Aussie scientists are using cutting edge forensic techniques borrowed from crime scene investigators to determine the health of our oceans, with potentially massive implications for the global fishing industry – and even what seafood we eat.

A state of the art laboratory called OceanOmics will officially launch at the University of Western Australia this Thursday, building up a comprehensive library of the estimated 5500 fish and vertebrate species that frequent Australia’s oceans.

The lab is the latest ambitious conservation project from Andrew and Nicola Forrest’s Minderoo Foundation.

WATCH EXCLUSIVE VIDEO BELOW

While ‘Twiggy’ earnt his reputation (and billions) from land-based enterprises, marine conservation has taken an ever-increasing focus for the mining magnate.

He has bought Tasmanian aquaculture interests, campaigned against overfishing, called for a moratorium on all deep-sea mining at the recent COP27 conference, and even completed a PhD on a depleted marine species, the short fin mako, in 2019.

The OceanOmics program “aims to revolutionise ocean conservation through the development of next-generation genomic tools … for the monitoring and management of ocean wildlife, including endangered species,” according to the Minderoo Foundation.

The researchers are using a technique called environmental DNA (eDNA) analysis to determine what’s actually out there in the deep – and crucially, in what sort of numbers.

Currently, estimates of marine species’ health are based on observations, or catch – methods which can be unreliable.

It’s been estimated that more than half the global seafood haul is from fish stocks with insufficient data to determine if they’re sustainable or not.

The Australian government monitors 477 individual fish stocks in our waters, and the latest report shows 302 of those species are sustainable.

But 37 of the fish stocks are depleted, another 17 are characterised as “depleting,” 36 are recorded as “negligible catch” and for 70 there is insufficient information to make an assessment.

In other words: for 160 of the 477 monitored stocks (just over one in three), warning signs could or should be flashing.

On the depleted list are such favourites are blue swimmer crab, Tasmanian scallops, and several stocks of snapper.

But with 65 per cent of the seafood eaten in Australia coming from overseas, the OceanOmics research has the potential for a global impact, not just a national one.

Working like a sort of Crime Scene Investigation Marine Unit, the OceanOmics team will detect what species of marine life have been passing through a certain location based on the DNA samples they leave behind. Fishy fingerprints, if you like.

“eDNA can really revolutionise how we measure, understand and ultimately protect the ocean,” said OceanOmics director, Dr Steve Burnell.

“When you consider the conservation range of threatened or endangered species, eDNA can be a very powerful tool telling you that [a species] is in these other areas where you thought it was perhaps not present. Or vice versa, it can be quite powerful in telling you [a species is] absent from an area where it once was quite common.”

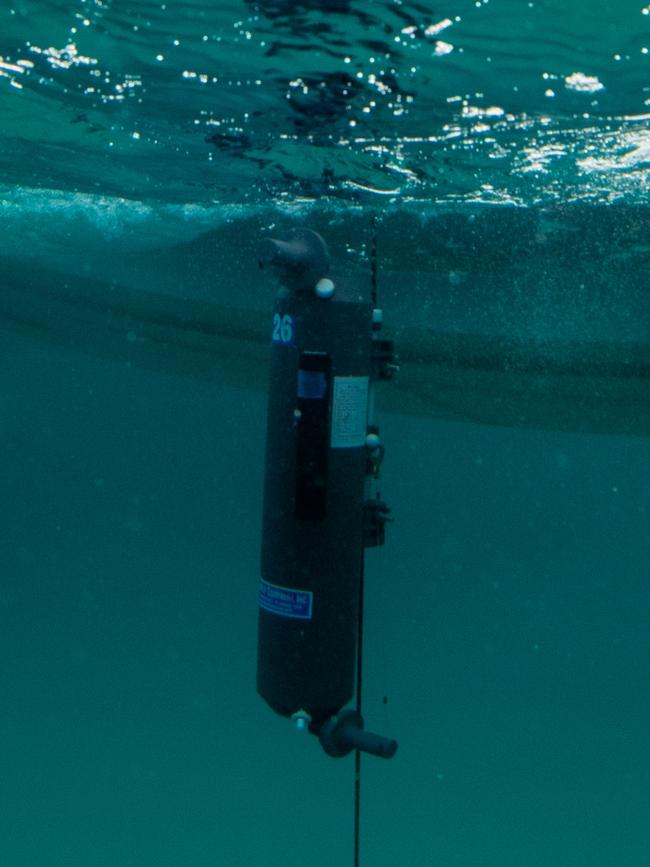

The eDNA samples are collected via tubes of sea water lowered to different depths.

The sea water is then run through filter paper, which collects all those telltale DNA signs of a marine species’ presence – everything from tiny corals to the big behemoths of the sea.

The samples can be analysed back at OceanOmics, which will be the biggest marine genomics lab in the southern hemisphere, or on board the research vessel Pangaea, which comes equipped with its own full laboratory.

The team can take a “scattershot” approach, to look at the full field of what’s in the sample, or target their search for specific marine creatures.

The samples can also be used to determine the abundance or scarcity of a species, with this data hopefully being used in future to guide what the fishing industry take from the sea.

Analysis on board Pangaea, with its rapid turnaround time for results, means the crew can do additional testing in the same or nearby waters, should surprising results pop up.

It also means they can monitor the real-time effects of marine heatwave events – an increasingly frequent phenomenon in Australian waters – to see which species suffer, which species survive, and which species change their behaviour or range as a consequence.

“Going to those locations and sampling the eDNA during that time means we can assess what is happening within that biological community while that stressful event is taking place,” said Dr Priscilla Goncalves, a marine biologist with OceanOmics.

“We can study how the population responds to that heat event, but also how it recovers it over time.”

Currently docked at Fremantle, the Pangaea’s next expedition will take it around the Cocos Keeling Islands, one of two Australian Indian Ocean territories nestled close to Indonesia.

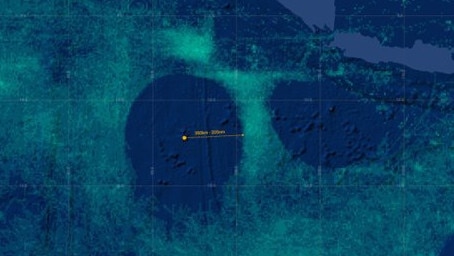

Satellite imagery from the website Global Fishing Watch shows the immense fishing pressures in at play in the region: trawlers largely avoiding the Exclusive Economic Zones around the Christmas and Cocos Keeling Islands, but intensively working other areas, including a narrow strip between the two zones.

The OceanOmics team will be studying the marine biodiversity of the region, as well as the wider effect of such concentrated fishing activity. “We’re excited about the potential for eDNA to provide supporting data for the sustainable management of those fish stocks,” said Dr Burnell. “It’s really a game changer for conservation.”

While the OceanOmics eDNA program will be focused on practicalities like the impacts of overfishing, climate change and ocean acidification on our marine environments, there also remains the possibility the researchers will discover new species, or even find ones thought lost which are still hanging on.

“Many of these species are small, they’re cryptic, they’re not fished or easily observed, so finding them via eDNA can give us some encouragement that they are still there,” Dr Burnell said. “But of course, they may still be horrendously threatened.”

David Mills visited the OceanOmics facilities in WA as a guest of the Minderoo Foundation.

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

Bushfires force residents out of home

Several large and slow-moving bushfires have engulfed parts of the state, with emergency services ordering residents out for their safety.

Homes still without power as floods loom

Emergency crews have responded to more than 100 calls for help as destructive winds, flood warnings and snow loom over Australia's south, leaving thousands without power.