Why Paul Harragon epitomises comradeship driving Beanie for Brain Cancer round, writes Paul Kent

A gruelling trek up Everest base camp for a group of former Newcastle stars holds the key to why the NRL’s Beanie for Brain Cancer round means more than footy, and why Paul Harragon epitomises the concept.

Knights

Don't miss out on the headlines from Knights. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SPORT CON: Eels weigh in as Semi eyes shock return

There is a timeliness about this weekend’s Beanie For Brain Cancer round, one that reaches into your heart and makes you dream of better days.

It probably best begins last year, when Mark Hughes and Paul Harragon and Matt Johns and 25 others are climbing to Everest base camp through the thin air and there came moments of despair and elation and defeat along the way, often within minutes of each other, and with each turn they leaned on each other and helped each other.

This, they knew, was friendship.

Live stream the 2019 NRL Telstra Premiership on KAYO SPORTS. Every game of every round live & anytime on your TV or favourite device. Get your 14 day free trial >

MORE NRL NEWS

AUSSIE SCHOOLBOYS: NRL TEAMS WITH FUTURE STARS

NRL STOCKS: WHO’S HOT AND WHO’S NOT

Several spots on the climb were auctioned to raise money for the Mark Hughes Foundation, which goes towards cancer research, and for their money these men got to make one of the world’s most difficult climbs along with men they had watched and admired playing football together.

That’s how it begins, sometimes. A few men and a shared dream.

And so last year 28 men began the trek up Everest and the guides told them about half would fail to make it but, by the time they got to base camp, every one of them remained.

But it wasn’t good.

Some were slightly delirious, and urinated themselves without realising. Some wandered around camp, vague and detached.

Steve Crowe had a nap and there were real fears he was not going to wake up.

His oxygen levels were about a third of where they should have been and he was urgently put on a tank.

Having conquered their own mountains the team began to settle in for the night when the guide told them that in the morning he was making a further mall climb to Kala Patthar.

It was a peak, he said, that gave you the greatest view of Everest you will see.

They were cooked, though, and went to bed. Nobody wanted to make the climb.

At 4am the next morning Johns was in bed when he heard a knock at his door.

“Chimpy, that you?”

Chimpy is Harragon’s nickname for Johns.

“You know what mate?” Harragon said. “We’ll never be back here.

“We’ll never be back here,” he said again for emphasis, “let’s go and do it …”

Johns climbed out of bed and they began the walk to Kala Patthar, just a few of them this time, and every step needed concentration.

Johns could manage nothing more than walking 10m, resting for 10 minutes, and then going again.

Harragon, his son beside him, would walk a small bit and stop to vomit with altitude sickness and go again.

“Chimpy,” he said at one point, “this is the best day of my life.”

They finally made it to Kala Patthar and to the sun rising behind Everest.

Harragon was gone though. His knees, battling arthritis and letting out small screams, had begun to seize. His thighs were pumped from the climb and not behaving how they should to go the opposite way, the climb down.

When it came time to return Harragon got worried.

LISTEN! Matty’s back with Kenty and Finchy and they run the rule over the Raiders premiership chances, try to understand what’s happening at the Sharks and look back at the ‘89 grand final and ask what would have happened if the Tigers won.

“I didn’t think I was going to make it down,” he said.

Johns watched Harragon turn around and, slowly and agonisingly, begin walking down backwards. It was the only way he could get home.

He looked at him and thought, what a man.

Of course, nobody was surprised when they saw Harragon walking backwards into base camp.

Harragon was always their leader. The one that did what it took to get it done.

