How a conman duped Australians with 26 aliases

From a bogus doctor to counterfeit clergyman to US consul-general, Australian con artist Anthony Duerdin adopted at least 26 fake identities. But it was more about chasing thrills than the cash. LISTEN TO THE PODCAST.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Anthony Duerdin was a conman whose approach to the game verged on being pathological. During his career he assumed at least 26 identities, all of them larger than life. For him it was more about the thrill of the endeavour than the fortunes to be made.

Duerdin is the subject of the final episode of our five-part miniseries on old Melbourne’s craftiest conmen in the free In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters.

“If people see no reason for suspicion, they will believe anything.” (Anthony Duerdin 1956)

Duerdin’s specialty was valueless cheques. His modus operandi was to arrive in town, big-note himself, spend freely with fake cheques, and then clear out before the alarm began to sound.

Born in England around 1900, Duerdin arrived in Australia in the early 1920s.

He quickly found employment teaching at an Anglican school in Melbourne.

Things went smoothly for him right up until 1926, the year he started his career as a conman.

1926 was also the year he met his first wife, Elsie.

Their paths crossed at a Melbourne religious conference and he impressed her by posing as a home missionary with aspirations to spread the gospel in China.

They were soon engaged to be married, but as the wedding date approached, Duerdin suggested a change of plan.

Instead of getting married in Geelong, he wanted a former religious colleague to perform the ceremony in Sydney. She agreed, and off to Sydney they went.

Unbeknown to Elsie, Duerdin’s former colleague was not a qualified celebrant at all. The marriage ceremony was nothing but a cruel fraud.

Later that year, Duerdin enacted his first money-making fraud.

He had some pages printed up with “Protestant Truth Society” letterhead and used them to order expensive items from multiple businesses via the post. Accounts were to be paid in due course.

Duerdin signed for receipt of the items at the post office, and then went and pawned them. It worked, but when he tried the same thing a year later, he got busted.

It was his first conviction and Duerdin talked his way into a good behaviour bond.

The conviction caused Elsie to do some investigating and she discovered their marriage was a fraud. On top of this she was pregnant. Duerdin cleared out and went to Queensland.

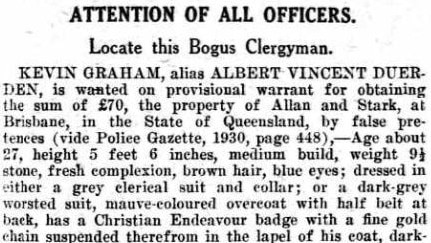

In Brisbane, he posed as an ordained minister from England.

He preached at various churches but left town because of “theological differences”.

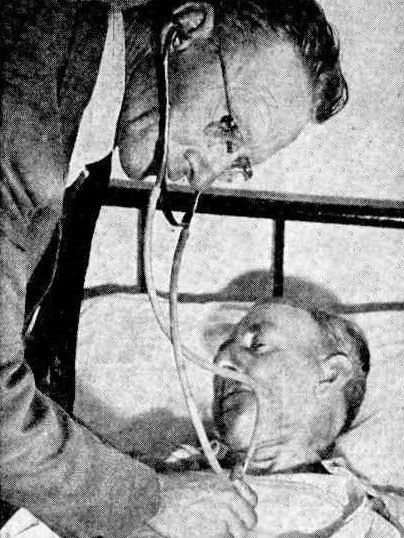

He then began practising as a doctor in Byron Bay, specialising in home visits.

He forged prescriptions for his patients and took them to the chemist himself. He was caught and received 3 months in Grafton Gaol.

After prison he got employment in Grafton as a layman with the Anglican Church.

He then contacted Elsie, professed his undying love, and proposed to get married again, properly this time.

They were lawfully married in Grafton in 1928.

Things seemed to be going well until, one Sunday morning, he put on his clerical garb, trotted off to church as per usual, and didn’t come back.

Elsie eventually returned to her mother’s in Melbourne.

Duerdin was next jailed in Queensland for cheque fraud. On release he preached at a Brisbane church, passed fake cheques on members of the congregation, ripped off the Reverend, and boarded a plane to Sydney.

In Sydney he bought a car with a fraudulent cheque and drove to Nelligen, south coast NSW.

In Nelligen he represented himself as a scientist with the Queensland Missionary Society and induced members of a local church to cash fraudulent cheques.

He then shouted a group of them to an all-expenses-paid trip to Canberra.

