New recording of Kathleen Folbigg talking about her children

Kathleen Folbigg, the Australian woman convicted of killing her four children, opens up for the first time about her victims in a new tape.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Exclusive: The very diaries that helped convict child killer Kathleen Folbigg may now hold the key to overturning her convictions.

Four leading experts have come forward to contradict the long-held view that the diaries were a “virtual” admission of guilt to murdering her children Patrick, Sarah, Laura and for the manslaughter of her firstborn Caleb – who died between 1989 and 1999.

Folbigg – who is now in her 19th year behind bars – has always protested her innocence.

At her trial, Senior Crown Prosecutor Mark Tedeschi QC, argued her diaries were “the strongest evidence the jury could possibly have for Ms Folbigg having murdered her four children.”

More recently, former District Court Chief Judge Reginald Blanch, who headed an inquiry into Ms Folbigg’s convictions in 2019, said the evidence he had heard, including her own explanations of what the diary entries meant, “reinforces Ms Folbigg’s guilt”.

Now four leading experts who analysed Folbigg’s diaries have formally submitted their opinions to NSW Governor Margaret Beazley AC QC, and to NSW Attorney-General Mark Speakman, as part of a petition originally lodged in March – and which has now been backed by 150 eminent scientists, science advocates and medical experts from around the world – calling for Folbigg to be pardoned and released.

“I am comfortable in describing Ms Folbigg as having been a very loving and attentive mother …,” psychotherapist Dr Kamal Touma said.

“After reading and analysing the minute particulars of Ms Folbigg’s diaries and having met her for five analytical psychotherapy sessions, I cannot see anything in the diaries or from my sessions with Ms Folbigg to indicate that she harmed her children.”

Dr Touma, who had five audiovisual consultations with Folbigg, concludes that she is suffering from primary and secondary “dissociation” following traumas she endured in her childhood, including the death of her mother at the hands of her father, when she was 18 months old.

When it came to her own children dying, Dr Touma said: “the painful aloneness of being dissociated with and from her feelings is illustrated by this simple heartbreaking entry in her diary the day her daughter Sarah died: MONDAY 30: SARAH LEFT US.”

But Dr Touma rejects the notion that she may have killed her children in severe dissociative, fugue like states.

“Her dissociation is nowhere near the severity of a dissociative disorder that one would expect to observe with such phenomena,” he said.

“Nowhere in the diaries nor in my conversation with Ms Folbigg was this observable. I can comfortably exclude this hypothesis.”

When Dr Touma spoke to Folbigg, he was struck by how she spoke about her children.

“A written transcript cannot reflect what we may call the ‘musicality’ of the moment where immersed in associative thinking she talked about her children. This is the true memories she keeps of her children and wasn’t since losing them able to access to express. This is not how a murderous mother would ever talk about her children,” he said.

A second expert, US-based psychologist and textual analyst Professor James W. Pennebaker, who has helped the FBI and CIA understand the language of kidnappers, terrorists and violent criminals, said: “I see absolutely no evidence to suggest that these were premeditated murders.

“I see no evidence that Kathleen Folbigg’s language … exhibited any signs of deception or attempts to cover anything up. I also see no sign that Folbigg is mentally unstable or is someone harbouring buried hostility or rage,” Prof Pennebaker said.

A third expert, consultant psychiatrist Associate Professor Janine Stevenson, said: “Nowhere in her journals does she use agency verbs, such as ‘I hurt her’ … Throughout the journal Ms Folbigg is detailing all the steps she took to ensure the safety of her children. There is no anger, no aggression, only self-doubt.”

And a fourth expert, Associate Professor of Linguistics Professor David Butt, said: “There is a likelihood that the courts and Inquiry have misinterpreted the feelings of responsibility for not being a better mother as admissions of agency in the deaths of the children.”

Folbigg’s legal team has also resubmitted a report from Clinical Psychiatrist Dr Michael Diamond, who met Folbigg and assessed her before writing a report for the 2019 Inquiry, in which he said: “I found no evidence to support a view that Ms Folbigg has suffered from psychotic illness, severe mood disorder consistent with homicidal conduct or any other brain injury that might affect her conduct so as to carry out homicidal acts.”

Dr Diamond diagnosed Folbigg with complex post-traumatic stress disorder. Dissociation is frequently observed with those who suffer from c-PTSD.

A sixth expert report submitted from Clinical Psychologist Dr Sharmila Betts questioned how the diaries could be “tantamount to confessions” as asserted by the Crown.

“[That assertion] is misleading and unsupported by my reading of the diaries or the psychological literature on maternal adjustment, in both bereaved and non-bereaved mothers … In my opinion, the diaries do not contain any clear admission of guilt or confession of homicide,” Dr Betts said.

