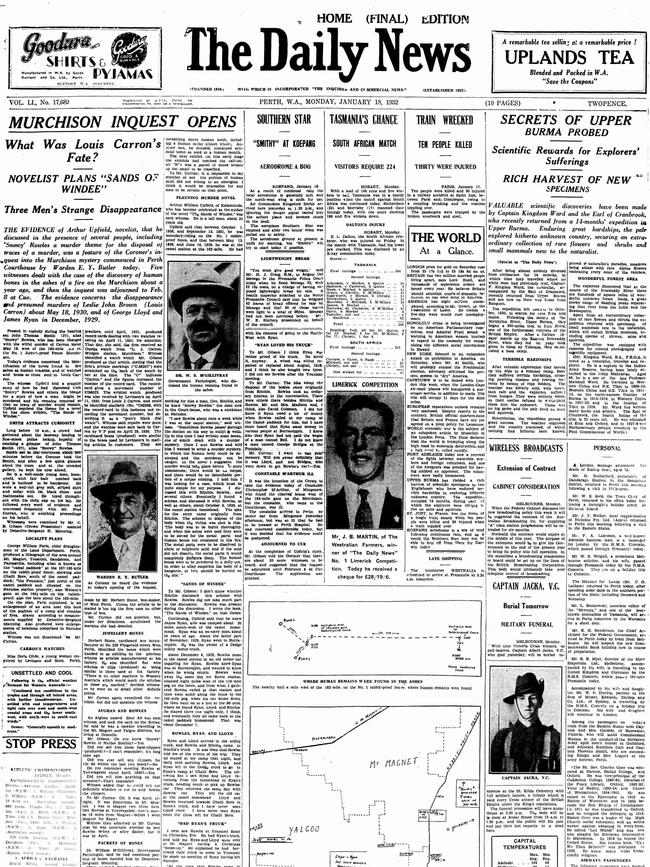

Writer’s quest for perfect murder inspired three outback killings

CELEBRATED mystery writer Arthur Upfield was looking for the recipe for a perfect murder. Little did he know a mate would try it and hang for his heinous crimes.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

BY the light of a fireplace at a remote outback camel breeding station, four men hatched a plot for the perfect murder.

For mystery author and part-time roustabout Arthur Upfield and two of his mates, this was a theoretical discussion that would form the basis of Upfield’s next novel.

But for one man that night, the fiendishly clever scheme was an inspiration that led to three murders and, partly on evidence from Upfield, would see him hang.

AUSTRALIA’S OWN DOG DAY AFTERNOON

HOW AUSTRALIA’S MOST FAMOUS FUGITIVES WERE CAUGHT

Upfield famously roamed the outback, picking up whatever work he could as he sought material for his stories, soaked in the isolation of Australia’s vast interior and learned about indigenous culture.

This was the source of his Bony crime series that centred on fictional Queensland Police Detective Inspector Napoleon “Bony” Bonaparte, a man of white and indigenous ancestry who had never failed to solve a murder.

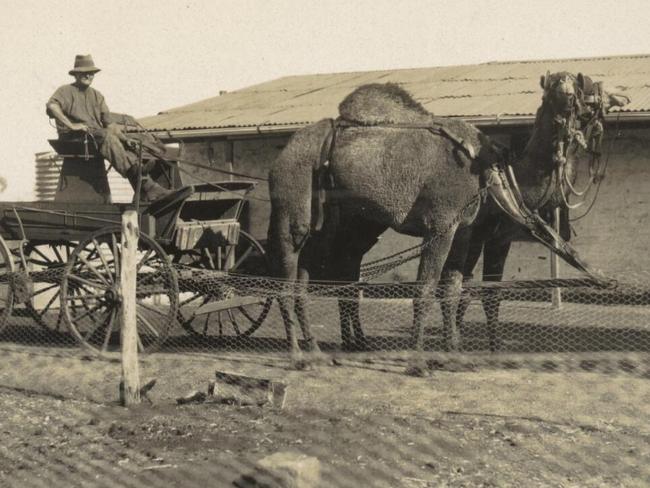

In 1929, he was a boundary rider on Western Australia’s rabbit-proof fence in the Murchison region of WA, a parched semi-arid inland area in the state’s central west.

The fence cuts across WA from Broome to the Great Australian Bight, and Upfield patrolled a 270km stretch of it with a camel-drawn tray, making repairs.

It gave a man like Upfield plenty of time to think, and to formulate the plots of his stories.

He had published his first Bony novel, The Barrakee Mystery, that year and was planning his second, The Sands of Windee.

He wanted to give Bony the case of his life in his new book — to solve a murder without the victim’s body, forcing him to prove that a murder was committed, how it was done and who did the deed.

When Upfield got together with workmates, they kicked around different plot ideas.

George Ritchie, the man in charge of the government Camel Station along the fence, gave Upfield the plot for an unsolvable murder.

He proposed to lure the victim into a scrubby area with plenty of dry wood, shoot him and burn the body right there. Later, he’d sift through the cooled ashes to remove all traces of evidence.

Any metal objects would be placed in sulphuric acid, commonly used for tin-smithing on rural properties, to dissolve them.

