First the police came, to the school in the little seaside town where everyone knew your name.

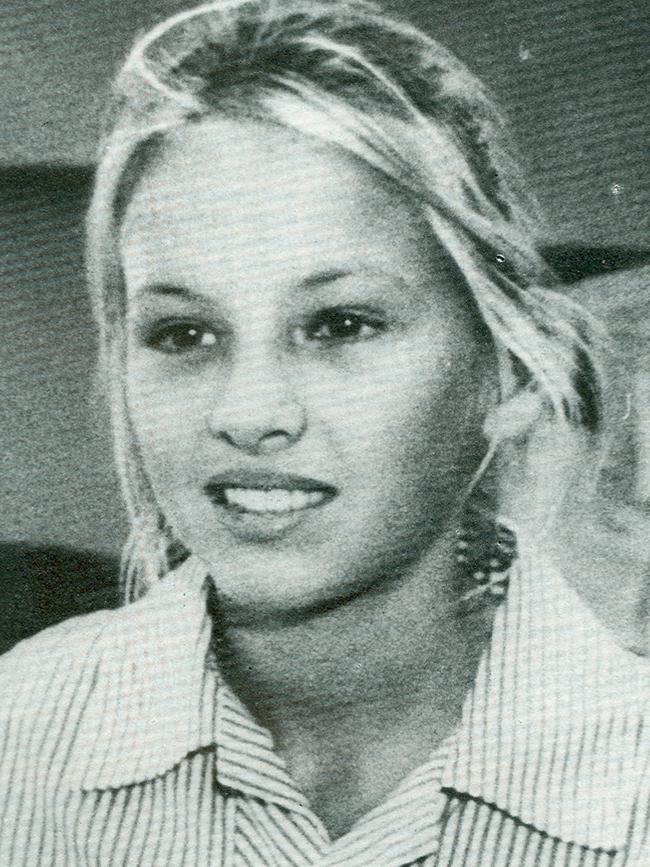

She’s been found, they said: a body in the bush. Sian Kingi’s seventh-grade teacher broke down. She cried, sobbed, gasped for air. And then she pulled herself together. Tried to convince herself there was some way to tell those children their friend had been murdered. Twelve-year-old Sian, shy and beautiful and friends with everyone. Abducted, raped, stabbed and dumped in the bush.

The Noosa of the 1980s bore no resemblance to the place it is today. Back then it was a small country town – a place where kids rode their bikes from school to the beach for a swim before dawdling home. It was a safe place; dirt roads and beautiful bushland.

“My strongest memory of Sian is her constant smile,” close friend Nathan Bath said.

“She was such a happy girl ... such a striking girl. She would have been the most beautiful looking woman, just stunning. She had a beautiful nature. You never saw her without a smile.”

Nobody in Sian’s close-knit group of friends from Sunshine Beach State School has forgotten a single moment of the day she disappeared.

It was November 27, 1987, and the end of the school year was approaching.

Emma Forsyth remembers playing basketball in the school’s undercover area that Friday afternoon. Her mum was a teacher at the school back then – Jenny Forsyth had taught Sian in sixth grade.

Emma remembers spotting Sian helping her teacher, Chrissy Pobar, carry books to the car.

“She stopped and asked me what I wanted for my birthday,” Emma said.

Emma’s 13th birthday party was just days away. They were having it in the national park. The whole class was invited and Sian had been looking forward to going.

Soon after, Jenny and Emma Forsyth left school, stopping at the supermarket on the way home. They ran into Sian and her mother Lynda there. They would be among the last to see her alive.

Sian rode her bike home from the shops while Lynda drove, the schoolgirl taking her usual route home via Pinaroo Park. It was a short ride, but when Lynda arrived home, Sian wasn’t there.

Lynda thought perhaps her daughter had run into friends, but as more time passed, her worry grew. She started calling the parents of Sian’s schoolmates. She and husband Barry retraced Sian’s steps and horribly discovered their daughter’s abandoned 10-speed at the park. They drove to the police station.

Emma was supposed to have met Sian at the movies on Friday night but she hadn’t shown up. There’d been a group of them meeting for popcorn and a movie in their safe seaside town.

When Sian didn’t arrive, they hadn’t been too worried. It was long before mobile phones. Perhaps she’d changed her mind.

“Mum and dad must have been going out for dinner because I was staying at my grandparents’ that night,” Emma said.

“Mum woke me up at 11pm and said `did Sian go to the movies with you?’ and I’d said `no, she didn’t’.”

The next day, Saturday, Jenny Forsyth was driving her daughter to another girl’s birthday party. She’d pulled in at the shops and asked Emma to get some milk.

