Rabbitohs star Braidon Burns hopes to use NRL profile for good

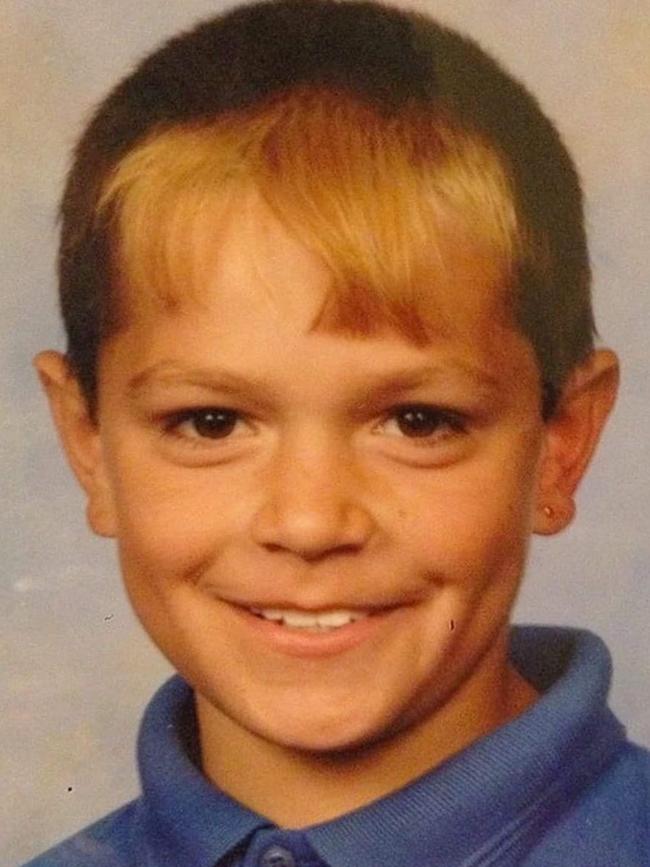

Rabbitohs sensation Braidon Burns has tried hard to escape his childhood after growing up with drug-addicted parents and a father in jail. But it follows him. Like recently, when his mum showed up to training in tears, begging her son for money.

Rabbitohs

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rabbitohs. Followed categories will be added to My News.

Braidon Burns was training at Redfern Oval the other morning when mum showed up. Hand out, wanting cash.

“But I said no,” Burns says. “Wouldn’t give her any.

“And mum, she got real upset. Started crying.

“Which really shook me up. I was struggling. Eventually, I went back inside the sheds …”

But still, the kid stayed firm.

For if you reckon seeing mum in tears is tough, how about overdosed in the front seat of a car?

Slumped unconscious, eyes shut. From one arm, a needle hanging lifeless like her body.

Exactly how old Burns was that afternoon back home in Coonamble, he cannot say.

Just as this son of longtime drug users, and in the case of dad Jonathan Silver, a convicted armed robber, has no memory before those of his home being used by parents, uncles, whoever, to shoot up, throw down or simply celebrate being “out”’.

On that particular day, Burns, still a schoolboy, had no clue about the car parked suspiciously by his house. And so the kid walked down the driveway to investigate.

“Which is when I found mum,” he recalls.

“She’d overdosed, a needle still hanging from her arm. Looking in, I thought she was dead.”

That’s why when Tanya Burns came calling for cash the other day, her boy said no.

Just as he refused that cousin who first offered him drugs, aged 14. And more recently, his old man reaching out from Long Bay.

“Whenever I’m struggling with a decision,” Burns says, “I think of finding mum. Of being rocked, then ringing the police …”

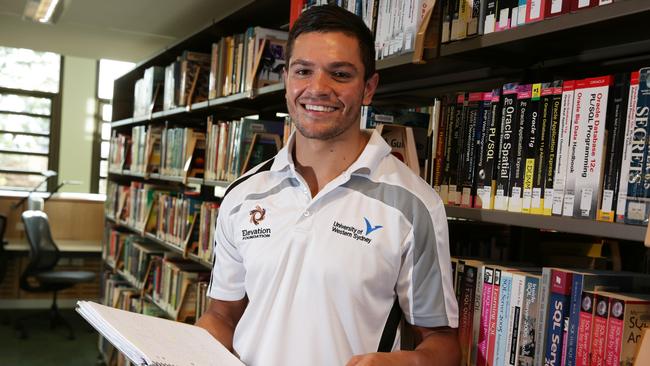

It’s why Burns now wants to be a copper. But only after starring with Souths — understanding the bigger his NRL profile gets, the more powerful his message for change becomes.

More than anything, he wants to bring change: for himself, younger brother Dray and any other kid seeking something other than what they have.

“Growing up,” Burns says, “rugby league was my outlet. First game, I was three. And no matter what else was happening, I could just get out there and play.”

And now?

“Now it’s my way of influencing others,” he says. “And the more popular you become, the more people listen.”

Seated now at a small cafe adjoining Souths HQ, Burns is opening up on the story which, for years, he’s been too embarrassed to tell, at least entirely.

At 22, this rising Rabbitoh is the most compelling yarn in rugby league. Daylight second.

Not only working for charity, or using holidays to visit remote communities — where he teaches diet, lifestyle, even the best way to brush teeth — but also working with police, speaking with indigenous kids via Facebook, even finalising paperwork to become the legal guardian of Dray.

This is not a tale of breaking into the NRL. It’s about breaking cycles.

It’s the story of a scared kid who remembers uncles shooting heroin in his house, family members fighting and him acting out right through primary school — “seeking the attention I never got at home” — before clenching fists to prove himself.

