From landmarks for sale to Balloon Boy: 10 crazy cons

From celebrity imposters to serial fraudsters, here’s how the world’s most infamous con artists pulled off history’s biggest hoaxes.

Crime in Focus

Don't miss out on the headlines from Crime in Focus. Followed categories will be added to My News.

When infamous conman Hamish Earle McLaren was finally held to account for his life of lies last week, his victims applauded in court.

McLaren, from Sydney, will serve up to 16 years after swindling more than $7.6 million from victims including his girlfriends and mates, with the NSW District Court judge saying: “I do not believe he has any remorse.”

The case gained international attention, with McLaren’s exploits detailed in The Australian’s popular podcast Who the Hell is Hamish?.

But his actions were far from unique — the Ponzi scheme he used is one of the oldest cons in the book.

Over the years, we’ve seen slick salesmen selling off the world’s most recognised monuments, brazen celebrity impostors and a hair-raising hoax (or was it?) supposedly fuelled by the desire for a TV show.

Here are some of the world’s most infamous cons:

THE SALESMEN

American Victor Lustig was an incorrigible conman, but it was his gutsy scheme to sell the Eiffel Tower for which he is best remembered. Travelling to Paris in 1925, he posed as a French government official and persuaded his marks that the tower was being sold for scrap because it had fallen into disrepair. He then zeroed in on one of the scrap metal dealers, suggesting a bribe would secure the contact. The dealer paid up and was too embarrassed to tell the authorities when Lustig disappeared and it was clear he’d been duped. Buoyed by his success, Lustig went on to pull the exact same scam a second time, but this time the police were on his trail and he had to flee to the US.

Mithilesh Kumar Shrivastava, better known as Natwarlal, was India’s king of the con, repeatedly “selling” the country’s famous landmarks — the Taj Mahal, the Red Fort and the President’s residence, Rashtrapati Bhavan — to gullible tourists, among many other scams. The few times he faced justice, he escaped jail and, according to one story, he even scammed money in court. India Today reports a judge hearing his case asked him: “How do you do it.” Instead of replying Natwarlal asked the judge for a rupee. The judge took out a currency note from his pocket and handed it over to the master cheat. Natwarlal pocketed the money quietly and told the baffled judge: “This is how I do it.”

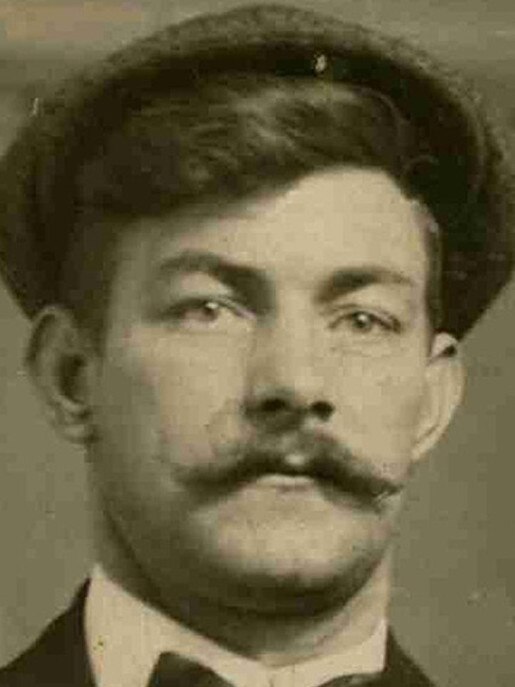

In America, it was the Brooklyn Bridge up for sale as New York-born hustler George C. Parker plied his trade. According to legend, the 20th century con artist was able to unload the landmark twice a week for many years, with police often having to stop the new “owners” installing toll booths. But his luck ran out in 1928, over a far more mundane fraud — cashing a worthless cheque — when he was jailed for life under mandatory sentencing rules.