“Mum had told me they were looking for Sian but the penny hadn’t dropped that something really bad was happening,” she said.

“She asked me to run in and grab milk for her and I remember walking past the piles of newspapers and seeing a massive full-page photo of her in her school uniform.

“I got back in the car and burst into tears.”

Emma’s birthday party was on the Sunday. Police hadn’t wanted it held in the national park. They thought they might have a killer on the loose.

“All the girls came to our place,” Jenny said.

“The boys from the class got on their bikes and patrolled the park looking for her at the same time the party was on – just in case she turned up.”

Chrissy Pobar still teaches at Sunshine Beach State School – more than 30 years later. It’s her connection to Sian.

“That week she was missing, it was just horrific. It was awful,” she said.

“The kids got themselves into vigilante groups and were searching for her.

“We had to say to them, please stop going to the beach, please stop going to parks looking for her.”

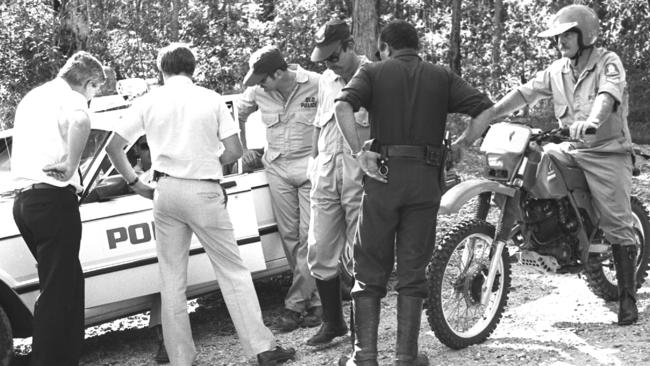

Behind the scenes, police were pulling out all the stops. The detective sergeant on duty at Noosa police station the night Sian went missing was Bob Atkinson. Det Sgt Atkinson – who would go on to become the Commissioner – managed to get Sian’s photo in the next day’s paper, despite the late hour.

Media coverage brought about important leads from the public. There’d been sightings of a white Holden Kingswood station wagon at the park where Sian vanished. A surfer had seen it at the beach earlier that afternoon – its driver had left him so unsettled he’d jotted down the registration.

That registration was linked to a series of attempted abductions of nurses from the Ipswich hospital days earlier.

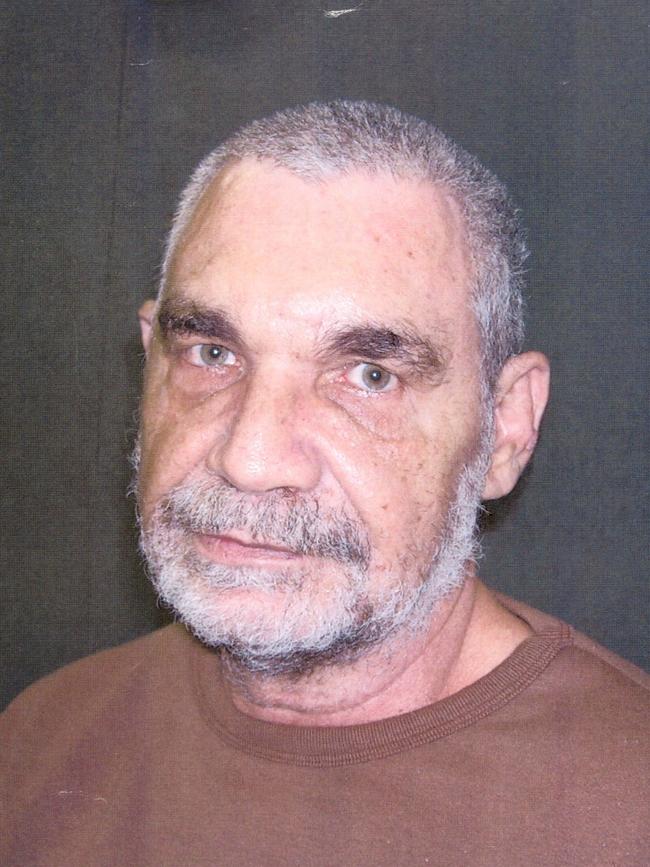

It would also lead police to Barrie Watts and Valmae Beck – a couple with a lengthy criminal history.

