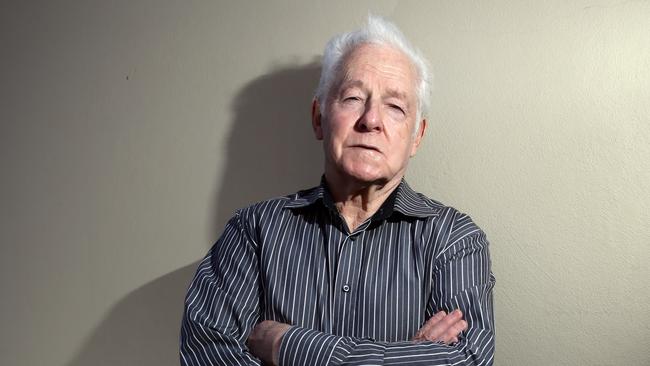

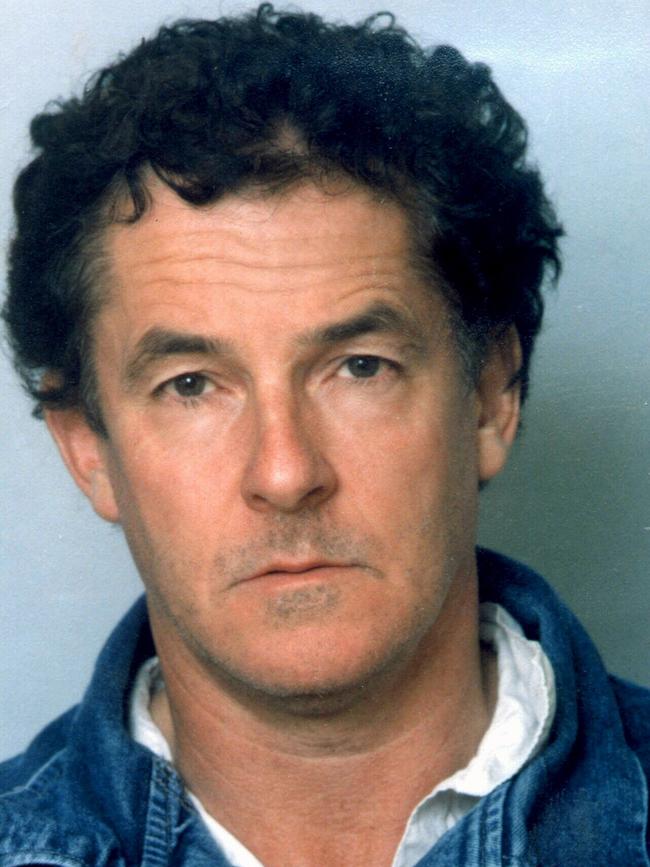

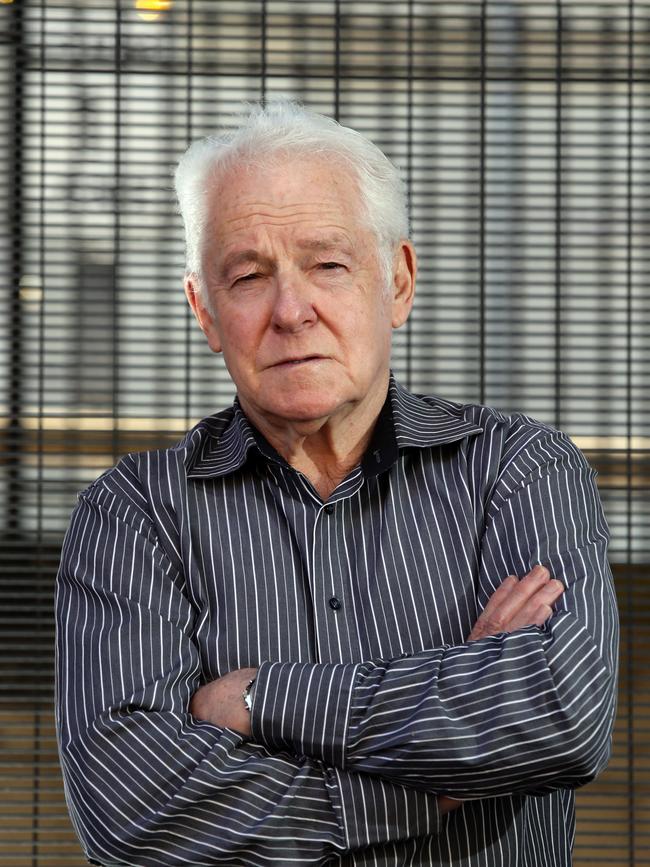

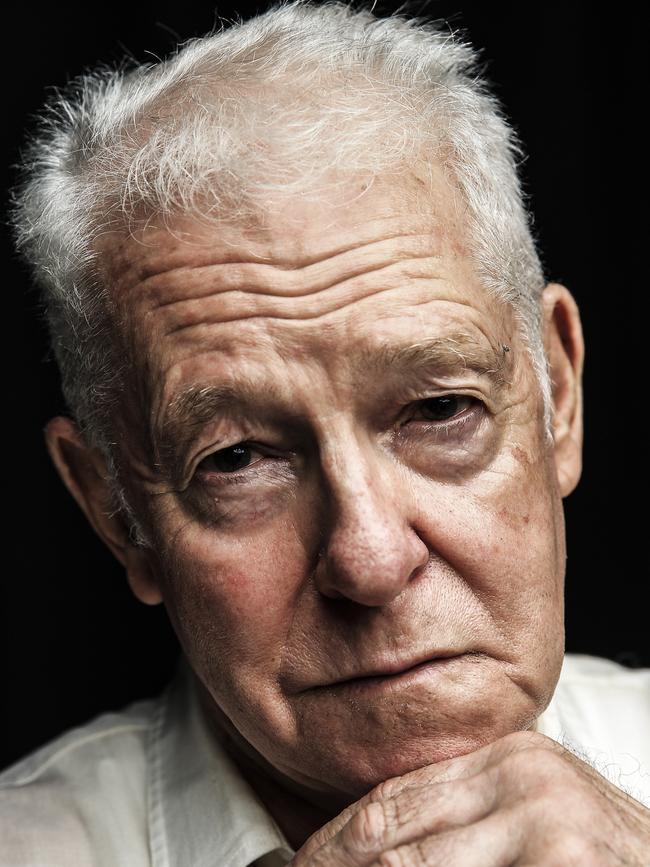

John Killick tells of jailbreak girlfriend before ‘Red Lucy’

Armed robber John Killick was famously busted out of jail in a hijacked helicopter by girlfriend Lucy Dudko in 1999, but in the early ’80s there was another girlfriend drawn into his life of crime — and another dramatic escape.

Book extract

Don't miss out on the headlines from Book extract. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Armed robber John Killick was famously busted out of Silverwater jail in a hijacked helicopter by girlfriend Lucy Dudko in 1999.

But in the early ’80s there was another girlfriend drawn into his life of crime — and another dramatic escape.

True Crime Australia: ‘Red Lucy’s’ daughter Lucy Dudko makes doco on mother’s gun-toting exploit

In his new book, On the Inside, Killick, offers up anecdotes about serving time in some of Australia’s toughest jails and the characters he met inside — from last man hanged Ronald Ryan to Neddy Smith.

He also tells of his three years with girlfriend Jackie, from their shoplifting cons and life on the run to serving time and the shocking moment she helped him escaped his armed guard.

BOOK EXTRACT: I first got to know Jackie in 1980 when I was in Yatala Labour Prison, South Australia, in 1980. She came to the gaol with her mother who was a kind of good Samaritan from the local Bethesda Church.

Her mother included me on her list of prisoners to receive a goodwill visit as my family was in New South Wales and could only afford to visit me now and again. At the time of my meeting mother and daughter Jackie was sixteen and I was thirty-eight. Although her mother June was vastly overweight, Jackie was slim and athletic.

In December 1981, after quite a few visits from Jackie and her mother, I was released and flew home to Sydney, where I renewed my life with my wife Gloria and my six-year-old son; although, things were not good with the marriage after three and a half years of separation. Although the High Court had quashed my convictions I had a chip on my shoulder about having spent those years in gaol away from my family for crimes I hadn’t committed. (Now thirty-eight years later, everything taken into consideration, I feel that I have broken about even with the justice system.)

