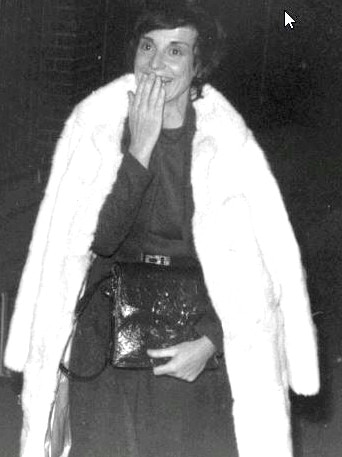

THE last thing Dorothy Edith Knight could have imagined, as a young woman from a respectable family growing up in Melbourne, was that fate would deliver her to the epicentre of one of the most important and historic moments in Queensland police history.

That she would unwittingly become entangled in the complex web of corruption in the Sunshine State, and that it would almost cost her her life.

Underbelly Brisbane: Whistleblower prostitute seeks compo

Police crack down on Brisbane’s lucrative private poker rooms

Fitzgerald inquiry: Reform which followed separated it from dozens of prior inquiries

But that was not on her mind when in the early 1960s she entered a mismatched marriage in her late teens. That, in turn, would see her flee her home town and go on the run throughout Australia, passing bad cheques and keeping ahead of authorities.

Until she arrived in Queensland, and was arrested for fraud in Townsville around 1967.

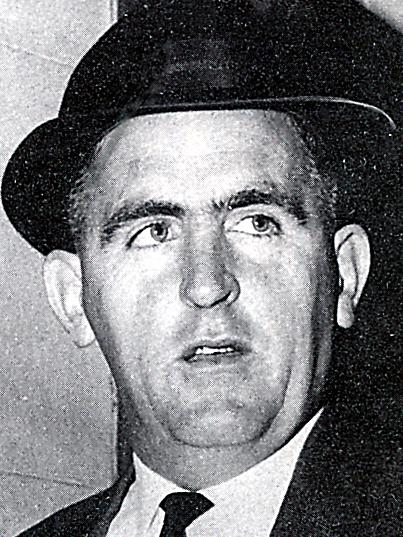

Out of nowhere, senior Brisbane detective Glen Hallahan arrived on the scene, and personally chaperoned the young felon down to Brisbane, where she would be convicted and briefly imprisoned.

But Hallahan, a member of the so-called Rat Pack of corrupt police officers, including Tony Murphy and Terry Lewis, got his hooks into Knight, and after she served jail sentences in both Queensland and Victoria, she headed back to the Sunshine State in the late 1960s and reacquainted with Hallahan.

For years he had been heavily involved in taking graft from prostitution, illegal gambling, and any scam he could earn a quid from, and before she knew it, Knight was working as prostitute under Hallahan’s close observation. He became her keeper.

“So I started working, right?” Knight, now 76, once said. “From the National (Hotel, at Petrie Bight), yes, from the National, and I used to get rooms at the National or go around to an old bird, I often wonder what happened to her, Mavis. Mavis with the green door.

“She had a boarding house up in Spring Hill. So all through this, Glen said to me – you’ve got to get you out of here, I’ve got a good friend who is running a good establishment – right?

“And then he suggested to me that, you know, that you’ve got to pay a certain amount of money to be able to work, and it wasn’t much in those days. But I guess a 20 or 30 dollars or whatever it was, it was a fair bit of money, wasn’t it?”

THE MADAM

Hallahan introduced Knight to Spring Hill brothel madam Lily Ryan, whose premises largely catered for the “racing crowd”. Not only was Hallahan getting kickbacks from both Ryan and Knight, but he used Knight as his “informant” on the comings and goings of the Spring Hill brothel.

During this time, Knight fell into another complex personal relationship. With Hallahan controlling her working life, and with an abusive partner who took the bulk of her earnings in her private life, Knight was beginning to fray. Something had to give.

