Is it a bird? Is it a plane? No, it’s Jonty Rhodes: the first cricketer to fly

At the 1992 World Cup photographer Jim Fenwick captured “Superman’’ in an invisible green cape. Jonty Rhodes explains how the image defined his career - and was even used in efforts to end Apartheid.

Cricket

Don't miss out on the headlines from Cricket. Followed categories will be added to My News.

- Seven questions to define World Cup bid

- Smith and Warner now ‘quiet achievers’

- The ‘groundsman’ set to eclipse Lillee

They say you can’t capture Superman but Jim Fenwick got him in broad daylight with one push of a button.

A push which not only changed a man’s life but the way a country looked at it’s sportsmen and the way a sport looked at itself.

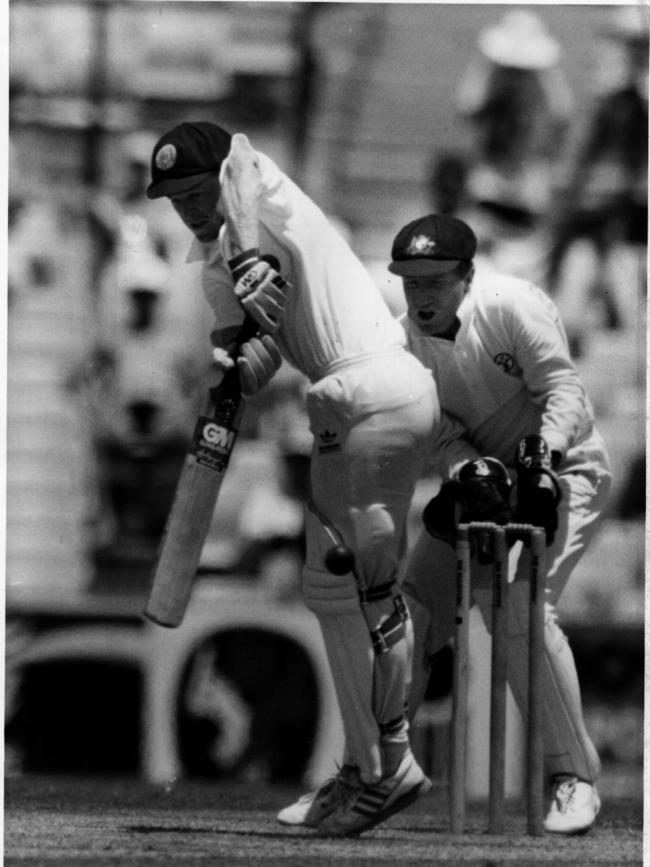

Twenty seven years ago at the Gabba, Queensland Courier-Mail photographer Jim Fenwick was on duty in a World Cup match at the Gabba when he caught “Superman’’ in an invisible green cape.

On March 8, 1992, South African fieldsman Rhodes effected the most celebrated run out in the history of the game when he sprinted from point, and dived head first to skittle all three stumps with the ball in his hand to run out a stunned Pakistan batsman Inzamam-ul-Haq, who had contemplated then abandoned a quick single.

It was such a stunning piece of work it was almost as if Rhodes was destined to fly out of the picture and around the world like a cricketing Peter Pan.

The photo ended up on a wall at the Wanderers Stadium in Johannesburg. The stunning feature of it was that Rhodes was horizontal, as if he was defying gravity. The first cricketer to fly.

It was the days before copyright became so serious, several cricket gear manufacturers grabbed it and put it on the front of their catalogues as an illustration of the breathtaking game cricket could be.

Shirts were printed exclaiming “it’s a bird, it’s a plane … it’s Jonty.’’

But to Rhodes and his nation, who has been rushed into the World Cup at five minutes to midnight as the brutal apartheid regime was falling, it meant even more.

A POSTER FOR THE ‘YES’ VOTE

“That photo changed my career,’’ Rhodes told News Corp from South Africa.

“There is no doubt about that. What people didn’t realise that at the time of that photo there was a vote coming up to see if blacks should be allowed back into the community (the end of apartheid). Had the vote been “no’’ we would have been plucked out of the World Cup. The only reason we got into the World Cup was that the sports ministry assured Cup organisers the yes vote would get through, which it eventually did.

“So Jim’s photo became the poster for the yes vote. It was on posters which claimed “vote yes and keep Jonty flying at the Cup. Was it the photo that changed history? I’m not sure but it was a photo that left a mark.’’

“I remember the Inzamam day so well. When I gathered the ball I noticed that Imran Khan had not moved at the other end and I just didn’t see Inzamam getting back. I knew the most effective way to cover the two metres was to dive with the ball in my hand.

“I have never run anyone out like that before or since. My fielding was a combination of skills. I was a hockey goal keeper so I used to move forward to cut down the angle as I did that day. And I played tennis so when receiving a ball I would split jump so I could move in either direction.

“But my career changed after that ball and that photo. I was an average first class cricketer with an average batting record.’’

In some ways the photo was a split second in the making. But it had a lifetime of special ingredients from the snapper and the fieldsman poured into the majesty of the moment.

LUCK AND JUDGEMENT

Fenwick, at that moment just three years away from retirement, had for many years been regarded as one of Queensland’s finest photographers with sublime instincts and a great feel for his trade that made him a regular judge on other people’s work in prestigious photographic competitions.

“I was focusing on Inzamam and had the camera on motordrive,’’ Fenwick said.

“Inzamam took off and next thing I saw was this figure flying into side of the frame. Inzamam was trying to get back. I was looking at it on the lens. I held my finger down and all of sudden Jonty appeared in the frame. He was moving so fast that in the frame after I got him all I could see was his feet. I was lucky. You are watching the batsmen because he was the main figure.

“It was the pre-digital age so you never know you have it until a few hours later when the film gets developed. I sent the film back and when I saw negative I was excited because there it was.

“It just stood out. It was all there. The flying fieldsman in focus. I had a South African photographer standing near me and he almost got it but his view was obstructed by an umpire.’’

THE BEST IN FIELD

The South Africans had a special reason to celebrate.

“When our captain Kepler Wessels spoke to us at the start of the tour he said that we may have lacked experience,’’ Rhodes said.

“We had played only three ODI games since apartheid - but we could make up for it by being the fittest and best fielding team in the competition.

“I played a lot of different sports and loved fielding because it was a way I could stand out. We were so new to it though that I can still remember fielding a ball in our first game against Australia and Gary Kirsten telling me he wanted to field it because he wanted to get on television. We did not even know how long we would be in the tournament.’’

Wessels and Fenwick had never met until I passed on Fenwick’s number to Rhodes who rang with the simple message.

“Thanks for the career-defining photo … it meant everything to me.’’