Why 7000kg of hair made Auschwitz- Birkenau camps in Poland so profound

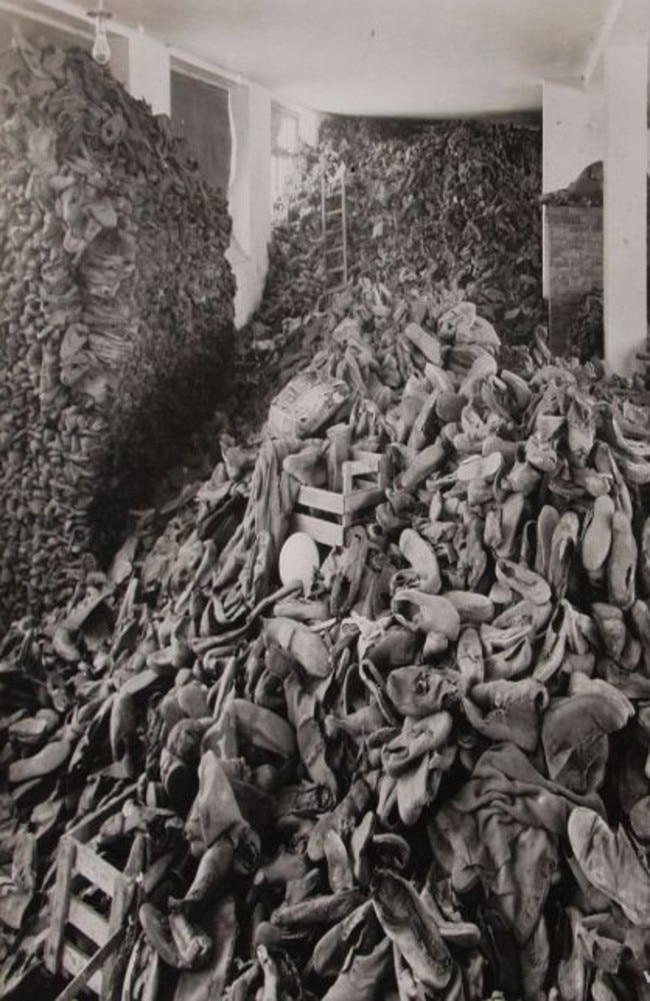

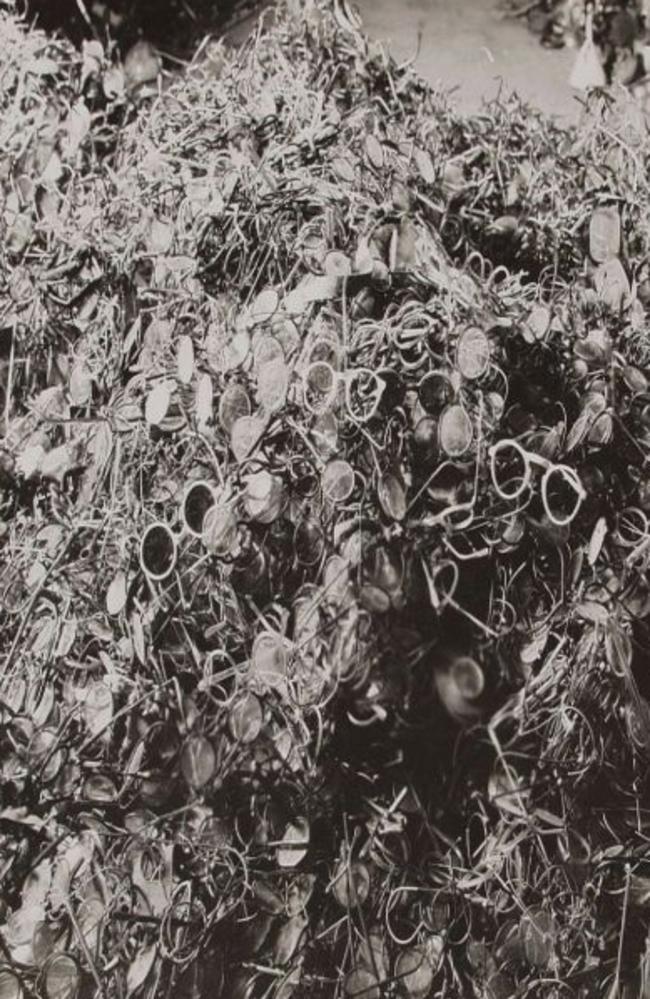

The hair made the biggest impact. It just sat there limp and lifeless. All 7000kg of it. But the huge piles of spectacles, shoes and hairbrushes humanised the holocaust in unfathomable ways.

Travel

Don't miss out on the headlines from Travel. Followed categories will be added to My News.

The hair made the biggest impact.

It just sat there limp, lifeless.

All 7000kg of it.

Each strand found after liberation so aptly represented the thousands of lives lost at the three concentration camps outside the town of Oscwiem in Poland.

Most people know the camps as Auschwitz or Birkenau.

