Men’s helpline call, chilling Bunnings footage played at Hannah Clarke inquest

The Hannah Clarke inquest has seen chilling footage of her killer Rowan Baxter shopping for the tools he would use to kill his family and played a call he made to a men’s helpline.

Police & Courts

Don't miss out on the headlines from Police & Courts. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The Hannah Clarke inquest has been told a psychologist gave estranged husband Rowan Baxter a “glowing endorsement” five days before he penned a death note, and has viewed footage of him shopping for the tools he would use to kill his family.

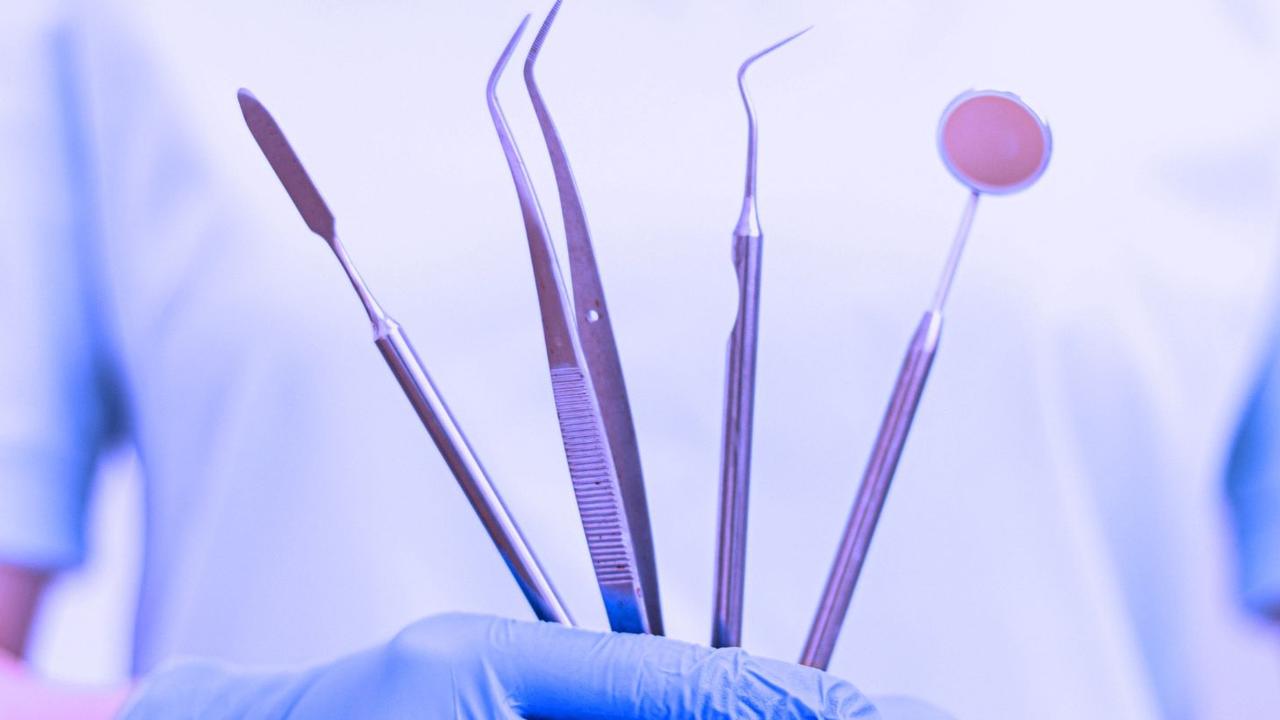

BAXTER SHOWN SHOPPING FOR MURDER TOOLS

A singlet-and-shorts-clad Baxter could be seen walking slowly down the mowing aisle of the Mansfield store, looking at different jerry cans and picking one up before deciding on a 5l green plastic container.

The footage showed Baxter approach the checkout with the fuel can, plastic zip ties and a container of surface cleaner.

The shopping trip took place at 6pm on February 17 – two days before he murdered Hannah, Aaliyah, 6, Laianah, 4, and Trey, 3.