Early one morning about four months after my release there was a knock on the door. When I opened the door, I saw Jackie standing there. She had a black eye.

‘I’ve had a row with my boyfriend,’ she said. ‘I don’t know what to do. I don’t want to go back to South Australia.’

Gloria was equally surprised. She did know Jackie, as on the occasions when Gloria had visited me in South Australia she had stayed with Jackie and her mother. That, I surmised, was how Jackie knew Gloria’s address in Sydney. So, Jackie was invited in and became part of the family, in more ways than one. Within a month I was involved in an affair with her. Wrong move Killick.

TRUE CRIME AUSTRALIA: The home of the nation’s most compelling crime storytelling

When Gloria found out about the affair she kicked us out. I had an old Kingswood and about $500. Deciding it was best that I should drive Jackie home to Adelaide we set of on the 1600-kilometre trip.

Halfway there she said, ‘I don’t want to go back there, I want to stay with you.’

‘There’s no way we can survive without money,’ I told her. ‘If you stay with me we will have to survive by shoplifting.’

Jackie didn’t protest at the suggestion. In fact, she took to shoplifting like a duck to water.

We would buy packets of Skippy Corn Flakes (the ruse didn’t work with Kellogg’s, which came in a different-sized box) from ten different supermarkets, take out the cornflakes and drop them outside a Salvation Army or mens’ shelter. Then we’d later return to each shop where I’d walk in with a little two wheeled canvas covered trolley containing the empty cornflakes carton with double-sided cellotape attached to the top flap. Jackie would follow at a discreet distance checking to see if anyone was aware of what I was doing. In those days most of the supermarkets had steel cabinets inside one of the aisles containing cartons of popular cigarettes. I would grab cartons of cigarettes from a cabinet and pack them into the empty corn flakes packets. I could get five cartons into one packet before sealing the flap with the double-sided tape. Then, to ensure no-one was onto the scam I’d walk to the breakfast cereal section and put the cornflakes box containing the cigarettes back among the other cornflake cartons. I would then watch Jackie as she picked up the precious carton and follow her to the checkout to ensure she wasn’t being followed.

In those days there were no electronic scanners, the checkout girls would simply look at the price on the packet and put it through the register. Jackie always kept the packet under her arm so they couldn’t feel the weight. She would walk out of the shop with five cartons of cigarettes (fifty packets) for the price of two packets of cornflakes.

She would later do the rounds of small shops selling half-price cigarettes. Her excuse, in case anyone asked why she was selling them so relatively cheap, was that she’d won them in a raffle and she didn’t smoke. She soon built up a regular team of buyers. The ‘won a raffle but don’t smoke’ routine salved the conscience of ‘honest’ shopkeepers.

One guy, a Greek, said to her, ‘You win a lot of raffles.’ By now Jackie was exuding confidence. ‘Oh well, if you doubt my word I won’t bother you again,’ she said and began to walk away.

‘No, I believe you,’ he said. ‘You are just a lucky girl. Every raffle you win no matter how many cigarettes, you bring them to me.’

We moved on to other towns from South Australia to Queensland. For over twelve months we made thousands of dollars profit a month. But expenses were high — motels, restaurants, clubs and of course the racetracks, where I lost more than I won. It couldn’t last. The police finally caught up with us in Merrylands, in Sydney’s west, in 1983. They only had us for a small percentage of what we had stolen in the past year. They released Jackie and I took the rap for making profits from stolen goods. I spent three days in Long Bay before being granted bail. Eventually I received a bond for it because the authorities weren’t aware of how long we had been operating.

TRUE CRIME AUSTRALIA: Confessions of a notorious Aussie safebreaker

PICTURE SPECIALS: Policing in the ’50s | ’60s | ’70s

Cornflakes and cigarettes were out — stamp albums were in. Jackie was a fast runner. She would go into a shop that specialised in stamps and ask to look at the most expensive album they had of Australian stamps. We had a good buyer. He was only interested in Australian stamps. Jackie would drop the album into a bag and run away. No-one ever followed her. But in time the buyer told us to drop off for a while: the philatelist businesses had been warned about a ‘fleet footed young woman’.