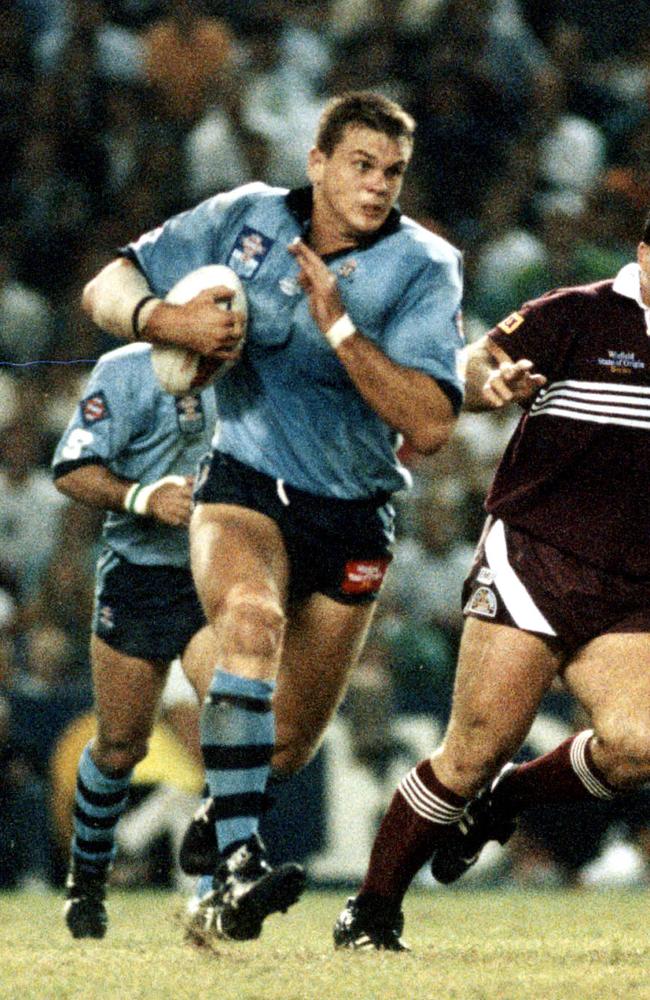

Johns remembers him returning from Origin one year busted and beaten and the Knights were playing Western Suburbs and a sandy haired young second-rower was on the way up and went hunting Chief.

Harragon, as busted as he was, sighed with only one choice.

“He just went him,” Johns said.

It happened often. Players on their way up, old rivals still fighting to stay competitive, all found Harragon because he was the benchmark.

And he accommodated them, every week, without excuse. That was his obligation to his team.

In their own way they all made their sacrifice.

I still remember covering the Knights during that run in 1997 and walking into a dressing room each weekend with the Hunter and Collectors’ Holy Grail thumping through the room.

They truly believed they were marching as one, and it became their anthem. Andrew Johns was at his best. Matthew, too.

Harragon and Tony Butterfield, Marc Glanville and Adam Muir, they played it tough through the middle while out on the wing, in his first season, Hughes shocked everybody with his combination of skills, toughness and footy nous.

He quickly became what the Knights prided themselves on. A teammate others wanted to play with.

What happened in those days has a great timeliness this week.

The Knights found something bigger in each other that, whatever it was, it survives today.

It was there in the dressing room 22 years ago and it was there last year on the walk to base camp and later to Kala Patthar.

They were doing it for Hughes, auctioning their company to help a teammate that fell ill with brain cancer and who in the second chance he was given wanted to help others.

All this week Beanie For Brain Cancer has been the backdrop to the soap opera of NRL football.

The focus for much of the week was on Ben Hunt standing down for the Dragons last weekend, despite being healthy.

Hunt, who plays against Souths on Friday night, was rested after coach Paul McGregor noticed his fatigue on his return from Origin.

McGregor was in a no-win position. Last year he played his Origin stars and wore it for wearing them down. Last round he tried to rest the tired one and the Dragons lost and he got roasted for not playing him.

All the science told him that injuries happen most when a player is fatigued and McGregor was thinking about Hunt’s long term welfare.

Harragon never played in this era of sports science. It might have been a good thing.

Years ago Kelvin Giles, the former Canberra and Brisbane trainer who took his knowledge around the world, sniffed his nose at this modern preoccupation with sports science.

Sports science is meant to improve. Mostly it does.

But in a whole other area, Giles believed, it is pulling athletes away from the realms of their capabilities.

As soon as they get near their limits the experts are resting them, because the science tells them.

How can an athlete expand on what is possible if he never pushes his limit?

The Knights found it in themselves in 1997, and then found it in each other, and it created a bond that exists to this day, and no amount of sports science can manufacture it.

That is what got them through their climb, all these years later. It is what got them home in ‘97, when they were the best in the competition.

Originally published as Why Paul Harragon epitomises comradeship driving Beanie for Brain Cancer round, writes Paul Kent