SEE THE VIDEO ABOVE

The following morning, Baxter visited the Caltex service station at Carindale and purchased 4.6l of fuel and, shockingly, lollies, including three Kinder Surprises – presumably for his children.

Also played to the court was a phone call Baxter made to a men’s helpline just after 4pm on February 18, the day before he killed his entire family.

In it, an upbeat Baxter joking and laughing with the operator says he is calling looking for access to a men’s behavioural change program, saying he is only doing it to help himself in court.

“It’s not my idea but apparently I have to do it,” Baxter says.

He explained he didn’t think that as a 42-year-old he’d have to work on his behaviour “but apparently I have to because it’s going to help me out apparently”.

Baxter proceeds to blame Hannah for the situation, saying “my wife put a DVO on me”.

“ … And it’s a bit of, to be honest it’s almost like a game to put her in a better position for family court and unfortunately I’ve been roped into it and now this temporary DVO is hanging over my head,” he said.

“Well I just think it’s going to put me in a better position because she’s trying to do all sorts of things to get me to breach it and do this and that and it’s getting to the stage where I need to wear a spycam on me 24/7 because I just can’t trust her.”

Baxter asks the operator if taking the course means that he is guilty and is assured it is not an admission of guilt.

“She was saying I’m guilty if I do this…” he says.

“I sort of understand it but I don’t because I’m not the one that has the problem but I guess I’m just doing what I’m told.”

He tells the operator he is 42 and the pair chat about Baxter’s New Zealand upbringing and how he moved to Australia when he was about 28.

He explains how he met a “lovely lady”, being Hannah, and they had some children and “unfortunately it’s gone sour in the last few months”.

“I’ve been put through the ringer in the past few months….” he says.

He explains that they ran a gym together and had three children aged 6, 4 and 3, and claims their relationship deteriorated because Hannah started to have feelings for another member at the gym “behind my back”.

The inquest had previously heard there was no evidence of that, and Baxter repeatedly accused her of cheating and blamed infidelity in a previous relationship for his jealousy.

“I’m 42 I shouldn’t have to ask for my kids,” he said.

“It’s got to the stage she was dictating when I could see them.”

Baxter says Hannah, whose age he can’t remember, guessing 30 and 32, “became very immature”.

He paints a flattering picture of his abduction of Laianah, claiming the little girl had wanted to go with him and that “the mother kicked up a stink”.

“It’s gotten worse and worse and worse,” he said.

“I can’t even tell you how much my life has turned around in five minutes.

“It’s very, very, very scary.

“I never ever ever thought my wife was capable of doing anything like this.”

The man on the phone provided Baxter with the phone numbers of two support services that offered courses in anger management and behavioural change.

The inquest heard Baxter called one of the services at 4.41pm on February 18 but the lines were all busy.

The service had a 24-hour callback service and Baxter’s call was returned the next day at 12.01pm.

But by then, Baxter was already dead, his children had been murdered and Hannah was fighting for her life. She would die later that day.

“The one in Logan is open until 5pm,” the call taker said.

“Fantastic, thanks,” Baxter replied.

The inquest heard later that night, Baxter facetimed with his children “and all he did was sob”.

TIMELINE OF BAXTER’S LAST DAYS

February 17, 2020: Hannah successfully applies in the Queensland Civil and Administrative Tribunal to have her name removed from the lease of the home she shared with Baxter. He is informed he is now solely responsible for the rent. That same day he is informed his rent is in arrears and he borrows $1000 from a friend to “clear his debts”.

February 17, 6.07pm: Baxter visits the Mansfield Bunnings where he selects the items he will later use to kill his family. His purchases include a jerry can and zip ties.

February 18, 4.17pm: Baxter calls men’s helpline asking for referral to behavioural change and anger management courses.

February 18, 4.41pm: Baxter calls the service recommended in the previous call, however all operators are busy and he leaves a message for them to call back.

February 18, 7.24am: Baxter goes to the Caltex at Carindale where he fills the Bunnings jerry can with fuel and purchases lollies and chocolates.

February 18, evening: Baxter has a video call with his children and sobs the entire time. Hannah later messages friends telling them about Baxter’s distress and expresses her sorrow about how things could have been different and how she feels sorry for him.