Unperturbed we drove to Adelaide. There weren’t a lot of philatelist shops there. The one we decided on was in a quiet, leafy little suburb. Not a lot of people around.

I dropped Jackie of near the shop then parked about 80 metres away near a corner street. The plan was that when I saw her run out of the shop I would drive into the side street and she would be able to jump into the car within ten seconds. I had even changed number plates in case someone did chase her and note the number. What we weren’t anticipating was that the ‘fleet footed young woman’ would be caught before she reached the vehicle. But when she ran out of the shop the old proprietor was close behind her screaming blue murder. Two young guys who were walking towards her grabbed hold of her. Although she began to struggle, they held onto her.

I had brought a pistol with me and could have rescued her at gunpoint but I would have been crazy to have done it. Even with false number plates, our brand-new red rental car would be on the six o’clock news. It was one thing stealing a stamp album, but holding three guys at gunpoint to rescue the girl who stole it would put us in the league of Bonnie and Clyde on the run in the city of churches.

So, I watched them drag her back into the shop. She was looking across in my direction wondering why I wouldn’t help. I knew she would get bail. She was an Adelaide girl who had tried to steal a stamp album.

I waited for her at the motel. She arrived just before the six o’clock news. Thankfully she wasn’t on it. She was upset that I hadn’t come to her rescue and she told me ‘enough is enough’. But she still wanted to come back to Sydney with me.

Back in Sydney she was now on the run. We had to be careful. It was time to try to earn a living legally. We found a flat in Glebe, an inner-city suburb, and put up a bond with what was fast becoming the last of our money. We bought some small baskets, chocolates and nuts. After filling the baskets, we tied little bow ribbons around them and she did the rounds of pubs and restaurants. She made good sales from guys who thought the baskets would be a good gift for their wives or girlfriends. A few of them tried chatting her up, but she was pretty streetwise by now and knew how to extricate herself from tricky situations.

We made enough to survive. I curbed my gambling and she was happy playing housewife instead of travelling around the country while we lived by our wits. There were no motels, restaurants, clubs and new rental cars. She was happy to cook meals while I made porridge for breakfast. She told her mother by phone where she was because her mum wanted to send Christmas gifts. Instead she sent the police. Jackie was taken back to Adelaide, via the Mulawa women’s prison in Sydney. It should have been me going to gaol, but the police weren’t interested in me.

Within two weeks I said to myself, ‘Stuff this.’ I rented a car and drove up to Queensland for the specific purpose of robbing a bank. On arrival I used a street directory to check out banks in various suburbs, looking for a good getaway route. The one I chose had a small arcade I could run through when exiting the bank, leading to an open grassy area where I could jump a fence and run to the car in the next street. It would take a good athlete to catch me.

The next morning, after parking the car in the chosen street I walked to the main road to where the bank was situated. I was wearing transparent gloves and had a shopping bag which contained a mask, a pistol and an aerosol can of paint. At the entrance I put the mask on and entered the bank, pistol in hand. There were four or five customers facing the counter. Three tellers were busy — no-one had taken any notice of me. Moving quickly, I placed a chair under where the camera was situated and standing on the chair I sprayed the camera with the aerosol can. I then walked towards the counter with the pistol in my right hand.

‘This is a hold up! I’m here for the bank’s money. Everybody stays calm.’

The customers turned to look at me. No-one panicked. Placing the bag on the counter I told the first teller to fill it up. The first teller usually held the most money. As he was piling the money into a bag an old lady among the customers turned and started walking to the door.

Stepping back, I pointed the pistol at her. ‘Sorry, madam,’ I said, ‘you can’t leave yet. Stay where you are.’

She stared at me in my mask and said, ‘Certainly not! I’m going home.’ And she just walked out through the door.

I had visions of her outside yelling, ‘Robbery! Robbery!’

I had to get out immediately. No time to collect from the other tellers. (Apparently the old lady meant what she said and went home. The police never managed to find her.)

When the teller handed me the bag I ran out of the bank, slipping the mask off as I exited. Running through the arcade and across the open area I jumped over a fence, then jogged to the car. I looked around — there was no-one in sight.