They have become symbols of terror, genocide and the holocaust all over the world.

But it wasn’t just the hair. It was the piles of spectacles, the unfathomable collection of shoes and artificial limbs, and the hundreds of hairbrushes, shaving-brushes and toothbrushes.

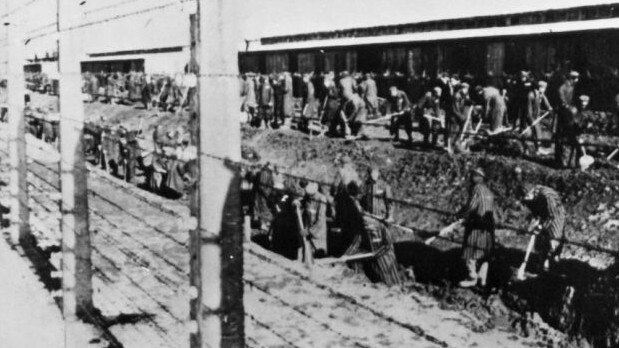

The people who arrived at the camps on the overcrowded trains from all over Europe, many of them believing they were on their way to a better life, were parted from these possessions and many more as they were marched to their deaths.

There are no words to aptly describe walking through the gas chambers and crematoriums where hundreds of thousands of people, mostly Jewish, died.

But it is essential to fully grasp the magnitude of those fateful years.

The impetus for my journey to Auschwitz was the book Elli, a novel by Livia E. Bitton Jackson about her introduction to womanhood amid the atrocities of the Polish concentration camp run by SS soldiers.

After a year of studying Elli for Year 12 exams, it became a mission to get to Poland to make sense of the horror.

The Auschwitz memorial and museum is essentially just buildings but the powerful imagery etched through that book brought the ghastly story to life.

The high expectations about the profound effect the camps might have were marred somewhat though.

The eeriness and the horror were less palpable than anticipated because the sheer number of tourists and school groups dampened the experience.

That aside, the piles of belongings tell a story no book can share.

And the hovels these people were expected to live in with little more than body warmth for comfort – if they were “lucky enough” to be plucked from the lines leading to the death chamber for medical experiment purposes or slave labour – becomes real as you walk their path.

The camp was originally established to cater for the mass arrests of Poles but it soon became the largest of the death camps, accounting for some 1.3 million deaths.

About 1.1 million of those deaths were Jews.

Only about 7500 prisoners awaited liberation when Soviet soldiers found the camp. They found the corpses of another 600 prisoners who succumbed to exhaustion or were shot as the SS withdrew.

While you can buy a guide and make your own way around the concentration camps, it is worth the money to hire headphones for a group tour where you all tune into your guide.

Do not miss the movie at the start showing footage of the camp and its inhabitants at liberation.

It is heart-wrenching – especially seeing the young children who have trouble remembering their name because they have been identified as a number for so long.

The next overwhelming moment is the mocking message at the gates of Auschwitz I “arbeit macht frei” (work brings freedom) which the prisoners would pass under each day after 12 or more hours of work.

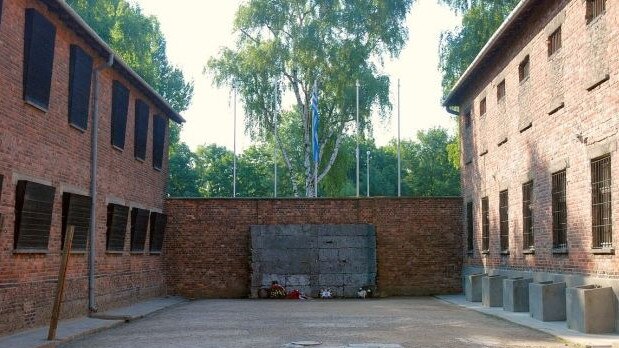

In this camp, the stories of medical experiments and punishment in the “death block” are horrific.

The guide book says a prisoner could be punished for anything from picking an apple to relieving himself during work hours to bartering his own gold tooth for bread.

Punishment varied from flogging, hanging, suffocation in cells with little oxygen, extra toil or the death penalty.

This is also where they first built and experimented with a gas chamber and crematorium which they then honed and enlarged at Birkenau.

You will see the haunting faces of those who died throughout the buildings.

Take note of the date they arrived at the camp and died – the gap ranges from a few days to months.

There are also sheets of paper which record their deaths mere minutes apart – listing varying fictitious reasons instead of the stark reality of the gas chamber.

The most important remains at Birkenau are the remnants of four crematoriums, gas chambers and cremation pits, the unloading platform where the deportees were selected and a pond with human ashes.

When you stand at the end of the railway line between the gas chambers at Birkenau and look back towards the entrance, there is a strange feeling of familiarity.

Though there are still many who deny genocide took place, that image of Jews being marched to their death has been firmly planted in the psyche of those educated about the Holocaust.

If you look beyond the bricks and mortar, even a day following and reflecting on the cruel and oft final journey those prisoners took can be overwhelming.