Instead, she writes: “Ms Folbigg’s entries suggest periods of depression but largely her beliefs consist of unremitting self-blame.”

Dr Betts’ report was originally submitted as part of an earlier petition on Ms Folbigg’s behalf in 2015 and has since been updated.

In 2019, the Inquiry’s Commissioner Blanch dismissed the suggestion that experts could help him understand Folbigg’s diaries.

“I would not be assisted at all in this Inquiry by a psychiatrist who wanted to come along and tell me a) what the words of the diary mean or b) about the fact that a mother who had lost her babies would be upset and emotional and so on,” he declared.

Instead, he said: “I am satisfied that the plain meaning interpretation of the diary entries carries the character contended by the Crown at the trial, of virtual admissions of guilt,” adding: “Even making every allowance for her deep-seated psychological subjective experiences and childhood trauma, and any emotional state she may have been in at the time of writing the various entries, it is impossible to give the diary entries any meaning other than their ordinary English meaning.”

But the experts offer a different insight into Folbigg’s mind through examining her diaries.

Associate Professor in Linguistics at Macquarie University David Butt said the 175 pages of Folbigg’s diaries – which he studied – “do not at all convince me that the claim of a single plain meaning is sound”, and contends that the diaries could be “cherry-picked” to focus only on “those wordings that permitted some possibility of an interpretation of guilt.”

“It is not reasonable to claim that the diaries of Kathleen Folbigg support only one ‘damning’ interpretation,” he said.

None of the fresh expert opinions support the view that the diaries reveal an intent on Folbigg’s part to harm or murder her children, or that they carry any admission that she did so.

“At first I did find some of her diary entries troubling, but when taken in the context of her mindset, that she basically hated herself and everything she did, they are a lot less troubling,” Assoc Prof Stevenson said.

“It is not possible for a therapist, let alone a lay person, to interpret the meaning of writings in a diary. They are personal, idiosyncratic, expressing fleeting feelings, imaginings, and very influenced by the emotions of the minute … The ‘meaning’ one day could be different the next, or there could be no meaning at all,” she said.

Based on Assoc Prof Stevenson’s opinion, Folbigg’s lawyers argue that “this makes the inculpatory interpretation of guilt by judges (and presumably the jurors at trial) highly likely to be wrong.”

In a direct challenge to Inquiry Commissioner Reginald Blanch, the lawyers argue the Commissioner should have sought expert opinion to assist him instead of “discounting Ms Folbigg’s explanations without the benefit of context”.

“It is clear that the courts and Inquiry have misinterpreted Ms Folbigg’s words. Nowhere in the diaries/journals are there confessions of murder and they should stop being used to suggest this,” they said.

Solicitor Rhanee Rego and barrister Robert Cavanagh, who prepared the petition, said this week: “Experts now say that the diaries cannot be taken as confessions of murder or harm to any of her children.

“The only consideration is reasonable doubt. Every argument that has been used to suggest the guilt of Ms Folbigg has now been overcome and her convictions are untenable. Now no

reasonable person can conclude that Ms Folbigg’s guilt is established beyond reasonable doubt,” they said.

“It’s time for Mark Speakman to recommend to the Governor that Kathleen Folbigg be released.”

In a statement, the Attorney-General said: “These materials are voluminous and complex. They will be subject to thorough consideration.

“It would be inappropriate to provide further comment at this stage.”

THE TAPE

Psychotherapist Dr Kamal conduced five audio-visual consultations with Kathleen Folbigg between June 25 and August 13 this year, each lasting about 45 minutes.

In one of her sessions, Folbigg opens up for the first time about her four children.

This is an edited transcript, published with Folbigg and her legal team’s permission.

“I don’t have trouble now talking about … if I can remember funny stories or a personality trait that was amusing or something like that. I’m fine sharing that sort of stuff now.

Each one of them was just a little bit different in each of their own way.

