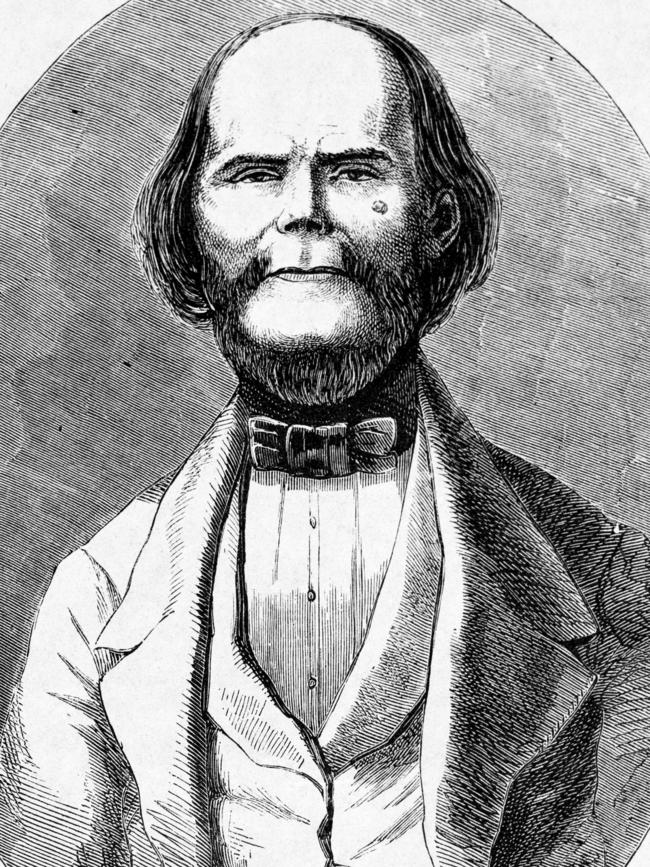

Escaped convict William Buckley: The man who gave us Buckley’s chance

His escape from the penal colony, which saw one convict shot and others turn back in despair, was itself against the odds. His survival for 30 years in the bush before re-emerging as the “Wild White Man”, defied them completely.

Our Criminal History

Don't miss out on the headlines from Our Criminal History. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When colonists led by John Batman arrived in Port Phillip Bay in 1835 to build a settlement, they expected some interaction with indigenous Australians. But they didn’t expect a tall, ragged white man, dressed and armed like a native, to wander out of the bush.

He was William Buckley, an Englishman who, after struggling to remember his native tongue, told of more than 30 years of survival in the bush. At first he lied that he was a shipwrecked sailor but eventually he revealed that he was an escaped convict who fled from a penal group in 1803.

DISCOVER: More of our criminal history at True Crime Australia

Buckley was born in Cheshire in 1780, the son of a farmer. Apprenticed to a bricklayer as a boy, he later ran away to join the army. He served in The Netherlands during the Napoleonic Wars and in 1802 he was arrested for knowingly receiving a bolt of stolen cloth, possibly part of a racket being run by fellow soldiers.

Tried by military authorities, he was at first set to labouring on building fortifications for the army before being selected for a new penal settlement under Lieutenant Colonel David Collins. He sailed aboard the Calcutta to reach the eastern part of Port Phillip Bay, later known as Point Lonsdale in what is now Victoria, in 1803. It looked like paradise but the soil was sandy and hard to cultivate and water was scarce. Within months Collins had decided to abandon the settlement.

Hope and despair: The hidden meanings behind convict tattoos

Waterloo: Aussie convict link to key moment in world history

Many prisoners tried to escape but were severely punished before Buckley himself decided to try to abscond. There was only slim hope of surviving the planned journey to Sydney but Buckley and five other convicts stole provisions and equipment and, thinking the guards would be busy celebrating, ran away on Christmas Eve 1803.

The guards were alerted, shooting one prisoner, letting only five get away. Two soon turned back but the remaining three trekked around the bay until they were opposite the penal settlement.

A boat approached but turned away, perhaps because the occupants thought the convicts were Aborigines. Buckley’s two companions lost heart and decided to turn back; they were never seen again.

Buckley decided to continue the journey, sustaining himself on berries and shellfish, while wandering along the seashore. One day he could feel his energy waning and plucked a spear out of a native grave mound to use as a crutch.

Some local Wathaurung people found him and seeing his white skin, believed he was a relative back from the dead.

The convict intently observed the ways of his adopted family. He soon learned the language and customs enough to fit in.

He was disturbed by the occasional violence, usually because of disputes over women or sometimes revenge attacks by rival clans blaming others for unexplained deaths of family members.

But other aspects of his new life were not questioned. Buckley came from a culture that still believed in fairies and other supernatural beings, so it was not hard for him to believe in bunyips. He heard of the creature from the Aborigines and he made no distinction between reality and myth.

Over the years he saw many whites in Port Phillip Bay but resisted making contact for fear of capture.

When Batman and his colonists arrived in 1835, Buckley overcame his reluctance and made contact, because he feared violence between natives and white invaders. It took time to remember how to speak English but he found his tongue. Batman took him on as an interpreter but he felt that both sides distrusted him.

Buckley resisted capitalising on his story and later moved to Tasmania, where he worked in various jobs. When he was talked into telling of his life, it never made him rich.

It did earn him a pension and some fame. He is now remembered in the expression “Buckley’s chance”, referring to his slim chance of survival. When a store named Buckley and Nunn opened in Victoria in 1851, the joke was “you have two chances: Buckley’s and none”. Buckley married the widow Julie Eager in 1840; they had a daughter. He died in 1856.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook

• This is an edited version of a story first published in April 2010

Originally published as Escaped convict William Buckley: The man who gave us Buckley’s chance