Any bones would be crushed to powder in a gold prospector’s dolly pot, freely available in the area, to be scattered in the wind.

He’d then burn the carcasses of a couple of kangaroos to muddy any scientific evidence that a human body was burned there.

Fire was a common way to dispose of animal carcasses to keep the flies down.

Upfield, Ritchie and many others including local station hand “Snowy” Rowles, kicked around the idea for weeks, looking for any flaws. None did.

On October 5, 1929, Upfield, Ritchie, Bowles and another boundary rider met again and dissected the plot. Upfield noted the presence of Rowles and the others in his diary — a point that would become critical later.

Rowles left his employ at a local station a few weeks later but remained in the area with work poisoning foxes.

Upfield let Rowles stay with him on occasion in the hut where he stayed on the fence, describing Rowles as an excellent guest — good company who did his share of the chores and kicked in his share for rations.

Around November 24, another man, a contractor called James Ryan arrived at Upfield’s hut on his way to the town of Barracoppin, driving a Dodge car.

About a week later, on the night of December 1, Ryan returned to Upfield’s hut, having rescued Rowles’ broken-down car in the company of another man, George Lloyd. The three stayed the night, with Rowles planning to join Ryan on a trip to WA’s northwest.

Soon after, Ryan and Lloyd disappeared.

On Christmas Eve, Upfield ran into Rowles unexpectedly at nearby Youanmi while buying supplies. Rowles was driving Ryan’s Dodge, which he told Upfield Ryan had loaned him. Ryan, he said, stayed at Mount Magnet. But he told a mutual friend the same day that he had bought the truck from Ryan for 80 pounds.

No one, including Upfield, was suspicious. Itinerant workers coming and going was nothing new, and it was possible that Ryan loaned or sold his car to Rowles.

Upfield later learned that a hand from a nearby station, Louis Carron, had resigned and left in the company of Rowles in April 1930.

Rowles, still driving Ryan’s Dodge, had cashed Carron’s last pay cheque at Paynesville, a mining town, and bought beer.

Carron’s disappearance may never have been noticed if not for Jack Lemon, a man who’d arrived in the district with Carron from Perth.

The men worked on neighbouring stations and stayed in touch by mail.

Lemon sent a reply-paid telegraph to Rowles seeking information on Carron’s whereabouts — a telegraph Rowles received but never answered.

Carron, a New Zealander, wrote letters regularly to friends at home and to Lemon.

Detectives began investigating in January 1931 when Lemon alerted police.

They were well aware of Upfield’s search for the perfect murder and Rowles’ role in its formulation.

The search began for Carron. Rowles, now working on a station a couple of hundred miles north of Youanmi, was the prime suspect because Carron was last seen alive in Rowles’ company.

As police investigated, it became clear that Lloyd and Ryan were also missing, and were also last seen with Rowles.

Carron’s charred remains were found a short distance from the 183-mile hut along the rabbit-proof fence in February 1931.

In the ashes remained items including human and animal bones and bone fragments, some teeth, gold clips from a dental plate, gold clips from a dental plate, one molten lead piece of a weight equivalent to a .32-calibre bullet and, most significantly, a wedding ring.

When police went to arrest Rowles, the lead detective in the case, Detective Sergeant Harry Manning, recognised him as John Thomas Smith, a man who had been convicted of burglary but escaped from the lockup at Dalwallinu in 1928.

Smith was charged with the murder of Carron, but not with those of Ryan and Lloyd.

Scars from other fires were discovered near the fence at Challi Bore, and items including boots and an accordion like one that had belonged to Lloyd were also discovered, but there were no signs human body parts had been burned there.

It was generally assumed Smith had murdered both men and destroyed their bodies there, following Ritchie’s murder instructions to the letter.

But it appeared he had been less careful in disposing of Carron’s remains, failing to crush some bones or destroy key metallic items in sulphuric acid.

The Sands of Windeewas published following Smith’s arrest in 1931.

Smith was held at Fremantle Gaol until his trial in early 1932.

He pleaded not guilty, insisting that the murder had never taken place.

Carron’s wife and an Auckland jeweller both testified that the wedding ring was Carron’s.

The ring was re-cut at the jeweller shop, but a young assistant accidentally rejoined the ring with a 9-carat gold solder, leaving a distinctive mark in the otherwise 18-carat gold ring.

Upfield detailed the night in October 1929 that he, Ritchie, the man now identified as Smith and another boundary rider discussed the murder plot, and gave evidence about earlier discussions involving Smith.

Bizarrely, as Perth newspapers reported every detail of the trial, one paper also published a serialised version of The Sands of Windee.

After six days of evidence, on March 20, 1932 it took just two hours for the jury to find Smith guilty of Carron’s murder.

Smith shook his head as the verdict was read, and denied his involvement in the crime until the end. “I have never been guilty of a crime that has never been committed,” he told the court before he was sentenced to death.

Smith was hanged on June 13, 1932, aged 26.

The publicity of the case brought Upfield world fame and helped him to become one of Australia’s most successful authors.

YOU CAN READ UPFIELD’S OWN ACCOUNT OF THE CASE AT THE STATE LIBRARY OF VICTORIA WEBSITE

Originally published as Writer’s quest for perfect murder inspired three outback killings