Sonny Bill Williams’ Bulldogs exit: Khoder Nasser reveals why NRL star defected

Sonny Bill Williams would have been at the Bulldogs in 2008 if it wasn’t for a $1.275m Caringbah house. Khoder Nasser, Anthony Mundine and other key players exclusively reveal the incredible story behind the most infamous exit in rugby league history.

NRL

Don't miss out on the headlines from NRL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

“F--- the salary cap!” Khoder Nasser growled at Bulldogs powerbroker Arthur Coorey.

With this, the wheels were in motion for the most controversial defection in NRL history.

Sonny Bill Williams had purchased a five-bedroom house in Caringbah, for $1.275 million in 2005. With a high interest rate, he was forking out $90,000 a year in interest alone.

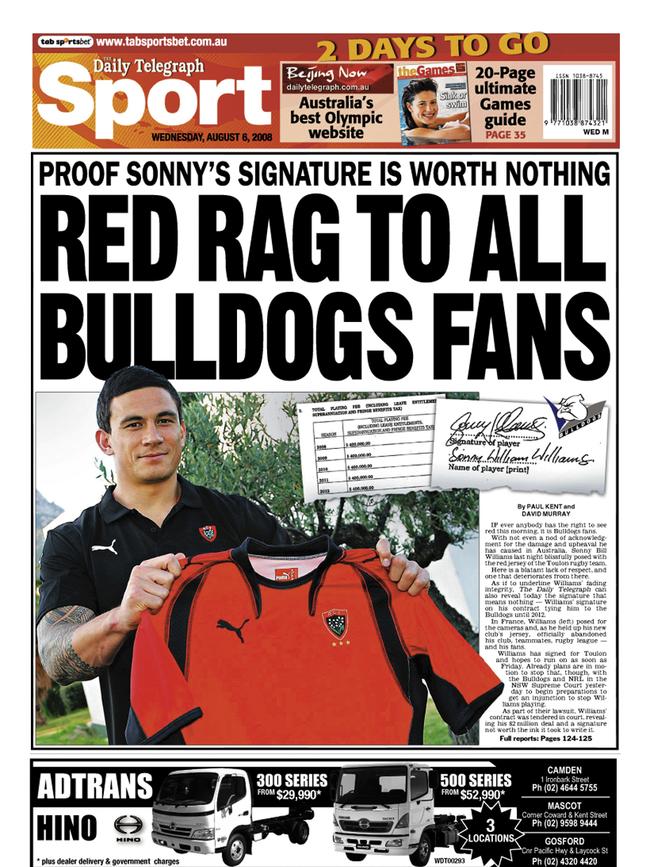

Nasser became Williams’ advisor only after he had signed a five-year contract extension with the Bulldogs in 2007, with the $400,000-a-year deal to run from 2008-12.

Nasser does not deal with banks and opposes home loans with interest, as dictated by his Muslim faith.

Kayo is your ticket to the 2020 NRL Telstra Premiership. Every game of every round Live & On-Demand with no-ad breaks during play. New to Kayo? Get your 14-day free trial & start streaming instantly >

The enigmatic figure had five close friends and family in a circle of trust, with all of them pooling money together and loaning each other cash as needed.

One was his client Anthony Mundine, who earned $6 million in 2006 from his record-breaking fight against Danny Green.

Nasser had held two meetings early in 2008 with Coorey and Bulldogs legend George Peponis at Mundine’s Boxa Bar in Hurstville regarding Williams, who as the highest profile player in the NRL was frustrated by the deal orchestrated by his previous managers, brothers Chris and Gavin Orr, despite having signed it months earlier.

The $90,000 interest was now at the heart of the grievance.

And so here were Nasser and Coorey exchanging frank words, flanked by Peponis, Mundine, fellow sports star Solomon Haumono, the Bulldogs’ new chief executive Todd Greenberg, and Canterbury Leagues club boss John Ballesty at Le Sands Restaurant in Brighton-Le-Sands.

“Pay him his deal up front,” Nasser said. “That way he doesn’t have to pay interest, he can look after himself and his family.”

Coorey and Nasser could talk more bluntly than others at the table. In 1957, when Nasser’s grandfather migrated from Lebanon, he lived in the same Campsie house as Coorey’s father. The pair had history that also allowed them to argue without holding grudges.