February 19, 8.30am: Baxter ambushes Hannah as she leaves her parents’ place to take the children to school. He orders her to drive, dousing her and the children with fuel and lighting them on fire.

February 19, 12.01pm: Hours after Baxter kills his family, the men’s helpline returns the call he placed the night before.

PSYCHOLOGIST GRILLED OVER DOCUMENTS

A psychologist who treated Rowan Baxter in the lead-up to him murdering his family has been grilled on why she did not hand over all of her paperwork to police when they served her with a search warrant.

The inquest into the deaths of Hannah Clarke and her three children heard Vivian Jarrett had treated Baxter for six sessions, compiling a “score” at the end of each session.

But counsel assisting the coroner Jacoba Brasch asked Ms Jarrett why she had not handed over the documents relating to one of the sessions and only compiled a score for another this morning – two years on.

“When the search warrant was executed, you didn’t think, ‘Heavens, I’m missing a session’?” Dr Brasch asked.

“You understand, don’t you ma’am, that a search warrant is a serious and solemn obligation … and not one that you pick and choose.”

Ms Jarrett said she did not think one of the documents was relevant.

Dr Brasch asked why she would not think reports on psychological sessions with a man who went on to kill his wife and three children would be relevant.

“In my mind I had gone through and given you everything I had,” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch questioned why the psychologist had not printed the notes relating to her second, third and fourth sessions with Baxter.

“It has not crossed my mind to print the results,” she said.

Coroner Jane Bentley told her: “That’s not making any sense to me.”

“How could it not cross your mind when you’ve printed first of all one of them, now another two, but you didn’t think to print the rest of them. Is that what your evidence is?”

“I didn’t think to print off the scoring because I had it written down,” Ms Jarrett said.

“I apologise. I did not think to print them.”

Dr Brasch told the psychologist she “obviously didn’t think to produce (sessions) 2, 3, 4, 5, or 6 to police in the days after the horrific events”.

Ms Jarrett agreed that it was ordinarily the habit of psychologists to make notes as they go along with patients but said she typed up the notes after her appointments with Baxter.

“Can I say to you though they read as if you’ve sat down and produced the notes after the fact,” Dr Brasch put to her.

“I can’t help that that reads that way,” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch pointed out that in one of the notes, Ms Jarrett is “giving conclusions as at 20 February”, the day after Baxter murdered his family.

“Yes I added in some thoughts that I had at the time and obviously that was after,” she said.

Ms Jarrett said her appointments with clients went for 50 minutes and she used the 10 minutes before her next patient arrived to type up notes from memory.

“I type pretty fast, yep,” she said.

When asked why she didn’t take handwritten notes throughout the session: Ms Jarrett said: “I just decided to type my notes, I don’t know how to answer this any other way.”

The psychologist agreed that issues Baxter presented with including jealousy, controlling behaviours and separation were “high risk” indicators of potential harm to others.

“What did you think he was coming to see you for?” Dr Brasch asked.

Ms Jarrett said Baxter’s GP had written a mental health plan that referred him to a psychologist.

Dr Brasch asked why the word “habit” had been used to describe Baxter’s controlling behaviour over his wife.

“Habit? We’re talking harm aren’t we?” she said.

“We are talking separation, control, jealousy. You would accept wouldn’t you, that controlling behaviour, jealousy, separation … they’re not just habits, are they?

“They’re risk factors.”

Dr Brasch suggested the psychologist should have paid more attention to the risk Baxter posed to others.

“Surely there’s a wider obligation to ensure he is not a risk to someone,” Dr Brasch said.

Ms Jarrett said she was aware that when Baxter first came to see her, he was the subject of a temporary protection order.

She agreed that she had not seen the order, nor had she asked for it.

“Were you aware of the conditions?” Dr Brasch said.

“No,” Ms Jarrett said.

“Did you ask him about it?”

“I’m just trying to think…” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch put to Ms Jarrett that she held herself out on her website as an expert in domestic and family violence.

She responded that she had “expertise” in that area, not that she was an “expert”.

“Do you have any familiarity with the concept of coercive control, really?” Dr Brasch asked.