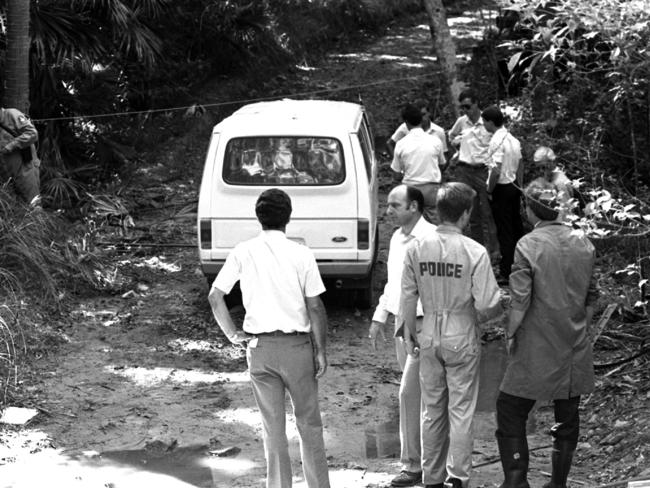

They found Sian on December 3. Her body had been discarded 15km away in the Tinbeerwah Mountain State Forest, still in her school uniform, her pink socks and white joggers still on her feet.

Watts, bored of the wife who was 10 years his senior, had recruited her to help him abduct a virgin girl for him to rape. She’d been bound, raped, strangled and stabbed. Her throat had been cut.

Police came to the school and a select group of staff were told the news. Ms Pobar still feels the trauma of that day. She remembers the anger, the sobbing. Trying to pull herself together. How do you explain something so evil to children so innocent?

“She was probably one of the shiest little people at that school,” she said.

“She was just beautiful – but didn’t think she was beautiful. She’d clutch at the top of her dress sort of thing. Very, very sweet.”

There’d been no text messaging in those days, no email. Staff had had to call every child’s parents and tell them to come and collect their son or daughter.

“Telling the kids was a nightmare,” she said.

“I had to pull it together and calm them down. The boys literally hit holes into the walls. They lost it. It was awful. It flowed on to kids who had never even met her. Teachers were crying.

“Little grade twos were hysterically crying and not even knowing why. It was all encompassing.”

Mr Bath said he will remember it until the day he dies.

“I could see mums milling on the grass outside by the demountable buildings,” he said.

“I remember looking out … and seeing this girl walk outside and collapse in tears.

“I remember a woman coming into the classroom and saying they’ve found Sian. There was a pause. And she said `she’s dead’.

“One girl started crying, then another, then in the space of a minute or two there’s 80 kids bawling their eyes out. There were kids wailing. We just couldn’t understand it.

“You didn’t know what rape was back then. You didn’t know what abduction was. To process and comprehend that a girl you went to school with was abducted and raped and stabbed. It didn’t make sense then and it doesn’t make sense now.

“It’s f--king insane that there are people out there who would do that.”

Sian’s friend Emma Anderson can’t forget that day either.

“I was the first one to respond. I stood up and ran out of the classroom. And I just ran,” she said.

She remembers a friend running after her to see if she was OK. That boy is still her friend today.

“I’ve never, ever forgotten him doing that,” she said.

There are other memories that have never left. In the days that Sian was missing, Ms Anderson’s mother took her to see the Kingis.

She walked in the front door and through to Sian’s bedroom.

“Sian’s best friend was sitting on her bed with her head down, holding one of Sian’s toys. I went and sat with her,” Ms Anderson said.

“That memory is scarred into my brain. I’ll never forget it.”

Things moved quickly after they found Sian. Watts and Beck were on the run but had made the mistake of sending a money order to cover their rent from The Entrance in New South Wales. Police found them there and brought them back to Noosa to face justice.

“They had him (Watts) at the cop shop,” Mr Bath said.

“I remember telling mum and dad at dinner I was going to go up to the cop shop the next day. Me and my mates were going to sort him out.

“My mum said absolutely not.”

The passage of time has healed no wounds. The friends who lost Sian saw the news that Watts had applied for parole and bawled like they had the day they’d been told she was dead.

They can’t believe their grief. They don’t know how her parents have survived it.

Mr Bath remembers seeing Lynda and Barry at the funeral – a beautiful open-air memorial filled with Maori tradition.

They’d hugged every single person who’d come, an act of generosity while police covertly filmed in case the killer turned up.

“I remember her mum and dad. Her dad standing there so staunch,” Mr Bath said.

“I remember the next day my dad tearing up and saying `strong as a bull that bloke – I don’t know how he did it’.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

‘I miss being able to talk to them’: Tribute for slain Aussie brothers

A tribute has been unveiled where Australian brothers Jake and Callum Robinson and their American friend were murdered during a surf trip.

Melb private schoolboy’s stunning Russian mafia admission

An investigation into former Melbourne private schoolboy Damien Carew has taken a dramatic turn after his latest police confession.