belongings. They argued and he’d pulled out a handgun, firing a round into the air before pointing it at her.

In the weeks that followed, police from Toowoomba tried to find Maddison, including by running checks with Centrelink and Medicare. But Maddison, they believed, had gone “off grid”.

On March 27, police spotted Maddison on a camera they’d placed outside his ex’s house. Two days later, they got him on the phone.

They needed him to come into the station, an officer told him. Maddison refused.

Two weeks later, an arrest warrant was taken out by Brett Forte based on the evidence from the camera. Maddison was wanted for threatening his ex with a gun.

Days later, another arrest warrant was taken out after a decision was made to recommence proceedings against Maddison for an incident from two years earlier. It involved the same woman and serious allegations of torture and deprivation of liberty.

In May, Maddison contacted the woman via a payphone.

“Is it not enough that I’m broke and homeless and you want me to go to jail?” he said.

Sounds of gunfire

Nearby, police from Gatton had been running another investigation.

Locals had reported hearing a noise that sounded like a machine gun being fired in the bush, on the outskirts of Lockyer National Park.

Officers had thought them mistaken at first – until one resident produced a recording.

The noise was eventually isolated to a property on Wallers Rd, a bush block owned by the Byatt family. Police hid a camera by the gate.

Maddison, friends with Adam Byatt, had been staying in a makeshift hunting shed on the property. Byatt, unaware that Maddison was the target of a manhunt, had provided his unemployed and homeless mate with a mobile phone and somewhere to stay.

On May 18, Byatt stopped in to visit his mate. He told the inquest that on his way out, he spotted a man walking up the remote, dirt road.

Senior Constable Andre Thaler, tasked the day before with taking the lead on finding Maddison, would later tell an inquest he decided at random to drive along Wallers Rd, park by the Byatt property, and walk into the national park.

Constable Thaler said he had no idea Maddison was just metres away, and wouldn’t learn until later that Gatton police had been investigating reports of machine gun fire at the same property.

Byatt told the inquest he confronted Constable Thaler, who was on a day off and wearing civilian clothes but carrying his police QLite device, wanting to know what he was doing on the isolated road.

He told him to stay off his property and warned him to be careful, adding: “There’s hillbillies on these hills mate.”

Furious phone call

As the days went on, Maddison became more and more obsessed with the decision by police to reinstate the 2015 torture charges.

On May 24, he called the Toowoomba police station and asked to speak to the officer who conducted the original investigation.

Instead, Constable Nielsen took the call. He yelled at her. Punched the phone box. Told her police were harassing his family. He refused to hand himself in.

Two days later, Maddison discovered the camera by his front gate. Footage later recovered from the camera showed Maddison with a machine gun slung over his shoulder pulling it from its hiding place.

The confrontation

On May 29, Maddison went to see a friend in town. From there, he went to buy alcohol, discovering his bank account was near empty. He wrongly thought his pension had been cut – not realising it wasn’t due until the following day. This made him furious.

He returned to his friend, uncovering a cache of weapons on the back seat of his car.

“It’s only when I become big news (that) anyone will look at my case,” he said.

The friend suggested a trip to the Gold Coast.

“Nah, everything is already arranged,” Maddison said cryptically.

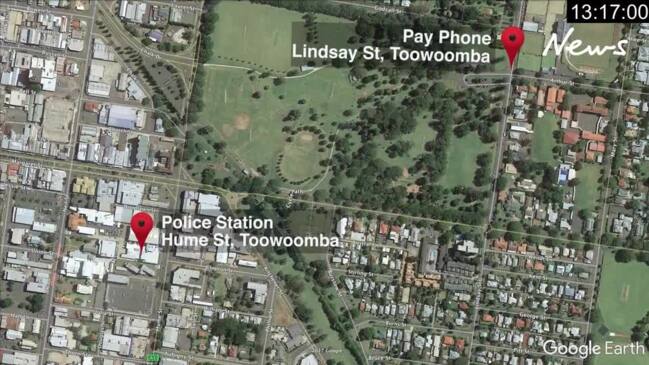

At 1.15pm, Maddison, standing in a public phone box in Toowoomba, called police. He ranted at Sergeant Peter Jenkins, repeatedly telling him to “come f**king get me. Stop playing games. Youse know where I am.”