“Yes,” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch put to her that in which case, she should understand one of the critical factors in coercive control was respondents doing “image management” where they presented themselves in a positive light.

Mr Jarrett agreed she did know.

“Why has it taken ten minutes to get to that point, I asked you that rather basic question some time ago,” Dr Brasch asked.

“I think it’s the direction with which you’re saying….”.

Coroner Jane Bentley interjected to confirm Ms Jarrett understood she was under oath and the consequences of not telling the truth while under oath.

Dr Brasch repeatedly questioned where in the psychologist’s notes she mentioned that Baxter was engaging in image management.

“I have not noted that in my notes,” she said.

Ms Jarrett agreed with Dr Brasch that during her sessions, she did consider that Baxter may have been using her or “pulling the wool” over her eyes in order to get “good evidence” for family court proceedings.

“Where’s that in your notes?” Dr Brasch asked.

“It’s not,” Ms Jarrett said.

“It would be a usual thing you think one thousand things in a session but you don’t document every single thing,” she said.

“I did not document it. I did not say I didn’t think it was important.”

Dr Brasch said Ms Jarrett had written a “glowing letter” for Baxter four weeks before he murdered his family where she described him as doing “remarkably well” despite his wife leaving him.

“Mr Baxter has been distressed over his wife leaving him suddenly but has been coping remarkably well considering,” Dr Brasch read from the letter.

Dr Brasch asked why she would write such a letter given her admission before the inquest that Baxter was likely using her for “image management” and to get favourable evidence for Family Court proceedings.

The court heard Ms Jarrett’s letter included the comment: “I have no concerns regarding his mental health.”

“You know Baxter wanted this to response to his wife so he could see his children,” Dr Brasch said.

“I did not have any evidence in front of me to say he was an unfit parent,” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch repeated Ms Jarrett had given evidence that she believed Baxter could be using her for “image control” and had agreed there were red flags in the relationship, including controlling behaviour.

The court heard the letter finished with: “All seems in order for him to regain contact (with his children).”

“(You didn’t) actually think through what you’re committing to writing there,” Dr Brasch said.

“I am aware there is a domestic violence order in play … I’m aware that I’m not the only person involved in this,” Ms Jarrett said.

“Ma’am, you’re the only person writing this letter,” Dr Brasch interrupted.

“The opinions you’ve reached there are formed on what this bloke has told you … on his say so, even though you’ve got all the concerns you’ve given under oath before.”

“At that point in time, that is what I was thinking,” Ms Jarrett said.

Dr Brasch said: “A mere five days after – can I call it a glowing endorsement of this man … he started penning what we can call a death note.”

Dr Brasch asked how Ms Jarrett could reconcile that letter with the evidence she had given that she was aware of the risk factors.

“When he presented in the beginning he wasn’t coping remarkably well,” Ms Jarrett said.

“He was distressed. There was improvement over time.”

Dr Brasch put to Ms Jarrett that Baxter had presented an image to her that she “accepted without question” but she denied that was the case.

The court heard in her notes, Ms Jarrett said Baxter had been “very open and sincere in our sessions”.

She said that on the day she wrote the letter, she had no concerns about Baxter’s mental health.

Dr Brasch told the court Ms Jarrett had described Baxter in a statement to police as “level-headed” and “low-risk”.

She asked Ms Jarrett to accept that the first time she had any concerns about Baxter was “sitting here now in the witness box”.

“I have those thoughts all the time; (it) doesn’t mean I write them down,” Ms Jarrett said.

“The risks are not noted in my notes and they were not noted in the GP’s plan.”

“Sorry, I’m not interested in the GP’s plan,” Dr Brasch replied.

The court heard that on December 20, at Baxter’s first session, they discussed helping him “feel calm” and “less distressed” and Ms Jarrett gave him some breathing exercises.

After repeatedly asking questions about where to find evidence of concerns in Ms Jarrett’s notes, which she did not answer, the coroner asked Dr Brasch if there was a point in continuing with the witness.

“I’m wondering if we’re getting anywhere with this witness; she’s not answering questions,” deputy state coroner Jane Bentley said.