THE IMPOSTORS

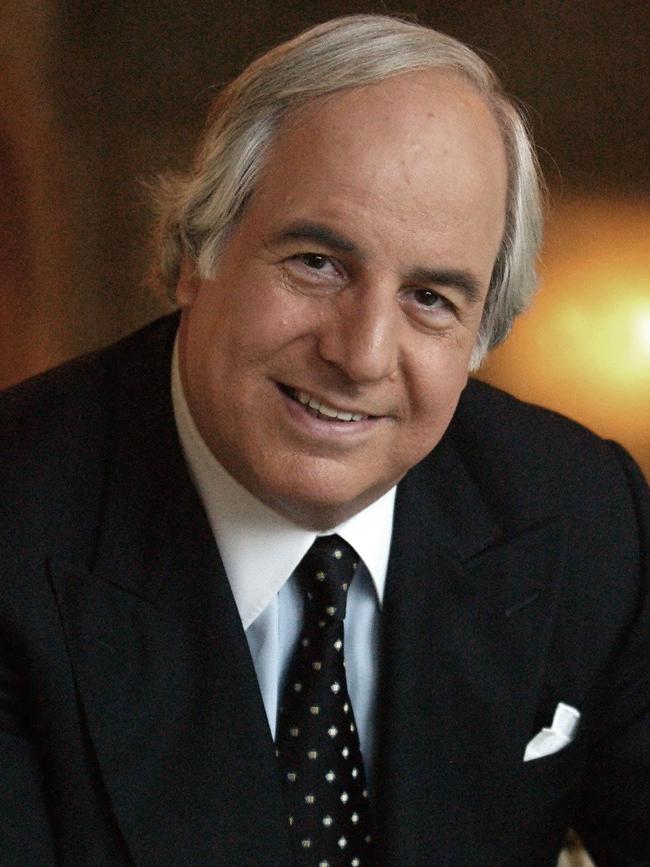

The exploits of Frank William Abagnale Jr are so extraordinary they inspired the film Catch Me If You Can, starring Leonardo DiCaprio. After starting his con artist career at just 15, Abagnale convincingly posed as an airline pilot and a paediatrician, then passed the Louisiana bar exam despite never studying law. His luck ran out at 21 with jail stints in France, Sweden and the US, but he then reinvented himself with a legitimate role as a security consultant. “In the old days, a conman would be good looking, suave, well dressed, well-spoken and presented themselves real well,” he told Wired in a 2017 interview about his past and cybercrime today. “Those days are gone because it’s not necessary. The people committing these crimes are doing them from hundreds of miles away.”

Alan Conway and David Hampton lived on different sides of the Atlantic but shared a flair for fraud. Englishman Conway passed himself off as director Stanley Kubrick in the 1990s, cashing in on the name and enjoying backstage chats with genuine celebrities, while American Hampton scammed meals, money and accommodation by claiming to be the son of actor Sidney Poitier in the 1980s. While Kubrick became aware of the impostor and had to live with the worry of what was being done in his name, Conway said he “drew a great deal of strength from him”. “I really did believe I was Kubrick. I enjoyed being Kubrick — great part for anybody to ever have.” Hampton’s story inspired John Guare to write his successful play Six Degrees of Separation — news of which had Hampton “p---ed”. Failing to see the irony of his comments, he told New York magazine: “I thought it was a pretty low and shallow and disgusting and cruddy and seedy thing to do. You don’t take someone’s life story without contacting them.” The play was later adapted into a film starring Stockard Channing, Donald Sutherland and Will Smith.