I didn’t see the nurse sitting in a vehicle four cars back from mine. I was unaware she had noted the registration of my car and written it down. I drove south over the border into New South Wales and booked into a motel on the outskirts of Ballina. I was disappointed that the robbery had netted only $11,000. I figured the old lady walking out had probably saved the bank another $10,000.

The next morning, I read in one of the Queensland newspapers that police were looking for the car I’d rented! When the nurse who had written down my registration heard about the robbery she had contacted the police. I have no idea why she took my number to start with. Did she fancy me?

In desperation I phoned the rental car company and reported the car as having been stolen. Then, leaving the car in a parking area I walked into Ballina. I found an advertisement for a car, a mini, that the seller wanted $800 for. The deal was quickly done. For the seller it was cash in hand.

As I drove to Sydney I tried to come to grips with the fact that my life would never be the same again. Police would know that the car had been hired by a man with a history of robbing banks. They wouldn’t buy the ‘car had been stolen’ story.

Moving out of Glebe I took Jackie’s belongings to a storage unit. Resolving to never commit another armed robbery I threw the pistol into the Parramatta River. I found new accommodation in Ryde sharing a house with a lady named Kerrie, a pleasant lady in her thirties. She had a boyfriend who often stayed overnight. As long as I paid the rent she didn’t ask questions.

As 1984 approached I looked back on 1983 as a horror year. My father had died, Jackie was in gaol and I was wanted for bank robbery. A friend in Adelaide informed me that Jackie had been sentenced to six months for the theft of the stamp album. He had visited her and reported she wasn’t coping too well. She couldn’t understand why I hadn’t come to see her.

I had no choice. I paid $2000 for a Ford Fairlane and drove to Adelaide. At this stage I figured the Queensland police would hardly anticipate me visiting Jackie in gaol in South Australia. They probably didn’t know of her existence.

When I saw her, she looked terrible. Dressed in a prison suit that was two sizes too large for her she looked pale and drawn. And her hair had been shaved. She burst into tears. ‘I caught lice and they shaved my hair.’

Security was lax. Only one door, locked from the inside, separated the visiting room from outside the prison. Two female guards were the only obstacles.

‘I can bust you out,’ I whispered. I meant it. I was responsible for all of this. I was wanted for bank robbery, why not add a gaol break to the list?

‘No, John. With remissions I’ve only got three months to go.’ She brightened and gave me a brave smile. ‘I will be okay if you stay in Adelaide and visit me every week.’

I spoke softly. ‘I can’t — I’m wanted for a bank robbery in Queensland.’

She forgot about her own troubles. ‘You have to be careful until I get out. If they catch you I may never see you again.’

I arranged for my friend to visit her regularly to reassure her I was okay. I sent her money and we corresponded by mail using my brother’s address.

Jackie was released two weeks earlier than expected. When I came home I found her sitting in the lounge room. Instead of a warm greeting she gave me a hard stare. ‘What’s going on? Who’s the floozy you’re living with?’

What a contrast she was to that quiet teenager I’d first met with her church-going mother in Adelaide. I laid her suspicions to rest and her and Kerrie became friends. For a while we lived quietly. Police were setting little traps for me, occasionally placing members of my family under twenty-four hour surveillance. No doubt they would do the same in Adelaide with Jackie’s family. By now they had made the connection between Jackie and me.

Time to leave. But where to? Our funds were now under a thousand dollars. Melbourne was the logical choice. But I decided to be clever: where was the one place they wouldn’t expect me to go? Queensland; back into the lion’s den where I was wanted for bank robbery! What a brilliant move!

With Jackie following me in the mini we drove to the sunny state. Ironically, listening to the radio on the way I heard Queen’s latest hit ‘I Want to Break Free’ so many times that I couldn’t get it out of my mind. It was to prove prophetic.

Booking into a motel at the Gold Coast we thought about the money we had made in the past and agreed that the cigarettes scam had been the most profitable. With cornflakes off the menu we used empty Ry-Vita biscuit packets: two Benson and Hedges cartons fitted perfectly inside.

It worked for a while but it was a slow process getting two packets at a time compared to five in the cornflakes box. It took most of the day to earn $200. We began to yearn for the Skippy Cornflakes days.