Dr Brasch agreed, telling the coroner: “I think I’ve got more than enough to make my submissions.”

The court heard in a session on December 31, 2019, Baxter speaks about his sexual jealousy.

Dr Brasch put to Ms Jarrett that the disclosure should have raised another red flag but said there was no mention of it in her notes.

“I have not documented the concern in the words of sexual jealousy,” Ms Jarrett said.

The court heard Ms Jarrett described Baxter in her affidavit as “very level headed”.

The court heard there was also no concern in her notes about the idea of forced sex despite Baxter’s disclosures and it being another risk factor he displayed.

Coroner Bentley asked Ms Jarrett if she was concerned about Baxter’s marked improvement of his mental state in his self-assessment forms, despite disclosing things were going worse for him in his personal life.

“What I’m asking is did you think that huge improvement over 11 days when he’s telling you things were getting worse for him seemed to be unrealistic, did you think about it at all” Coroner Bentley asked.

Ms Jarrett said she did think about it and when asked what went through her mind, she said: “to question it”.

Ms Jarrett repeatedly told the court it was her practice to write up her notes immediately after her sessions.

But Dr Brasch questioned whether she wanted to review that evidence after revealing a discrepancy in dates.

“We know from your entries that you had a session with Mr Baxter on 21 January 2020 and we’ve got your 21 January session notes … (they say) ‘he says mediation was really stressful et cetera’…,” Dr Brasch said.

“I’m not going to ask you about the content of it other than to confirm like you gave evidence before you typed it out immediately after the session on the 21st?”

“Yes, yep,” Ms Jarrett replies.

“Ma’am the mediation was the 23rd,” Dr Brasch said.

“Do you want to review the idea that you wrote the notes after every session?”

Ms Jarrett replied: “I don’t know why he would have said that. I don’t know when the actual mediation was….”

Dr Brasch again asked if Ms Jarrett wanted to review her evidence that she wrote the notes immediately after her sessions.

“My question is simply this – you’ve told us every single tome you’ve typed your notes up immediately after, you’ve typed up notes on the 21st of January about a meeting that actually happens two days down the track – do you want to review you evidence?” she asked.

“I stick by it because that’s just what happened.”

THE LETTER IN FULL

21 January 2020

To whom it may concern

Mr Baxter has seen me for six sessions.

Mr Baxter attended the first session prior to his partner officially separating from him on the 20th of December, 2019.

Mr Baxter has been stressed over his wife leaving him suddenly but has been coping remarkably well given the situation.

He has been very open and sincere in our sessions. I have no concerns regarding his mental health.

Contact with his children would be ideal and after reviewing his parenting strategies, all seems in order for him to regain contact.

Yours sincerely

Vivian Jarrett

Note: The court was told the date of separation cited by Ms Jarrett in this letter was incorrect. The correct date was December 5.

WALKING ON EGGSHELLS: COERCIVE CONTROL EXPLAINED

Expert witness Heather Douglas explained to the inquest the different forms of coercive control.

She said it is often targeted to the particular victim and victims often describe having to “walk on eggshells”.

Professor Douglas agreed non-lethal strangulation was a very high-risk behaviour.

“Strangulation is very much used as a tool of control … to make them think you could kill them just by squeezing their throat,” she said.

Prof Douglas said police needed to have more regular training around domestic violence and coercive control.

“I think that is clearly a concern,” she said.

“And there are examples which show there just simply isn’t sufficient training for police … we know that.”

Prof Douglas said in the case of Hannah Clarke, she believed if police had spoken to her more, they could have made the decision to charge Baxter with stalking.

“I don’t see why that wasn’t a possibility to investigate here,” she said.

She said if police had asked the right questions, Hannah might also have disclosed the incident of non-lethal strangulation.

Prof Douglas said she has studied many successful prosecutions of non-lethal strangulation where there wasn’t necessarily physical evidence of injuries.

She said police often “jumped too quickly” to putting in place a temporary protection order and don’t investigate further.

She said she would support a trial of a multidisciplinary police station with highly trained police working alongside professionals in the areas of health, housing, educational and child protection.

“I think we need to have trials … I think that’s potentially a good idea,” Prof Douglas said.

