AFTER three hours of intense, high-pressure football, it came down to this. One kick and a huge pack of players waiting where it dropped. Now was the time for heroes.

IN the West Coast coaches’ box John Worsfold couldn’t afford to look away.

As his assistants around him yelled out ‘kick it Coxy, kick it’, he glanced at the clock _ 10 seconds to go. He then looked towards the city end of the MCG. If the Eagles were to be a chance, he needed three players to be in the goal square.

He needed his best marker, Ashley Sampi, a man who treated the turf like a trampoline. Yep, he was there.

He needed his tallest overhead marker, Mark Seaby. Yep, he was there.

And he needed the best player on the field; someone who could do anything, anywhere at anytime: Chris Judd. Yep, he was there.

“Right,” Worsfold thought. “We’re a chance.”

“We had a clock in the box,” Worsfold says. “We knew there was no time so I’m just thinking ‘kick it in long Coxy’ and hoping someone will mark it. And we had the players we needed in Seaby, Sampi and Judd in the right spot. I was probably hoping, kick it in and see if Samps can do something here and, if not, Juddy on the ground.”

The man with the ball in his hands felt the panic of a child playing musical chairs at a birthday party.

With West Coast on the wrong side of the ledger, Cox didn’t want to be the odd one out when the siren sounded. He had to keep the ball in play. So that meant he had to get rid of it. Quickly.

The giant ruckman was a natural right-footer but going back off the mark to kick with his favoured foot might leave him stuck with the ball. So, to save the slimmest of milliseconds, he swung around and launched it into the sky with his left boot in the hope that wherever the ball landed something remarkable might happen.

“I didn’t want to get caught with the ball where I was,” Cox admits. “So I just wheeled around on my opposite foot and it was just a matter of getting it in into a dangerous spot.”

It was a beautiful kick.

Whistling through the wind, spinning through the sky, countless eyes locked on 500 grams of leather as it floated towards the goal square.

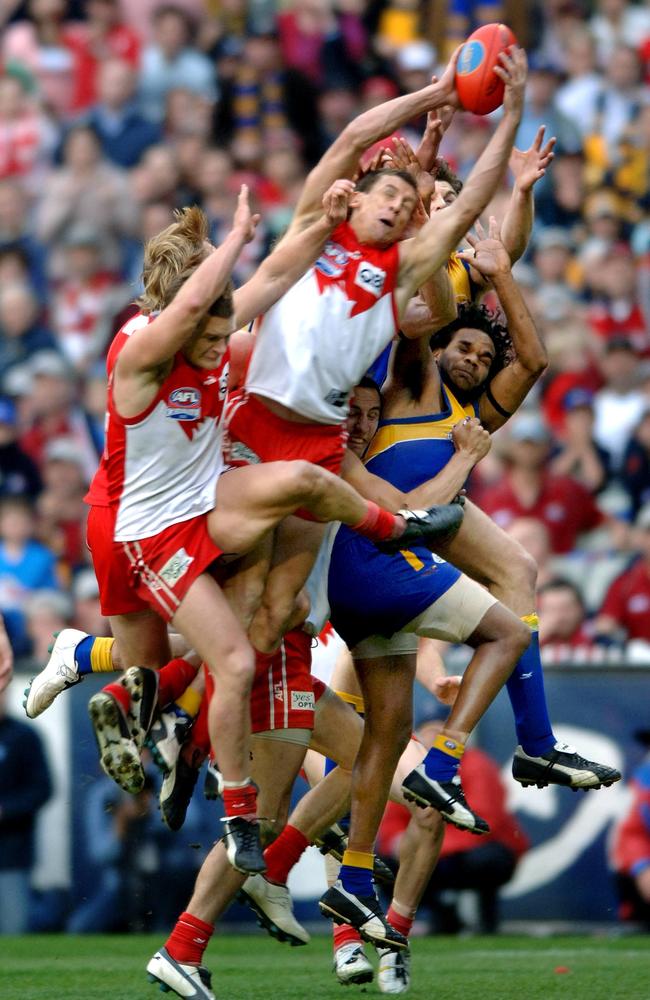

There were nine men in the vicinity of where the ball was heading, five from Sydney, four from West Coast. Another eight players were inside 50 but further away from the action. One of those was Leo Barry who’d actually stayed out in the pocket after he’d kicked downfield to Cox.