On arrival he took them to a grand hotel. He ordered an expensive banquet and instructed them to indulge, as money was not an issue.

When the party was in full swing, he asked to be briefly excused, and disappeared for good, leaving behind the bill and a lot of red faces.

From there he went to Melbourne and embarked on a shopping spree with fake cheques. He was using a forged letter from the Bishop of Grafton as part of his ruse.

Before long he was doing two years at Pentridge. There he wrote a letter to Elsie.

It was the first she’d heard from him since being abandoned in Grafton four years previously.

Again, he professed his undying love, but all he got back this time was notification of divorce proceedings.

Duerdin’s escapades didn’t get any less interesting after that.

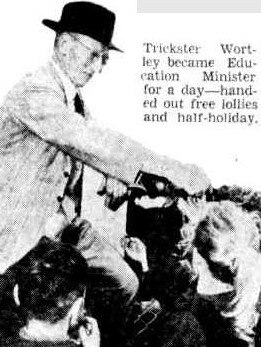

His assumed personalities included WWII Army General, Canadian Psychiatrist, American Vice-Consul, and Professor of Gynaecology.

He guest-lectured at Sydney University and was given tours of Australia’s major hospitals.

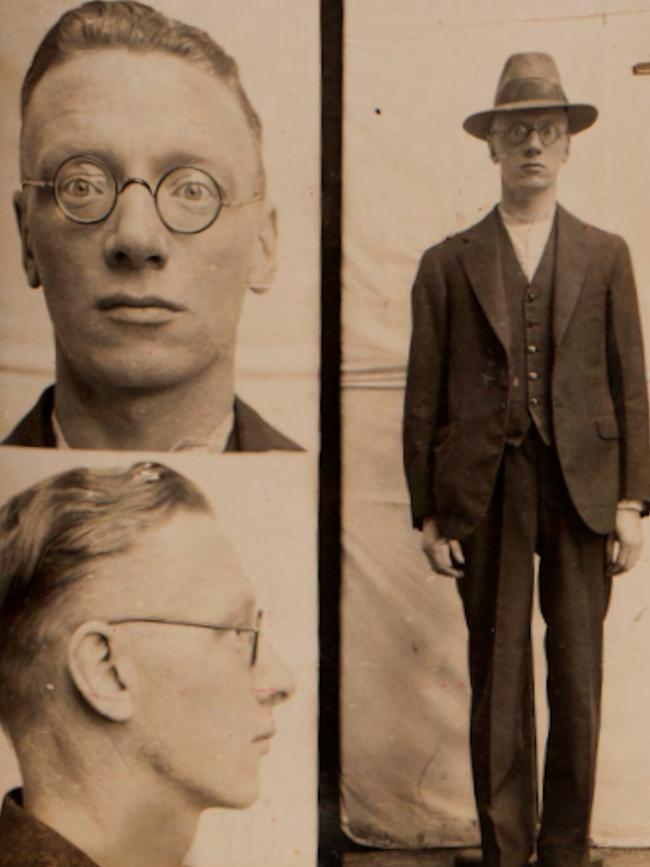

In the 1950s, Duerdin gave a series of ‘tell-all’ newspaper interviews from his cell in Pentridge. By then he’d spent twenty-five of his last twenty-nine years in prison and was known to police under at least 26 aliases.

His time on the outside had been spent exploiting others by posing as the type of person they trusted most.

He showed little remorse, saying that his victims had been made gullible by their own greed.

His major flaw as a conman was that he couldn’t resist pushing the envelope that little bit too far.

Though he was self-obsessed, and seemingly without conscience, his life was still superbly entertaining.

Michael Shelford is a Melbourne writer, researcher, and creator and guide for Melbourne Historical Crime Tours.

Listen to the interview with Michael Shelford now in today’s new free episode of the In Black and White podcast on Australia’s forgotten characters on Apple/iTunes, Spotify, web or your favourite platform.

And check out earlier stories in our series on old Melbourne conmen: how Paddy the Pig conned racegoers with a monkey and a barrel of marbles, how shonky undertaker Rev Charles Jones registered his own church to save on funeral costs, Smith Brown, the 1840s ex-convict who swindled Melburnians with one simple trick, and “Flash Jack” Donovan, the crooked showman who made a fortune from Ned Kelly’s hanging.

And see In Black & White in the Herald Sun newspaper Monday to Friday for more stories and photos from Victoria’s past.

inblackandwhite@heraldsun.com.au

Originally published as How a conman duped Australians with 26 aliases