But right now, there was no budging on the subject of Williams.

Just six years after the Bulldogs had been fined $500,000 and stripped of all 37 premiership points for salary cap breaches, Coorey made it clear they could not make any moves in breach of the salary cap.

MORE NRL NEWS

Sonny Bill Williams Roosters salary revealed

This is why NRL bent rules for Sonny Bill

Seibold delivers three names after troll probe

Revealed: Two NRL rivals chasing Souths star

“F--- the salary cap,” Nasser replied, exasperated that after paying tax and interest alone, one of the most marketable athletes in the country was no better off than a miner earning $140,000 a year.

The Bulldogs had promised in the previous meetings that a third-party deal would be arranged to alleviate the problem with Williams’ hefty interest rate.

Three weeks went by, then four, then five.

Had the deal come through to allow Williams to pay off his mortgage, he would have remained at Canterbury.

“Then my phone rang,” Nasser recalls. “The guy said he was Tana Umaga, he was the coach of Toulon and he wanted Sonny to play rugby there. I’d never heard of the guy to be honest, I thought it was one of the boys playing a prank, so I told him I’d call him back in five minutes.

“I rang Sonny and asked, have you heard of a guy named Tana Umaga? I’ll never forget his response: ‘That’s an All Black legend’.”

It all became real.

The seventh week was the meeting at Le Sands.

Still no third-party deal.

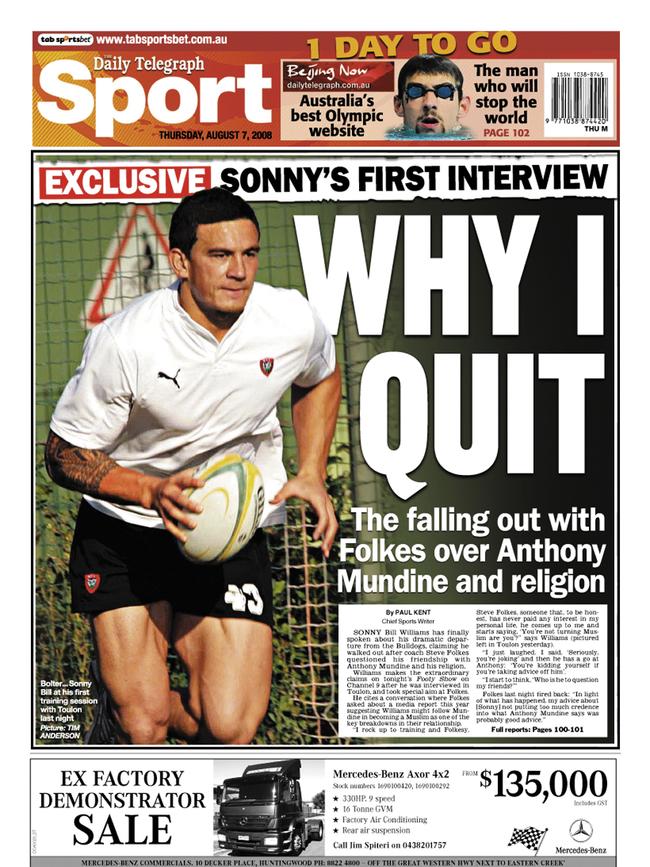

But plane tickets had arrived from Toulon, along with a two-year contract offer worth around $1.2 million.

The clandestine plan was hatched to send Williams away on a flight on Saturday, July 26, two days before the Bulldogs were due to play St George Illawarra.

Just 48 hours prior, Williams and Greenberg had a one-on-one conversation about his future at the Bulldogs, as speculation swirled that the superstar would walk out on the club.

The morning of the infamous flight, Nasser and Coorey met at The Langham in Miller’s Point, then known as The Observatory Hotel.

Overlooking the sunlit harbour, Coorey told Nasser: “You know, the contract is airtight”.

Nasser replied: “I know”.

He left, holding on to the biggest secret in Australian sport, and began the drive up the freeway to Newcastle, where Mundine would be fighting the following Wednesday night, against an opponent whose name, Crazy Kim, was apt for the time.

But Mundine wasn’t in Newcastle. He was helping Williams load his suitcase into a car.

“Sonny is a very grounded fella, but he was adamant about what he was doing, and he never wavered,” Mundine said.