Already on the move was Tadhg Kennelly. In front of him was West Coast’s electric forward Ashley Sampi. In 2004 the flying Eagle had taken the Mark of the Year when he jumped so high for a grab he had to be reminded to come down. As Sampi followed the ball in the air all Kennelly could see in his head was a video of Sampi taking another screamer. He had to stop him.

“I saw Ashley straight ahead of me and I remember thinking ‘he’s got mark of the year this bloke’ so I’ve just bee-lined for him,” Kennelly says. “I just went as hard as I could to make body contact with him.”

So the Irishman gambled. Convinced the umpire wouldn’t penalise him at such a crucial moment he grabbed Sampi to stop him doing his trademark jack-in-the-box bounce.

“You look at the vision and I’m clearly holding him,” Kennelly says. “It’s a clear pull, but it would have been a brave umpire to call it.”

Later, when Sampi untangled himself from the pack, he noticed part of his jumper was missing.

Kennelly had grabbed him with such ferocity he’d ripped the AFL Grand Final logo off his guernsey.

The four other Sydney players underneath the ball had the same mentality _ defence. They had to stop a West Coast goal. They couldn’t let this Grand Final slip when they were so close.

Amon Buchanan and Lewis Roberts-Thomson went into self-preservation mode. Buchanan had thrown himself around the field all day so, as the pack formed, he did so again launching himself into the six sets of legs that had already left the ground.

Roberts-Thomson’s thought process was slightly more logical.

“When the ball was kicked out and marked by Coxy I didn’t have a man on me,” he says. “So I was like ‘uh oh, I better somehow influence this because if a bloke that’s free takes the mark I’m going to be in trouble’. It was just like ‘get in there and try and stop the goal’.”

Coming from the southern side of the ground were Nic Fosdike and Paul Williams. Both felt a sense of panic pulse through their nervous system when they saw the challenges in front of them.

Fosdike suddenly found himself trying to stop Mark Seaby. Realising he was outsized he pulled out of the contest to protect the goal.

“I didn’t even fly in the end because I was zero chance of spoiling,” he says. “Mark was so tall. So I stayed at the back and made sure if the ball spilled out I was defensive cover.”

Unbeknown to Fosdike, he didn’t have to worry. As Cox kicked in, Seaby realised it was out of reach.

“I knew I was probably half a step off where I would have loved to have been,” he says. “You can see in the photos that were taken that I’m kind of reaching out in front.”

Paul Williams was playing on Judd, but rather than follow the West Coast wizard into the pack he, like Fosdike, didn’t leave the ground.

“He (Judd) jumped up for it,” Williams says. “I decided to stay down because I just didn’t want it to go over the back. I didn’t think anyone would mark that ball because there was just too many in that pack.

So I just played the percentages and thought I’d protect the back just in case it does come over.”

Foresight also tapped away at the back of Mark Nicoski’s mind. The tireless half-back had been covering Amon Buchanan like a blanket. But, suddenly, when he looked to his left he saw 20 metres of green grass and the goalposts. He glanced back at Buchanan and calculated there were too many men trying to take one mark. So he changed tactics.

“(Amon) flew into that pack and I remember thinking ‘I’m going to stay down here, because if this spills, I’m on my own, I’m going to snap a goal and win the grand final,” Nicoski says. “That was literally what I was thinking.

“There was no way he could mark because it was a hard pack. I knew that if he dropped the ball I would impact the next moment. I can still see the amount of space I had around me, I can still see it now, there was a big circle of grass that if it spilt I would have had at least one or two seconds to grab it, snap it.”