“The problems we had in this particular context might not be solved by that.

“There’s a lot that went wrong that might still go wrong in that context.”

HANNAH HAD BEEN STRANGLED DURING SEX

Earlier, a domestic violence support worker has detailed how she hadn’t shared with police that her husband Rowan Baxter had strangled Hannah Clarke during sex.

Domestic violence support workers who assisted Hannah when she left Baxter are giving evidence at an inquest into her death today.

The Brisbane Domestic Violence Service worker, who cannot be identified, spoke with Hannah when she engaged the service on December 9, 2019.

The inquest heard the support worker, in her risk assessment form, detailed how Baxter had strangled Hannah during sex in November.

The form said Baxter had “put his hands around Hannah’s neck during sex without her consent and would not remove them”.

Asked why she hadn’t shared that information with police, the support worker said “most women” she did risk assessments for had been strangled by their partner.

“So unfortunately, this sort of information wouldn’t be something I’d usually share with police,” she said.

“I knew Hannah had been in regular contact with police. I think this information would have been information I assumed that the police would know as well.”

The inquest has heard Hannah had not told police about Baxter choking her and that nonlethal strangulation was a strong indicator she was at extreme risk.

“Again I think it really depends on the situation and I’m just making an assumption here … sometimes in those sort of situations where it’s sexual and there hasn’t been any pressure used, they might not consider that strangulation,” the support worker said.

She said in another recent case, where a young person had choked their mother, “nothing was done” by police.

“Unfortunately DV services and police aren’t always as linked in as we would want them to be,” the support worker said.

She said she has had “mixed experiences” with police and it depended on the individual officer.

“Sometimes I’ve had police that have been able to respond really well and go above and beyond,” she said.

“But other times I’ve had experiences where I’ve had to advocate and unfortunately a breach hasn’t been taken seriously.

“I’ve had experiences where it hasn’t been so great.”

She said in cases where a matter needed to be referred to the police high risk team, she would consult with her colleagues before going ahead.

The support worker earlier told the court she took about six weeks to complete a Risk and Safety Assessment (RASA) – not a week as she would have hoped – due to the large workload of other victims needing the support service.

“So in that situation I believe I had completed the risk and safety assessment with Hannah and it was pending allocation to a case manager,” she said.

“Hannah had reached out with some concerns with the respondent using technology abuse and I was able to provide that bit of case management before she was allocated her actual case manager.”

The BDVS worker said at any time, the service had a “huge backlist of women needing support” with calls for immediate crisis response often coming in which is why it took longer than anticipated to complete Hannah’s RASA.

“We get a range of high risk situations, we might get a call where someone has been strangled that day and the RASA needs to be completed so unfortunately I think it was a situation where we didn’t have the manpower to complete it in that week when I initially wanted to complete it,” she said.

The social worker said when she started at the service, she received a handover from the person whose role she was taking over but there had been no specific training for the role.

She said there was no training about information sharing with police or about lethality indicators in cases where an aggrieved person expressed a fear of death at the hands of perpetrators.

The court heard in Hannah’s case, the support worker specifically highlighted the instance of Baxter choking her in case notes because she felt it was an important issue for others on her case to know about.

Asked whether she was aware of any situations where the RASA was given to police or the vulnerable person unit, she said: “I know that it does happen but I can’t remember any cases of mine where that might have happened.”

She agreed with questioning that many women who contact the service for support had “difficulty” getting police to lay criminal charges against perpetrators.

DV support worker reveals ‘huge red flag’ in Hannah case

The second domestic violence support worker to give evidence was embedded with the police Vulnerable Persons Unit at the time Hannah was seeking help.

The worker agreed that if a victim disclosed an incident of nonlethal strangulation, it would be important to pass that information onto police.

She said on January 8, 2020, she went with two police officers for a “short visit” of about 25 minutes to see Hannah.

“So my role in this particular instance was to follow up with Hannah to see if she required any wrap around support, ongoing support … whatever that might be,” she said.

“She did indicate that she would like to have support or be linked in with, I guess, a family law lawyer and counselling.”

The worker said she didn’t know a lot about Hannah’s case at that point.