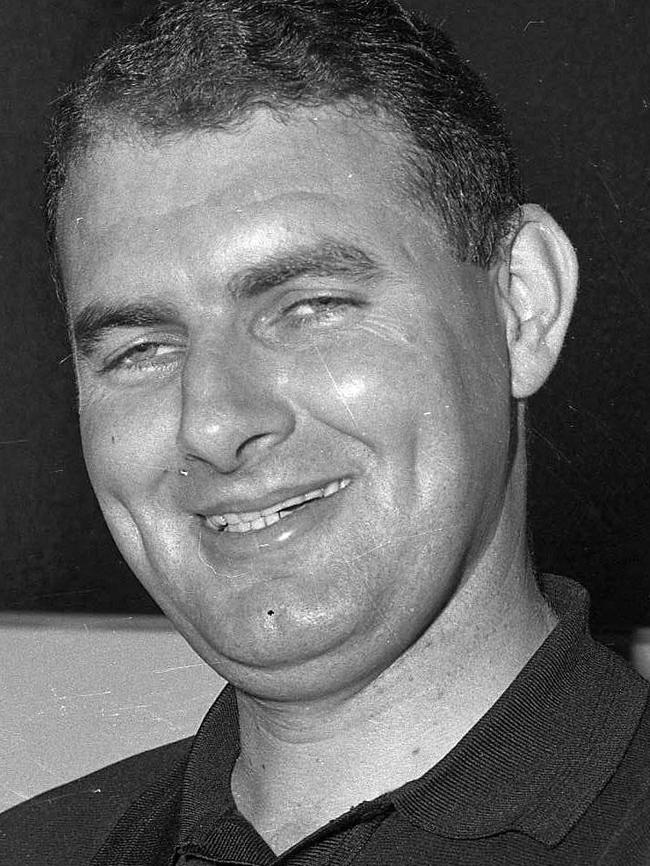

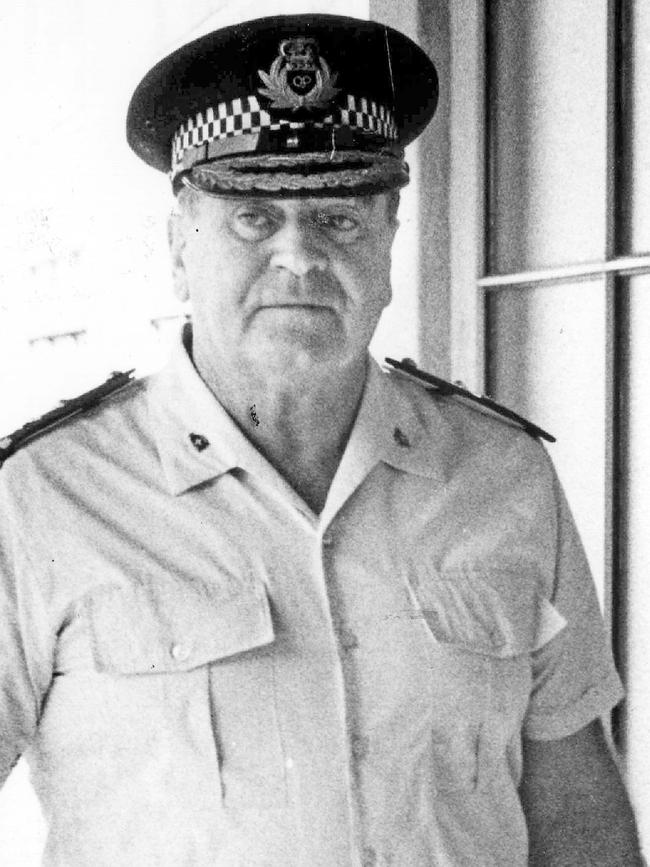

Then in the spring of 1971, she had two visitors to her rented property in Moray Street, New Farm. It was detectives Basil Hicks and Jim Voight from police commissioner Ray Whitrod’s crack anti-corruption squad, the Criminal Intelligence Unit (CIU).

The CIU wanted to nab Hallahan for official corruption, and they believed they had their best chance with Knight. If they could lure Hallahan into a carefully prepared trap, and get him to accept his extortion money from Knight in full view of CIU officers, they had a strong case.

Knight did not agree to help immediately, but she weighed up her options.

“I needed to get away from the life I was leading, and my relationship,” she says. “I saw this as a way out. I needed to get on with my life. This was my way out of everything. I was never meant to be there.”

So began almost ten weeks of training with Hicks and Voight.

UNDER COVER

Knight was put under immediate 24-hour police protection, and day in and day out she and the CIU officers would role play the moment that they would catch Hallahan.

For the first time in Queensland law enforcement history, Knight would be wearing a wire on the day of the sting. In the meantime, her phone was bugged and police were capturing valuable evidence against Hallahan.

“Suddenly I was tangled in the system,” Knight says. “They came in every other day and would train me up. Hicks was good at his job, but he was so insistent of getting Hallahan. One day he cracked when I told him I didn’t want to do any more talking on that day.