“He followed what was in his heart. A lot of people would rather just be comfortable, not go outside the realm, but what happened with the Dogs and the way it happened, from my perspective he just wanted to get away from the Australian public eye and showcase his talents.”

Mundine drove Williams to the airport, where they were met by Nasser’s brother Ahmed, who would fly with Williams to Toulon.

Greenberg, who’d only been at Belmore for six months, arriving after Williams had signed his deal, was stunned to receive a call from radio host Ray Hadley on that Saturday afternoon, asking if Williams was boarding a flight to France.

Hadley had been tipped off by a customs officer at Sydney Airport, who had been told by Williams he expected be out of Australia for “eight months”.

Greenberg rang Nasser to ask if this was true.

“Yep,” Nasser replied. “Sonny’s sick of this, he’s going”.

Greenberg told colleagues that day he knew Williams was not going to return to the club.

His mission was to recoup as much money from the player as possible.

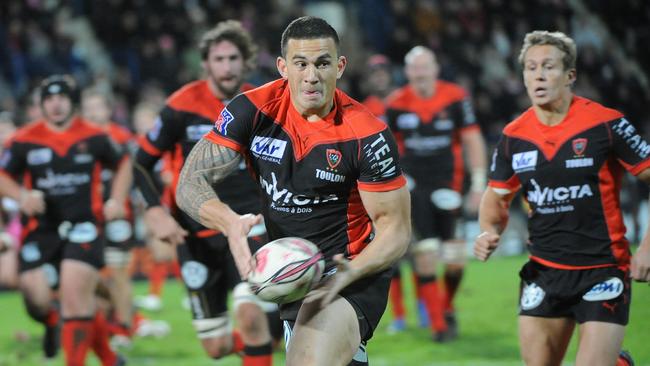

Williams arrived for his first day of training at Toulon with helicopters hovering above the ground and men throwing subpoena papers at him over the fence.

The Bulldogs and the NRL had launched legal action to prevent him playing for any team, and the NSW Supreme Court issued an injunction which, had Williams ignored and played in a looming trial match, could have seen him face jail time back in Sydney.

Williams sat out the match.

The circus was in overdrive.

Labor Party powerbroker Graham Richardson, watching from a distance, had seen enough.

He called Nasser, who he’d known for years, and told him firmly: “The world doesn’t work like this.”

Nasser’s hard edge softened. He agreed to allow Richardson to act as an intermediary and broker a deal with Greenberg and Peponis.

In the end, the figure was $750,000 to be paid by Williams to the Bulldogs in order to be free.

Trouble was, he had nowhere near that kind of money in his bank account, nor was he going to be taking out another loan charging interest.

In stepped Mundine, transferring the entire amount to Williams.

“I knew I was going to get it back,” Mundine said.

“There was an enormous amount of trust, I know Sonny is a very good guy, the honesty he has.

“Lucky I had the money, it didn’t take long before I got it back because he was getting paid well.

“He’d do the same for me if the shoe was on the other foot, that’s how I looked at it.

“At the end of the day, what’s money? Money doesn’t make you happy. If you can help someone who is as close as Sonny is to me, I’ll do it, I’d give the shirt off my back to a stranger if I had to. It’s about humanity.”

RETURN TO THE ROOSTERS

As part of the release, Williams also could not play for a rival NRL club for the full term of his deal unless the Bulldogs were paid an additional $400,000 per season by the new club.

That clause expired in 2013 and Williams returned to the Roosters, having made a handshake agreement with boss Nick Politis prior to his departure.

“We connected through Khoder, it was a shame what happened with the Bulldogs but I told him, ‘If one day you want to come back to rugby league we’d love to have you’,” Politis said.