“Just the fact that her estranged husband had taken, abducted, the middle child, which alerted us. I mean, that’s a huge red flag,” she said.

“It’s not normal behaviour … it’s just, who does that?”

The worker said she would generally be handed a job sheet when accompanying police to visit a victim of domestic violence.

She said she would cross reference the job sheet with any referrals they might have on their own system.

The worker said the purpose of their visit was to obtain more information and more detail so they could determine how they could help.

Asked why a risk assessment completed in January by the domestic violence service had not shared with police Hannah’s disclosure that Baxter had strangled her, the worker said she did not know.

“It should, absolutely,” she said.

The worker said when she went with members of the police Vulnerable Persons Unit on January 8 to visit Hannah, about two weeks after Baxter abducted Laianah, she was “surprised” by how calm Hannah was.

“I just naturally assumed … she would be more I guess fearful, more emotionally distraught, but having said that her children were also present when we visited,” she said.

“Maybe she didn’t want to display that kind of emotion with her children.”

The worker accepted that the lack of distress displayed by Hannah could have been due to the fact she and the VPU officers were strangers and that she could have been trying to shield the children.

The social worker said in January, she went on leave and Hannah’s case was not passed onto someone else because “we would only hand over matters of great concern”.

“If we assessed an aggrieved was at imminent risk in our absence if we were on annual leave we would hand it over to another case worker but there were no real, I didn’t believe Hannah was at imminent risk because the police were involved, we were involved, I know she had left her estranged husband, I didn’t realise she was living with her parents but I did know her parents were there as a social support.

“There was nothing glaring for me that I could assess her as being at imminent risk.”

The court heard not long after that visit, the Vulnerable Persons Unit closed off Hannah’s case in mid-January, one month before Baxter killed her and the children.

She gave evidence that when the VPU closes off a case, the embedded worker still has a role in helping the aggrieved access appropriate support including counselling and housing.

“I didn’t really have a lot of intensive engagement with her which is why after my annual leave I put in a follow up action to touch base with her to try again to discuss what her support needs were,” the worker said.

“And that’s when you discovered what happened,” Dr Brasch asked, referring to Hannah’s murder.

‘System was working’: DV support worker

The third domestic violence support worker said she was a case manager at the time the service was helping Hannah.

She said she phoned Hannah on January 29 and they met on February 4.

“I can recall that she was upbeat, she was looking forward to sort of moving on with her life,” the worker said.

“She was very forward focused.”

She said Hannah later told her about the incident where Baxter had twisted her arm after arriving at her parents house with intimate photographs of her spread across the back seat of the car.

She agreed it was an escalation of Baxter’s behaviour and as a result, they put together a new safety plan for her.

One of the recommendations was that Sue and Lloyd Clarke collect the children from school instead of Hannah.

She said no plan was put in place to put Hannah into emergency accommodation for her safety.

“What I keep in mind in this situation was that Hannah identified that she was feeling supported living with her family and that’s where she felt best,” she said.

The worker said she did not consider referring Hannah to the police high risk team.

“In Hannah’s scenario, yes, there was absolutely a risk, and a high risk there – and I don’t deny that,” she said.

“But the system was working as it should have been.

She said there wasn’t a “break down” where Hannah could have “fallen through the cracks” and that was what the high risk team was for.

The worker said generally speaking, the risk assessment completed by the domestic violence service would not be shared with police.

The worker said in her experience it was “difficult” to get police to bring criminal charges in domestic violence matters and agreed it was easier to encourage them to pursue a domestic violence order breach instead.

“In my experience, yes, I believe QPS might see that as a better pathway to getting some sort of charge rather than pursuing a separate criminal offence,” she said.

The worker agreed that Hannah would not have understood the seriousness of strangulation as an indicator of potential lethality.

When asked whether she or anyone else could have explained that to Hannah and encouraged her to tell police, she said it was “very contextual” and on a case-by-case basis.

“In my experience you can’t just have that conversation with a woman in your first engagement with them because they’re never going to engage with the service again because they’re only just coming to terms with the fact they’re a victim of domestic and family violence and if you’re going full on into a conversation about how serious this matter is and you need to go to police right there, then you’re going to lose them, they’re not going to engage again,” she said.