The phone call lasted for more than half an hour. During that time, police in Toowoomba alerted the highly trained Brisbane-based Special Emergency Response Team they might be required if Maddison were found.

One minute after Maddison finally hung up the phone, a police patrol spotted his Nissan Navara pulling away from the kerb. What followed was a lengthy low-speed pursuit out of Toowoomba and down the range. Maddison drove at or even under the speed limit, with a convoy of police cars in his wake.

Then, he pulled off the Warrego Highway and on to a side road, before leading the convoy on to the unsealed Wallers Rd.

They followed Maddison up a rise, then, as the dust cleared, there he was.

Standing beside the driver’s door, Maddison raised his machine gun and opened fire.

Brett Forte, hit in the groin and arm, reversed his car in a dying effort to get he and Constable Nielsen to safety.

It hit the embankment and rolled, coming to rest on its side.

Constable Nielsen drew her gun and fired at Maddison through the windscreen.

She freed herself from the vehicle and began smashing the windscreen from the outside. Another officer joined her. It took a long time to smash a hole large enough to pull the unconscious Brett from the car, all the while hearing bursts from the nearby machine gun.

They pulled him into one of the other police cars and drove him to safety, where two officers performed CPR. But Brett’s injuries were too great. A LifeFlight doctor pronounced him dead on scene at 3.29pm.

Overhead, the police helicopter had found Maddison back at the hunting cabin. By 5pm, SERT was attempting to negotiate with the gunman.

Maddison, fuelled by meth and paranoia, fired into the air and into the bush.

Nearby was the heavily armoured BearCat. The BombCat would also be brought on scene, with the bomb squad robot sent in to puncture the tyres of Maddison’s Navara.

Over the following hours, negotiators made 85 attempts at convincing Maddison to surrender.

At 11.04am, Maddison emerged from the cabin and pointed his machine gun at a SERT 4WD, two officers seated inside.

He emptied the entire magazine. A SERT operative outside the vehicle fired back. Another fired from the turret of the BombCat.

Maddison, hit, ran into the tree line. Lying on his back among the trees, he changed the magazine, a second automatic rifle slung over his shoulder.

Back on his feet, he raised his gun and ran at two snipers. They both fired. Maddison took a hit to the chest.

Hero’s farewell

Thousands of police formed a guard of honour, stretching along Toowoomba streets for more than a kilometre, to farewell their fallen colleague. Brett, a father of three, was posthumously given the Queensland Police Valour Award – the highest honour the service has to recognise an act of bravery.

Recriminations

As the weeks wore on, both Susie and Constable Nielsen began to ask questions about how much their colleagues had known about Wallers Rd.

Would things have turned out differently had they known about the many reports of automatic gunfire coming from the very property Maddison had taken them to that day?

An inquest into Brett’s death would later hear the women were met with hostility from their own colleagues when they queried what had unfolded and if Brett’s death could have been prevented.

Constable Nielsen said she was lied to about what fellow officers knew about the automatic gunfire reports.

“My time (at work) in July and August was terrible,” she told the inquest. “I don’t know how I didn’t unravel. I’m being threatened with a 466 (complaint form). I didn’t know what world I was in.”

The inquest also heard allegations that Susie was “blamed” for Brett’s death by her fellow officers.

After these claims were made, complaints were lodged against both women by ESC Detective Senior Sergeant Fiona Hinshelwood. They were accused of failing to report misconduct and perjury.

The complaints were ultimately dismissed by the ESC.

When Susie tried to address the inquest with a victim impact statement it was refused in its full form, with a non-publication order made.

She was instead asked to write a watered down “family impact statement”.

Call for change

Susie and Constable Nielsen remain in the service in the same district where the tragedy unfolded.

Susie is a general duties officer who still does a lot of work with victims of domestic violence. Constable Nielsen told the inquest she was proud to be a police officer despite the toxic culture.

“Brett Forte’s death cannot be in vain,” she said.

“We have to change cultures, because this cannot happen again.”