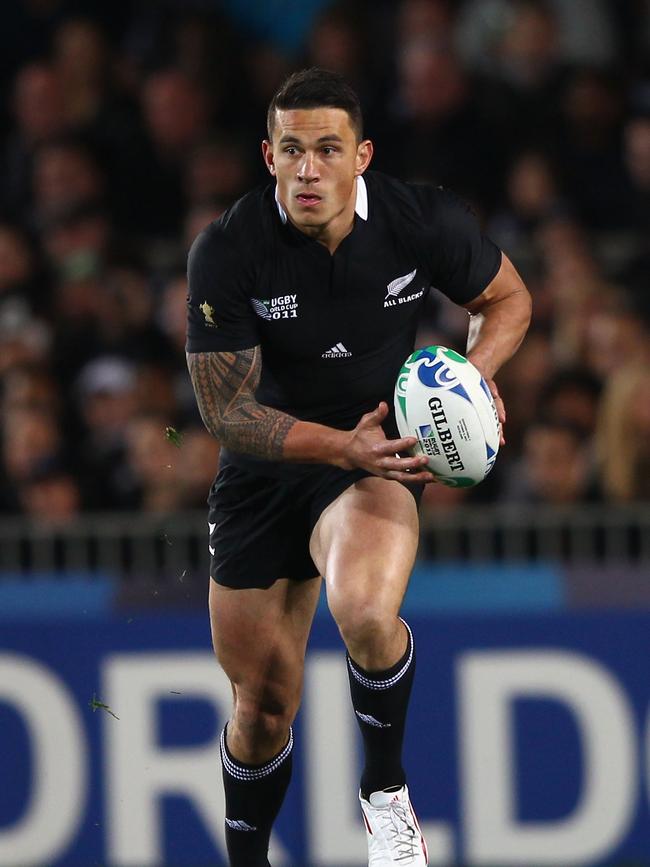

Williams defied the odds, joining the All Blacks to win the 2011 Rugby World Cup, then winning a Super Rugby title with the Chiefs in 2012, before returning to the NRL in 2013.

Upon his return, Greenberg, who was then the NRL’s general manager of football, set up a coffee meeting to clear the air.

“He came back at the same time as Trent [Robinson], who is a great guy and great coach, and bringing Sonny back brought in that aura,’ Politis said.

“A lot of players look up to him, he sets such a high standard of professionalism at training, and when he turns up, he turns up to work, not to muck around or carry on like some players do.

“That professionalism flowed on to a lot of people in the club.”

Williams led the Roosters to the NRL premiership in his first season back in league since his 2008 walkout.

Mission accomplished, he’d return to rugby in 2015, winning a second successive World Cup before heading to the Rio Olympics for the Kiwi Sevens rugby team. An Achilles injury in the first match ruled him out for a year, before Williams returned to campaign for a third straight World Cup trophy last year, only to fall short as the All Blacks were defeated by England in the semi-final.

Then came the $10 million, two-year offer from Toronto Wolfpack that Williams couldn’t ignore.

Living in Manchester, Williams made the 40-minute drive to St Helens on February 22, to watch his old Roosters teammates defeat the hosts in the World Club Challenge, by which time the United Kingdom had three confirmed cases of COVID-19.

Williams caught up with Greenberg, Politis, and chatted to his old coach.

“There was a lot of doubt overseas over whether the [Super League] competition was going to start and whether Toronto would stay in the comp, Trent mentioned that to him back in February when we were over there, he came to our game when we played St Helen’s in the World Club Challenge final,” Politis said.

Indeed, three weeks later the tournament was postponed.

Then the Wolfpack withdrew from the season on July 20 citing “financial challenges”.

Williams was holidaying with his family in Spain when he received the call from Robinson asking him to return for the end of the season, amid a horror injury toll within the Roosters ranks.

He’d already booked tickets for France, Bosnia, Turkey, Greece and Italy.

Instead, the 35-year-old chose to return to the NRL, enduring a mandatory two weeks of quarantine at a Sydney hotel and regular Zoom calls with Roosters players and coaches to learn plays.

“Everything he does, he looks at it as a challenge,” Politis said.

Money wasn’t discussed until Williams had returned to the country.

Such was the trust between Politis and Nasser, when the Roosters owner handed him Williams’ contract over lunch, Nasser put it in his pocket without looking at the promised amount on the letter, $150,000.

“He didn’t come back for the money,” Politis said. “Robbo threw a challenge at him.

“And when the opportunity came, he took it on as a challenge, he didn’t think ‘I’m going to get paid’, because what we’re paying him is nothing compared to what he was earning.

“He thought, what a great challenge, to come over and play for the Roosters after winning a couple of premierships, it would be great to come over and see if we can do it again, that’s his personality.”

Originally published as Sonny Bill Williams’ Bulldogs exit: Khoder Nasser reveals why NRL star defected