And then Jackie got caught. As they took her back inside the supermarket, where I had no doubt they would call the police, I tried to remain calm. It was only a minor charge — she would be bailed and later fined. But if they connected her to me they might hold her. I doubted they would check her out to that extent, a girl taking two cartons of cigarettes. But better to play it safe. Her mini was parked outside our motel. She was carrying the rego papers. If they found it they would check with the motel and get the rego of my vehicle. Either I dump both vehicles now or I move the mini. I couldn’t afford to lose both. I had $800 and might need that for a lawyer for Jackie.

The motel was on the other side of the city. It took me an hour to get there. After driving her mini about a kilometre away I parked it in a block of units and jogged back to the motel. What I didn’t know was that the police promised Jackie bail if she could provide them with an address where she lived. You can’t be bailed without an address. She had given me an hour’s start then provided the motel details.

While I was packing our belongings ready to leave, the police arrived. When I walked outside they were waiting — with weapons drawn. I was taken in handcuffs to police headquarters where the armed robbery squad were waiting for me. They led Jackie past me, also in handcuffs, and she gave me a wink. I winked back. I knew they were going to use her as a bargaining chip.

They were determined to throw the book at me.

‘We’ve got you for six banks, John,’ MacDonald the detective in charge said.

I laughed. I had only been to Queensland a few times. But they were serious.

‘It’s up to you,’ he said. ‘We know you did them. Either give us a statement admitting to the robberies or we charge her with being an accessory. We can hold her without bail until the trial. Don’t you think she’s had enough?’

I knew they would probably nail me for the bank I had robbed. The nurse had gotten a good look at me as well as taking down the registration of the rental car. They would add a bit of good old-fashioned verbal to seal my fate. At that point in time verbal was still a powerful weapon in Queensland.

‘I’ll give you a written statement on the one where the woman took the number of the car,’ I said, ‘if you let Jackie go without charge.’

‘Done deal,’ he said. ‘We’ll still charge you with four and put the other two on some other bastard’s brief.’

True to his word, after I gave him the statement, he released her without charge. I knew I had just signed myself up for about ten years regardless of what happened with the other three charges of bank robbery they put on me.

I was sent to Boggo Road Gaol and Jackie was allowed to visit me. She was upset and in tears. ‘It’s my fault they got you,’ she said.

‘Don’t blame yourself. They would have got me sooner or later.’

‘I’m going to get you out. I just don’t know how.’

From what I had seen of Boggo Road maximum-security prison, the odds of escaping from it were extremely long. There were a lot of desperate men imprisoned there who would undoubtedly escape if they could.

I tried to persuade Jackie to return home but she refused. Living on the dole and the money from the sale of the two cars, she rented a room close to the prison. She wrote every day and visited me twice a week. Sometimes she became so depressed she talked of suicide. I was depressed myself. Boggo Road wasn’t regarded as one of the hardest prisons in the country without good cause. Facing a decade there would depress anyone. I had devised a plan to escape. I would have to get to a hospital where Jackie could slip a weapon to me. I gave her the name and address of a mate in Sydney who owed me a big favour. When she met him and told him she wanted me out of gaol he gave her a shotgun. She hid it under the bed where she was staying.

‘I’ll use the shotgun to get you out when you go to hospital,’ she said, but I told her it was far too big. They would notice it and shoot her. Instead, I told her to go back to Adelaide, get hold of a replica pistol, paint it black and drill out the blocked-out hole in the front so the entire weapon looked real. ‘I will get word to you when I’m due to go to hospital.’

Before Jackie returned to Adelaide she managed to get hold of the replica, but the police were, in the meantime, still asking her questions about me. ‘We think he’s up to something — what do you know?’ they asked her.

After she reluctantly returned to Adelaide I worked at getting to hospital. I was born with iritis; if I didn’t eat the correct foods and vitamins my eyes became inflamed to the point where I couldn’t open them. I began starving myself, surviving on only bread and weak tea. I stayed up most of the night and used my eyes reading as often as I could. Eventually my eyes were so inflamed the prison doctor had no choice other than to send me to hospital, but for security reasons they don’t tell you when.