“Because for a long time,” Burns recalls, “I blamed myself for mum and dad being gone.”

And what little boy wants that? Or to upset his mum?

Which is why Burns was so hurt by those tears the other day at training, he eventually disappeared inside the sheds to be comforted by coach Wayne Bennett, himself the son of an alcoholic.

“If mum needs support, I’m there,” Burns stresses. “If she ever comes asking for food, I’ll get it. But still, there’s a line.

“I don’t like giving money when I don’t know what it’s being used for.”

Same deal, dad.

“When I was playing Under 20s, he’d call a lot from jail, promise me all these things. And initially I was naive, thought he’d sort himself out.

“But as you get older, you start to realise how hard cycles are to break.

“So last time dad got out, I decided to give him one last chance. Told myself if he didn’t sort things, I’d move on.

“And then, yeah, he was straight back in. It broke me. I stopped taking his calls and he stopped calling.”

None of which has been easy on the young Rabbitoh, who earlier this month buried grandmother Gail, the woman who raised him, drove him to games, everything.

“Whenever nan was home, none of that other stuff happened,” Burns remembers. “She always kept me fed, made sure I had money.

“So out home, there were plenty of kids worse off than me. I always considered myself fortunate.”

He still does.

“Oh, yeah,” Burns adds, “I’ve got so many people wanting me to succeed.”

LISTEN! In the second episode of his No.1 podcast, Matty drills down on the Keary/Cronk combination, lauds the small forward revolution and tells how the Knights almost sacked him - twice.

Like those two aunties out west who treat him like a son.

And Dave Farrugia, that Coonamble farmer who completed all the paperwork, references, everything, so Burns, in Year 9, could earn an indigenous scholarship to Sydney’s prestigious St Joseph’s College.

“Changed my life,” the centre says.

“I got out of Coonamble and into structure … Joeys taught me things I didn’t know were normal.”

Burns also learned of homesickness, big time. So just before Year 11, and after barely scrounging enough money for a train ticket — “I even walked through the dorm selling my protein powder” — he shot through.

He eventually made it home to an earful from nan, before turning what seemed the worst of decisions into his best.

“I enrolled at St Stanislaus College, Bathurst,” he says, “and met the Roebucks.”

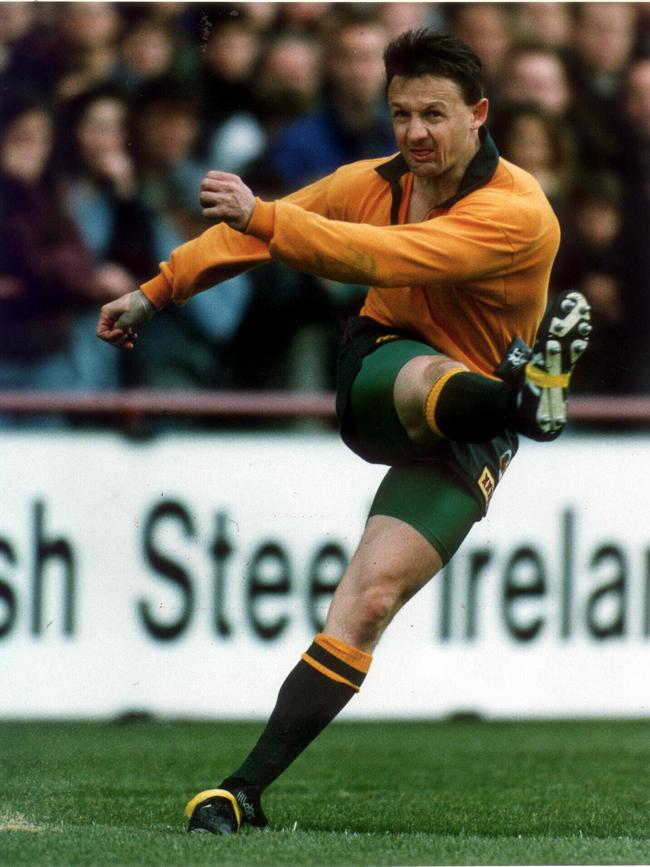

Specifically, old Wallaby fullback Marty Roebuck, wife Su and a family including son Brae — his classmate, footy teammate and now “brother” with whom he shares a Bondi Junction unit.

Ask about Marty, a fella with the drive to not only play 23 Tests and be part of Australia’s 1991 Rugby World Cup triumph, but become a doctor in his 50s, and Burns recounts how before one school interview, he was hauled into a bathroom, handed a razor and told to shave.

Just as when the boys were signed out on weekends, it was on the proviso they hung out as a family, eating pizzas and watching footy on TV.

“First time in my life I’d had rules,” Burns says. “The Roebucks not only treated me as their own, they opened my eyes to how people live.”

It’s a life he now wants for Dray, too. The 15-year-old finds himself at St Stanislaus on the reputation of big brother.

“One of his teachers is actually coming down this week to speak about how he’s going,” says Burns, who is also seeking to become Dray’s legal guardian.

“And eventually he’ll move in down here because being his role model, it’s my motivation.”

Yet, as for saving everyone?

“I just want mum and dad to do their best,” Burns shrugs. “I can never understand what they’ve been through, or what demons they’re dealing with.

“That’s actually been the hardest part in talking about all this. I haven’t been able to ask them what they think because they haven’t been here.

“So now, I’ve just decided it’s best for me to open up. To get this out so other kids can read it, hear it and hopefully benefit.

“Because I’m not embarrassed anymore. This is my story.”

Originally published as Rabbitohs star Braidon Burns hopes to use NRL profile for good