“We practised everything over and over. I couldn’t let anyone know what I was doing.”

Ultimately the big day arrived. Knight had agreed to meet Hallahan on a specific park bench in New Farm Park after 9am on Thursday, December 30, 1971.

CIU officers were inside a caravan parked on a nearby street, with cameras and binoculars trained on the park bench. Knight’s wiretap was linked to a receiving device in the van (the batteries would run out mid-operation). And undercover officers were spread throughout that section of the park. Some posed as gardeners.

A nervous Knight, 29, took her place on the bench and was joined by Detective Hallahan, 39, dapper as usual in civilian clothes, at about 9.23am.

“I was so bloody nervous,” Knight says today. “He looked at me and said, ‘Dorothy, I’m a bit worried about you, you don’t look well.’

“He insisted he drive me home because he believed I was sick.

“I gave him the money ($60 in cash – two 20s and two 10s).”

“Are you perfectly sure?” Hallahan asked about giving her a lift.

THE STING

She declined, and as Hallahan walked away, he was pounced on by arresting officers and taken to the city watchhouse for processing. Hallahan was charged with official corruption.

As for Knight, everything had been a blur, and she momentarily passed out.

“I was heading towards the caravan,” she says. “I fainted. I fainted for a couple of seconds. Someone held me up.

“Hallahan never had a clue. I often wondered what he might have thought after he was arrested. How could I get done by somebody like that? He must have thought – you’re joking, how could I have been brought down by such a very ordinary person?”

Police took Knight home, a doctor was called and she was sedated.

She could never return to work with Lily Ryan at Spring Hill, having given up Hallahan. But she had stayed in touch with some of her old clients, and began working one-off to survive.

Indeed, during the subsequent 14-months that she remained under constant police protection, she continued to work the streets. Often the officer on duty to protect her would drive her to her jobs and take her home afterwards.

In the months that followed the sting, she was physically attacked in Brisbane’s Albion Hotel for being the woman who ratted out Hallahan. One evening the barrel of a shotgun emerged through her open bedroom window.

DEATH THREAT

Then the protection stopped. Dorothy Edith Knight was left to fend for herself. Criminals associated with Hallahan would tell police years later that there had in fact been a “contract” put out on Knight, and that her assassin was to come from Melbourne. (Knight herself never believed the story of the death threat.)

“How did Hallahan manage to twist me around his little finger for all those years?” she still wonders. “I was used up like a dirty rag.”

Knight described herself as ordinary, when in fact she was the complete opposite. She had – unknowingly or not – managed to snare one of Queensland’s most notoriously corrupt detectives, and temporarily diminish the power of the Rat Pack.

The charges against Hallahan would miraculously fail in court, and he was wrapped over the knuckles for police administrative errors. On the back of the controversy, however, he resigned from the force. Hallahan would continue his corrupt activities virtually up until his death from cancer in 1991.

As for Knight, she did get “out of the game” shortly after the great New Farm sting, found a loving partner, and went on to raise a family and lead a thoroughly respectable life.

“My husband was a square head, he knew nothing about me,” Knight says. “He saved me. I don’t believe I’d be alive today if it wasn’t for him.”

It continues to amaze her how she stumbled into and got temporarily trapped in the corruption web of the late 1960s and early 1970s. It also surprises her that, unlike so any others who dared challenge the rife police corruption of the day, she survived to tell the tale. Women like Margaret Ward, Shirley Brifman and Simone Vogel, among others, were not so lucky.

LEGACY OF PAIN

Still, the ramifications of that historic day in 1971 continue to haunt her. She remains mentally and physically scarred by the event, and on occasion, as she’s going about her normal business, a face from the past will emerge from the crowd.

Suddenly, she’ll be back in her “other” life.

She still suffers anxiety, and that moment on the park bench in New Farm Park is never far from her mind.

“The reasons I didn’t do anything about this earlier was because I had two children,” Knight says. “I was worried about other people. I always thought in the back of my mind that somebody would approach me one day (about recompense). But they never did.

“I was absolutely used by police. It changed my life. They were obsessed with catching Hallahan. They were prepared to use any means to get him, and that included using me.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

The lie that cost underworld figure his life

When Carl Williams lied about Michael Marshall’s involvement in a contract killing, he as good as signed the hotdog salesman’s death warrant.

Lunchtime jewel heist which rocked Sydney’s CBD

In what was considered the biggest jewellery heist of the first half of the 20th century, in 1947 a thief managed to steal jewels worth about $600k today. But his glory was short-lived.