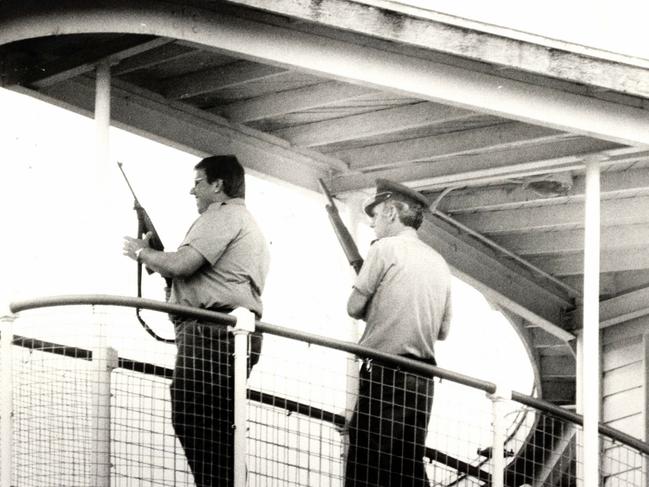

Handcuffed I was taken to the Royal Princess Alexandria Hospital. I noticed only one of the three escorting guards was armed. Important information for my next visit. And when we arrived the driver left us, so there were only two guards — one of them armed — between me and freedom. No high walls, no guards on towers with high-powered rifles. Just two guards.

As anticipated, the specialist prescribed me some Predsol eye drops and told me to return in a few weeks for a check-up. When the guards were making the appointment I deliberately stood away with my back turned. As the nurse handed one of them the appointment slip I spun around and asked to go to the toilet.

‘You’ll be home soon,’ the guard said. ‘You can wait until then.’

I caught a glimpse of the date — 9 August.

It took three days before I managed to see the welfare officer. One of the functions of his job was to make phone calls for prisoners. In those days prisoners had no access to phones. I asked him to ring Jackie and let her know that I had an unexpected court date on 9 August and could she arrange a lawyer. There was a bit of fiction thrown in there, but I could hardly tell him the truth.

On 8 August Jackie visited me. She had flown from Adelaide to Sydney and then driven an old Kingswood to Brisbane carrying the replica and the shotgun.

‘What’s the plan?’ she asked with a big grin. Hard to believe she was only twenty.

I outlined the way it had to be done. ‘You will have to hire another vehicle. Get it for a week. If everything goes okay no-one will see it.’

She was nervous. But she hadn’t come this far for nothing. I knew she would do it.

FOLLOW: True Crime Australia on Facebook and Twitter

When we arrived at the hospital the driver left, as I knew he would. He thought he would be returning later to drive us all back to the gaol. As we proceeded through the hospital towards the eye care clinic a lot of people were staring at us. If things went according to plan they would have a lot more to stare at when I left the building.

Near the specialist’s office I saw Jackie. She was wearing a wig. The plan was to wait until I came out and was near the exit. One of them would go across to the public phone to call for the driver and when I coughed Jackie would make her move.

After a few tests the specialist told me that my eyes had healed. There was no need to come back. Still handcuffed I was escorted through the corridors to the foyer of the main entrance. When we stopped and one of the guards walked across to the phone my heart began to pound. This was it — only one to beat!

I looked for Jackie: she was standing back near a pot plant. I coughed. She didn’t move. She was staring at me, transfixed to the spot. I coughed again, louder. The guard gave me a questioning look. My face must have given me away. I saw the alarm in his eyes. His hand moved towards his jacket where he had his weapon concealed. Simultaneously Jackie rushed forward with the butt of the replica protruding from a newspaper. She thrust it towards me and ran to the exit. The guard was reaching inside his jacket as I pointed the pistol at him and said, ‘Put your hands in the air or you’re dead!’

He stared at me, undoubtedly in shock as he slowly raised his hands. If Jackie hadn’t drilled a hole in the barrel so that it resembled a real weapon he may have called my bluff and shot me. I glanced across at the other guard. He was looking across at us and talking animatedly into the phone.

I spun around and, untroubled by the handcuffs, ran towards where Jackie was waiting in the old Kingswood. As I got in she handed me the shotgun, but no-one had followed me. I had to be careful with it while I was still in handcuffs. If the armed guard had given chase I would have used it to fire at the ground, just to warn them off and emphasise that I was armed.