“So it’s a very delicate process and it takes a lot of time and consideration, it’s not something that can happen in the first conversation.”

Counsel for the Clarke family Kylie Hillard pointed out by that point in time, Hannah had “lots of conversations” and “multiple contacts” with the service and a rapport had been established.

“I mean yes, but in saying that, that time frame is very short, if you look at the time she actually engaged with BDVS versus when her death occurred, we’re looking at just over a month, just a little bit longer,” she said.

“That’s not a lot of time to establish a rapport with someone who you’re going to have these difficult conversations with,” she said.

Ms Hillard put to the worker that she had given evidence Hannah was future-focused and upbeat and not presenting in a particularly vulnerable way.

The worker said she could not comment on a suggestion that the conversation could have been raised with Hannah as part of safety planning.

The court heard that a victim’s fear of death is a significant risk factor in domestic violence homicides and despite Hannah disclosing that fear to others, no one from the service asked her about that.

The worker said there was no checklist to ensure victims were being asked about issues including their fear of death and claimed it would be too “clinical and formal” if staff had to ask specific questions.

“It’s meant to be a conversation, it’s meant to be a narrative, and it’s meant to be a collaborative approach,” she said.

“If she’s not identifying things in that conversation we’re guided by her and that’s the core principle of our practice.”

The worker disputed that a mandatory conversation about the risks of strangulation with a victim who discloses that behaviour and encouragement to report it to police could help.

“I don’t think police would necessarily actually act on that information and I question the intention behind what a mandatory questioning around strangulation and that conversation would be,” she said.

“I absolutely acknowledge and agree that’s a really important conversation to be had, I think there’s a time and place for that conversation to be had, but what’ the intention behind that, because police do a really good job when they can but there’s also a lot of barriers and a lot of systemic issues that police don’t respond the way they should.

“This isn’t a direct attack on QPS by any means but in my experience if we’re encouraging a woman to report something police and she does, if that even gets considered to be a criminal offence and goes down that pathway of being investigated, that can take weeks, sometimes months.

“And it’s not a pathway to safety, it’s a great mechanism for accountability if it works, but if we’re looking at imminent safety and risk, reporting that to police probably wouldn’t have changed the outcome.”

“It could have been really helpful at the time to have the conversation, I acknowledge that, but it’s not going to be a quick fix.”

Ms Hillard said in Hannah’s case there were potentially a number of charges police could have brought against Baxter including stalking, three separate instances of assault, sexual assault, rape and domestic violence order breaches.

“It’s quite a raft of potential charges to have been laid, that has a protective feature doesn’t it, for example if he goes to jail,” Ms Hillard asked.

The worker responded: “Yeah absolutely I don’t deny that but again looking at the time frame it happens in, it’s not a quick fix by any means and it also relies on the woman to provide her statement and go through that process and puts the onus on her rather than looking at him.”

The fourth witness from the Brisbane Domestic Violence Service said many women minimised the risks they were facing from their abuser.

She said women would often disclose more abuse to a support worker than they would to police.

“Many women are balancing the fear of police intervention as escalating the behaviour of their perpetrator,” she said.

She said having police share the criminal history of an abuser would be helpful.

The worker said a victim might not know how much risk they were facing because they were unaware of their perpetrator’s criminal history.

“I know it’s come up in discussion over the years,” she said.

“It would make life much easier.”

She said a comprehensive understanding of a protective order is of great assistance to workers in forming safety plans.

“We can only manage what we know,” the worker said.

She said information sharing between social workers and police from the Vulnerable Persons Unit had improved since the murders of Hannah and her children.

She said VPUs had been relatively new at the time.

“It takes time for women to tell their story … to tell of their fear, to look at their options … they disclose different things to different people,” the worker said.

The worker said reports of strangulation and petrol dousing had gone up by “50 per cent in some cases since Hannah’s death”.

“It’s become a much more active way of putting terror over to women,” she said.

“They just intimidate with it, there are others where they actually do it.

“There have been cases where other people have been injured from fire.”

Read related topics:Hannah Clarke