OF the seven players who would leave the ground to battle for the ball, the person who ran the furthest to get there was Leo Barry.

After kicking downfield from the pocket, he’d stayed in place admiring his footwork. But when Cox kick-returned, something caught his eye. The flight of a football.

Throughout his celebrated AFL career, watching a ball spin through the air made Barry move

instinctively. It might be a stutter of short steps, like the start of a fast bowler’s run-up, or the loping strides of a long jumper. But no matter the leg movement, his eyes would stay skyward, fixed on the Sherrin slicing through the sky.

“Having played as a forward in the past, one of my strengths was the ability to read the flight of the ball and know where it’s going to land,” he says.

So when Cox rifled the footy back, Barry saw the bigger picture. Not only could he make it to the ball, he believed he could actually mark it. While the mentality of his teammates was to defend, his was to attack.

“... the only thought I had was ‘I’ve just got to mark it’ - Leo Barry

“From the sprint out in the pocket the only thought I had was ‘I’ve just got to mark it’,” Barry says. “It was that clear and simple. (Taking a mark) was my first and only thought.”

So he started to run. Arms swinging, eyes staring skyward as he tracked that beautiful ball. For 25 metres he blazed across the ground, then, with a leap off his wrong foot _ his left _ he flew through the air.

Having timed his run to perfection, Barry crashed into the pack with his eyes shut, his hands open and his arms stuck above his head as if they’d been set in plaster. And, just as he had calculated, the ball stuck to his hands. Not only that, but because he was the only player coming from the left, the inertia of the other six flying footballers jack-knifed him in the air making his legs snap right. But he refused to let go of the ball. The Sherrin had stuck like superglue to Leo Barry’s magical mitts.

“I literally tried to squeeze the air out of the ball I had that strong a grip on it,” he says.

“I squeezed the absolute hell out of it.”

In the commentary box Stephen Quartermain found the words to match the moment. All game his call had been forensic, analytical, reserved. But when Leo Barry “caught the cup’, for the first time in more than three hours he drifted into the second person when he screamed: “LEO BARRY, YOU STAR!”

Quartermain used four words to describe the moment, whereas Paul Roos only needed to hear three. As he sat in the coaches’ box looking away from the field assistant coach Peter Jonas shouted: “Leo’s marked it!” And then Roos picked up another three words that sounded even better: “The siren’s gone!”

In the post miracle-mark carnage, Barry didn’t hear the siren. The first moment he realised something had happened was when a delirious Tadhg Kennelly jumped on his back and they tumbled to the ground together. Suddenly it became clear, they were premiership players.

There was mayhem at the MCG.

On the field Sydney players dived on each other with delight. In the stands Swans fans leapt to their feet roaring the news that only needed one word to describe: “YYYEEESSSSSS!!!!!!!” Quartermain made it official when he cried: “The longest premiership drought in football history is over. For the first time in 72 years the Swans are champions of the AFL!”

Soon red and white reigned supreme around the stadium. Flags, balloons, ticker tape, even tears. The players wrapped themselves in each other as relief turned to rejoice turned to a realisation of what they had achieved.

At the medal presentation the beating heart of the club, Brett Kirk, grabbed the microphone and shouted: “This is for The Bloods!”

The overall mood was one of emotion. As he walked across the ground AFL boss Andrew Demetriou felt the full force of joy as if it was physical.

“It was unforgettable, Swans Chairman Richard Colless was beside himself,” he says. “I walked out onto the ground with Ron Evans and Bobby Skilton who was crying, tears in his eyes. The emotion was at fever pitch. When I gave my farewell speech (after leaving the AFL) I actually put it as one of my highlights. Incredible memories of what happened after the game on the ground.”

THE Sydney players started their long, lazy lap of honour, but as the party started one player broke free.