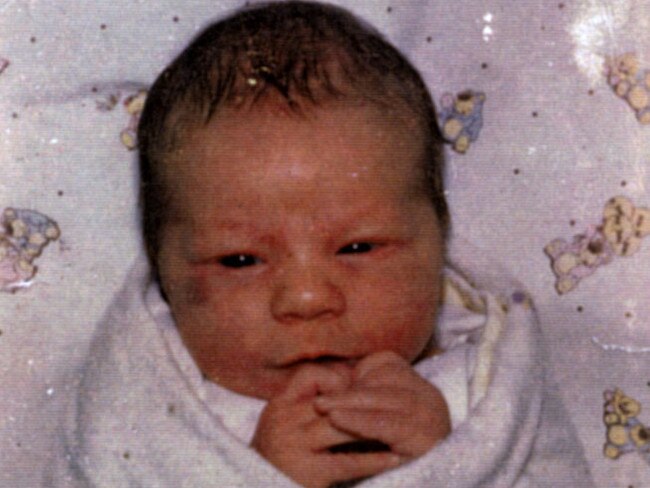

Caleb

“Caleb might have been only 19 days old, but he just came across as a little old soul. He was so serious when he stared at you. He had these such intense eyes it was just sort of like ‘ my gosh I think he’s reading my brain’ because he would just stare at you so intently and he was just placid and really calm. And you just sort of thought ‘wow’.

I remember he had such long fingers I just sort of thought ‘piano player’ – you instantly think of playing pianos or something because they’ve got these really long fingers and things.

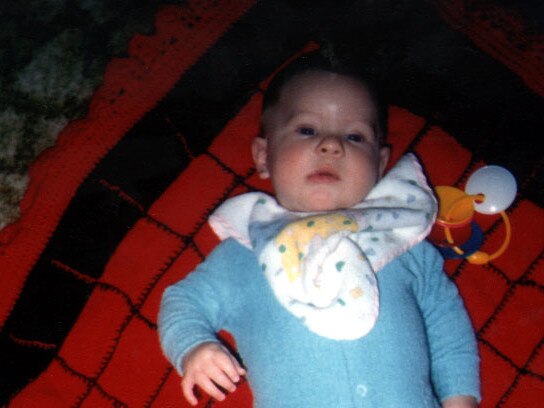

Patrick

“Even with all his medical issues and his all of his problems with epilepsy and his blindness, I sort of thought ‘he’s going to be a risk taker, I can just see it’ because he would just roll around the floor with no concept that he might be banging into things or going and getting himself stuck under something or just hurt himself in any fashion. He would just go for it. He would be rolling around the floor. I remember that I would quite often go into the living room and he would not be where I put him because he’s gone and rolled somewhere and gone some investigating of his own with his hands …

With him there was no stopping him from discovering things even though he couldn’t see. He was very tactile and hands-on.

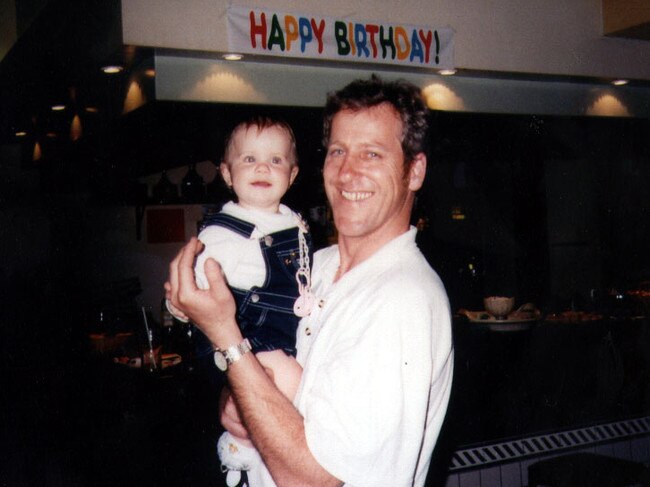

Sarah

“I actually thought Sarah was probably a bit too much like me. I saw her as … I anticipated she was going to be one hell of a handful because she was just cheeky. There was just cheek that would radiate from her. She was just … if you turned around and called her name – her instant response was to poke her tongue out at you. And she just took such funny joy – it didn’t matter what she was doing, there was fun. Having a bath was excitable, playing with toys was excitable, running around with dad was excitable. She was full on. We’d go to playgroup – as long as she could see me and she knew where I was, she would just take off and she would go and get into all sorts of stuff. I just sort of had visions of her being in the future as we were going to have to watch what she was up to.

Laura

“Laura was different again. She was very … I already was starting to see that she was quite an empathetic and compassionate little kid and she would quite happily share … wanting to help in some fashion. She was different again.

“They all had their own little things even at the ages that they were. But if you had tried to get me to share that sort of information with you in the first five – 10 years maybe, I probably would have gone ‘nope, you’re not having any of that – that’s mine. I’m keeping that, you don’t get to know any of that …’

I think it was just a subconscious thing, I would just go blank and just go ‘yeah, no, I’m not dealing with this. I’m not having these conversations … I’m not going there’.

I realise now that it came across as me being incredibly cold and not caring. But it was what I did. I did that to protect myself more than anything else.

Originally published as New recording of Kathleen Folbigg talking about her children