We drove to the second car, got in and headed over the border into New South Wales, where Jackie had booked a motel. We spent hours using a nail file to sever the chain link of the handcuffs. In the process the left cuff tightened, cutting into my wrist. By morning it was swollen and blue.

To add to our problems our pictures were on the front page of the newspapers. We managed to drive to Port Macquarie unhindered, where we checked into another motel and Jackie went off and bought some small hacksaws. It was painful and difficult but after hours of work we were able to free me.

We stayed on the run, a Bonnie and Clyde type of couple, for nine months. Jackie’s twenty-first birthday was coming up and she wanted to go home. We were on a beach near Melbourne when she asked me if I loved her. We’d been together for three years and I knew that one day I was going to get caught. I didn’t want her with me when that happened. She wanted a life I couldn’t give her.

‘No,’ I said, ‘not the way you want anyway.’

It was better to feel that emotional pain than to be continually looking over our shoulder, wary of people staring at us in restaurants, always carrying a gun with me. I couldn’t go home, but she could as there was no absolute proof that the woman in the wig who had helped me escape from the hospital had been Jackie. Even if convicted, she’d probably do a year and then she’d have her whole life ahead of her.

Jackie looked at me for a while when I said ‘no’. She said nothing, then nodded her head, stood — and walked away. It was over.

During our nine months on the run I had robbed three banks. I still had about $10,000 remaining. I handed her $4000. ‘When you go home get a lawyer and with your family go to the police. Ask them if they want you. I doubt they will arrest you; they will hope you will lead them to me.’

‘I would never do that.’

‘I know. But they don’t know that.’

She did go to the police with a lawyer. But they didn’t want her.

I returned to Coogee, a beachside suburb of Sydney and rented a place there. For a while I lived a quiet life. But I was gambling heavily and after a bad run I decided to rob another bank.

On 20 May 1985 — ten days before Jackie’s birthday — my luck ran out. I’d stolen $16,000 in the robbery at Mona Vale but never got to spend it. I was arrested that night at Newport when I tried to give Gloria my car before I took off to Melbourne. I was taken to Long Bay and charged with three bank robberies. When Jackie found out, I learned she had fainted. She few over to Sydney to visit me in gaol and you’d never guess what she suggested.

‘I can bust you out,’ she said.

‘Forget it, Jackie. Put it out of your head.’

I knew that they would probably arrest her now that they had me. I advised her to go to my solicitor, Bruce Miles, and tell him that she wasn’t involved in the Queensland escape. They only assumed it was her because she was a regular visitor. In reality they had no hard evidence because the woman wore a wig and all that the guards had seen was the back of her head.

But Jackie didn’t make it to Bruce’s office. She was arrested and extradited to Queensland where she pleaded guilty to aiding and abetting my escape. She received a two-year prison sentence and was released after nine months — serving most of it in Adelaide where she could see her family and friends.

Jackie came to see me in 1988, four years after the escape. We had a good chat and she promised she would come to Queensland to testify for me at my trial when I was extradited there after my sentence in Sydney expired. As expected, MacDonald was there to arrest me on my release. We few back to Queensland, with me in handcuffs.

After spending six months on remand at Boggo Road the Supreme Court gave me bail and I returned to Sydney. My lawyer had contacted Jackie about testifying for me at my trial. Jackie dropped a bombshell — she had recently married. Her husband didn’t want her travelling to Queensland to testify in a trial.

I hired a car and drove across to Adelaide to see her. She showed me her wedding photos. I had to admit she made a beautiful bride. After a few Bacardis for old times’ sake and a lot of reminiscing she agreed to give evidence for me. I gave her a coffee machine for a wedding present.

‘What will I tell my husband?’

‘Tell him you won it in a raffle.’

We few her up for the trial and put her in a nice hotel. But three charges were dropped due to lack of evidence. I pleaded guilty to the one robbery and was handed two and a half years imprisonment with immediate parole. I was free. Jackie few home without having to testify.

The last time I saw her was in Adelaide in the mid-nineties. She looked great. She had come a long way since she wore that wig in the hospital.

• On the Inside, New Holland Publishers, RRP $29.99, available from all good book retailers or online www.newhollandpublishers.com

Originally published as John Killick tells of jailbreak girlfriend before ‘Red Lucy’