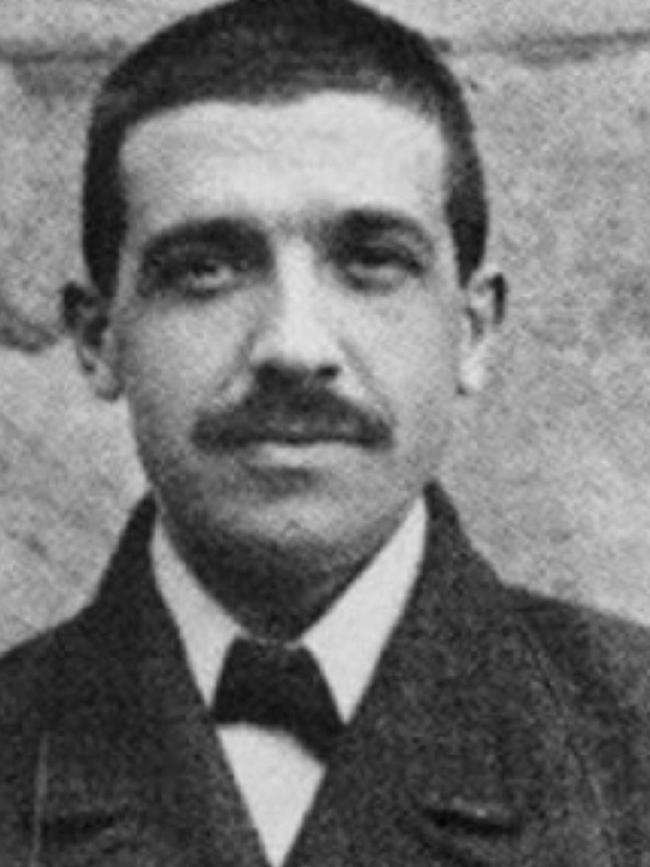

THE SCHEMERS

Swindler Charles Ponzi’s con trick became so synonymous with him, it’s now known as a Ponzi scheme even though he didn’t invent it. The Italian said he arrived in the US in the early 1900s with just $US2.50 to his name after gambling away his savings. It would be more than a decade later, with a patchy work record and a couple of jail stints behind him, that he hit on his money-making plan, luring investors with the promise of quick and large returns on the trade of international reply coupons, used in overseas mail. The money he took from new investors was used to pay generous returns to earlier ones, sparking an investment frenzy, but while Ponzi lived large, the coupon trade at the centre of his scheme was a dud. When the Boston Post started asking hard questions about the plausibility of his operation, investors panicked. Ponzi tried to brazen it out, but the revelations about his dubious financial status kept coming, and in August 1920 it all came crashing down. Ponzi would serve prison time and eventually be deported back to Italy. His investors had lost millions.

About 90 years after Ponzi was raking in the cash, Bernard Madoff pleaded guilty to another robbing-Peter-to-pay- Paul scheme that cheated his victims of as much as $US65 billion. The Wall St investor was sentenced to 150 years’ jail after telling a New York court: “I knew what I was doing was wrong, indeed criminal. When I began the Ponzi scheme, I believed it would end shortly and I would be able to extricate myself and my clients.” But that proved impossible. “As the years went by I realised this day, and my arrest, would inevitably come,” he said. Madoff’s scheme collapsed when too many of his clients wanted to cash in their investments during the 2008 financial crisis and he didn’t have the funds to pay them, but last year FBI agents involved in the case said the crime had been running for a staggering 45 years.

THE HEADLINE MAKERS

Con artists generally want to keep their schemes out of the news; often the less visible they are the more successful they can be. But in the case of the Hitler diaries there was always going to be a media sensation. Editors thought they had the scoop of the century, when Gerd Heidemann, a reporter for the German magazine Stern, turned up 60 journals supposedly written by Adolf Hitler, but in fact created by forger Konrad Kujau. Initial verification attempts suggested the papers were real and Kujau was paid handsomely. But he would end up in jail after the diaries were exposed as fakes within a couple of weeks of being published in 1983. Heidemann, who negotiated the sale, maintained he didn’t know they were forgeries, but was himself jailed for fraud for inflating the cost to Stern and pocketing some of the payment for himself. Ten years ago he claimed to be a scapegoat in the scandal, telling of “envy and schadenfreude” among his colleagues. “Almost everyone who wanted to finish me is dead. But I’m still alive,” he added defiantly.

It was an unfolding crisis that had the world holding its breath. A homemade helium balloon had been released in Colorado and a six-year-old boy was trapped inside as it soared across the sky. Police and the National Guard were in a desperate pursuit, but when the balloon finally came down, the boy was nowhere to be found. Reports that something had been seen falling from the balloon sparked a new, heart-stopping search. But little Falcon Heene had never been in the balloon — after the drama unfolded he was found hiding in the attic of his home.

What later emerged was an alleged plan by parents Richard and Mayumi, former participants on reality TV show Wife Swap, to build media interest to make the family “more marketable” for other TV opportunities. Questions started being asked when, in a TV interview, Falcon commented: “We did this for the show.” But, while the Heenes pleaded guilty over false reports to the authorities, Richard said in 2014 they only did so in the face of threats that Mayumi could be deported. “It was never a hoax. Not once, not ever,” he said. “I took the guilty plea to save my family.”

Originally published as From landmarks for sale to Balloon Boy: 10 crazy cons