It had all become too much for Sean Dempster. Feeling claustrophobic in front of 90,000 people he had to escape the scrutiny. So he slipped away and headed towards the dressing room.

Downstairs, the Sydney players’ family and friends waited patiently for the victorious team to arrive. Sooner than expected they heard the hollow echo of football studs running down the race. Then they saw Dempster rush through the doorway and run to his father. The fragile footballer threw his arms around his dad and buried his head in his shoulder. He was finally free of the expectations he was worried he could never uphold.

“After we won we got our medallions and we were doing the lap around the oval and I just felt pretty uncomfortable so I snuck off,” he says.

“Everyone else was partying with the crowd and I went down the race.

“I hated being out there. I’m a quiet person. For me that was too much. It didn’t feel right.

“For me, at the time, I was a young kid, I probably didn’t feel a massive part of the team. And that whole experience made me feel way too uncomfortable _ I don’t think I’ve told too many people _ but I made a beeline down the race and my parents were down there which was great so I got to cuddle them and that’s when it really started to sink in how great a feeling it was.

“My old man’s pretty tall so I could see his head and went over there and had a cuddle and had a bit of a howl.

“So now my memory (of the match) is probably one of regret, because I didn’t make the most of celebrating or taking in what we’d achieved.”

After another few minutes victory chants and the garbled singsong of happy voices could be heard coming towards the dressing room and _ at last _ the players arrived to collegial cheers from their families.

As a beaming Barry Hall breezed through the doorway he scanned the room and suddenly stopped. In the corner standing quietly was a nuggety figure with a lopsided grin that he knew too well. Hall’s skin shivered with goose bumps. It was his dad. Unbeknown to Barry, Ray Hall had turned up to watch his son skipper the Swans on Grand Final day. It was only the second time he had ever watched him play AFL.

“After the game was a really good moment,” Halls says. “We all went into a room and my family and I hugged it out and cried and did all that sort of thing.

“I’m not sure how dad got there. Mum might have dug him in the ribs and said ‘get your arse to the game’. My sister and brother were there too.

“But I didn’t know dad was there. Not until afterwards. I walked into the rooms and they were all standing there. It was a pretty good moment.”

West Coast’s Chris Judd was awarded the Norm Smith Medal for best on ground but admitted afterwards: “I wanted to win a premiership medal and I didn’t do that today. That’s disappointing.”

After the match his defiant skipper Ben Cousins told the press “this is just the beginning. The best is yet to come”.

They were prophetic words.

“The best” did come for the club when they took out the 2006 Grand Final with a thrilling one-point win over Sydney, their first flag since 1994.

But Cousins didn’t lead them onto the MCG that day. His secret life of drugs and deception had started to unravel, forcing him to relinquish the captaincy.

And it got worse.

Cousins’ illicit cravings would eat into every part of his life, and those who had once been so loyal to him were now leaving him behind.

In October 2007 West Coast would sack their one-time superstar and, a month later, the AFL wouldn’t even let him play the game.

So, just two years after the historic 2005 Grand Final, the once adored ‘Prince of Perth’ found himself on his own. An outcast whose addiction promised him heaven, but delivered him hell.

BACK IN TIME: NOW READ THE FIRST FIVE EPIC CHAPTERS

CHAPTER ONE: BELIEF IN VICTORY

CHAPTER TWO: BLOOD, DRUGS AND BOXING

CHAPTER THREE: THE JUDD-ERNAUT

Top 10: QLD’s best schoolboy football prospects

A Rocky centre dominating in both codes, an Ipswich Grammar x-factor, a school leader set for the Titans, and the son of gun going to the Roosters. It’s the top 10 of our 50 best schoolboy footy prospects.

The 50: Schoolboy champs making their mark

An Ipswich SHS beast heading to Penrith, a PBC backrower snaffled by the Roosters, and a Downlands kid that plays like Ponga. It’s part four of our look at QLD’s best schoolboy footy prospects.