Australians are the most at-risk of suffering an ACL injury: Mental, physical impact laid bare as solution floated

Australia has the highest rates of ACL injuries in the world but a leading knee surgeon says the epidemic is preventable if proper steps are taken.

Sport

Don't miss out on the headlines from Sport. Followed categories will be added to My News.

A leading knee surgeon says the catastrophic ACL injury epidemic plaguing Australian athletes from the grassroots to elite level is preventable if the proper steps are taken.

In the opening half of the A-League women’s season six players have suffered season-ending ACL injuries.

Melbourne City’s Holly McNamara’s injury was one of the more devastating as it was the third time the 20-year-old had torn her ACL and it came just days after she had been recalled into the Matildas’ squad.

But ACL injuries aren’t exclusive to football.

There were 10 serious knee injuries reported in the recent NRLW season and another nine AFLW players who ruptured their ACLs across the first nine rounds.

Dr Chris Vertullo, past president of the Australian Knee Society and director of Knee Research Australia, works closely with NRL and AFL clubs.

He said women were five to seven times more likely to suffer an ACL injury than men.

“Australia has the highest rate of ACL injury in the world and we have the highest rates of surgery in the world,” Dr Vertullo said.

“I look after two professional teams in the NRL and AFL and I see a lot more of their injured women because they are much more likely to injure themselves.

“It’s devastating for them because not only is it time out of the sport, it’s often financial and also social.

“It plays heavily on their psychology and a lot experience depression because it’s a long time out of the sport and they don’t know if they are going to get back.

“Often they are young, sometimes they are living in different cities and their whole support system just falls away.

“The psychological impact is devastating, particularly for someone who’s done it three times.”

It’s not impossible to come back from three ACL tears. Sydney FC’s Taylor Ray is back on the park after her third rupture. AFLW star Isabel Huntington made her triumphant return in September after rupturing her ACL for the third time in 2022.

MENTAL IMPACT

Sydney FC captain Natalie Tobin ruptured her ACL in the first round of the A-Leagues competition.

Tobin, 27, said the impact the injury has had on her mental health caught her by surprise.

“I just felt very low,” Tobin said. “I was feeling really fit and really good within myself so to have that all taken away was quite devastating.”

Tobin said one of the toughest parts of the rehab was watching her teammates train and play.

“I don’t want to watch people being able to run around and here is me just in the gym constantly,” she said. “People don’t really talk about how difficult it is, the mental side, not just the physical side of it.

“To just have everything ripped away from you in a split second, it’s just so cruel.”

Dr Vertullo said the mental health impact was so great 30 to 40 per cent of athletes never went back to their sport.

“A lot of that is the psychological fear of injury,” he said.

THE CAUSE

The majority of ACL injuries occur in non-contact situations. A woman’s physical build, hormones and genetics all play a role in why they are more susceptible.

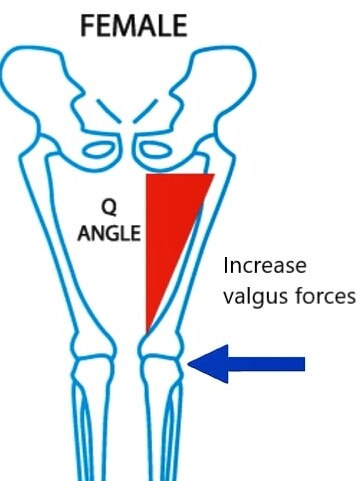

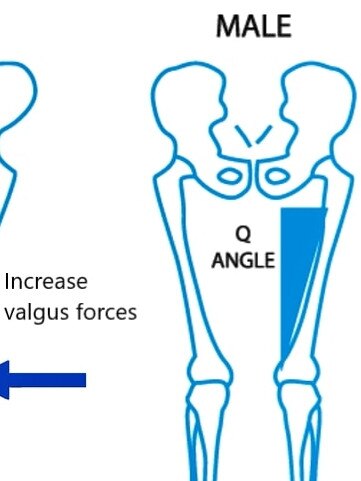

Women‘s ACLs tend to be smaller than men’s and the angle of the femur — the bone that goes from the hip to the knee — is greater in women because the female pelvis is wider.

It means a female athlete is more likely to put more stress on their knees during basic running and jumping moves.

Dr Vertullo said athletes who pushed the physical boundaries, such as elite players, had an increased risk factor.

“Because the things that make them good athletes make them actually more prone to endanger themselves. It’s not only their agility, but also, they often step faster than other people and harder and that puts more strain on the ligament and makes them more likely to rupture,” Dr Vertullo said.

“Most ACL injuries are non contact, no one actually touches them, they just step and then they tear it.”

The surgeon said most ACL injuries were preventable – especially if sport specific agility training programs were incorporated into sessions for 30 minutes, three times a week.

“Just working on your agility drops injury rates up to 50 to 80 per cent, it’s so much more effective in young women,” Dr Vertullo said.

MORE PROFESSIONAL

Brisbane Roar women’s team have lost two players to ACL injuries so far this season.

The first to go down was 16-year-old Grace Kuilamu, followed shortly after by Chelsea Blissett, 23.

It was Kuilamu’s first ACL and Blissett’s second.

Roar coach Alex Smith said both athletes had undergone surgery and were working through their rehab programs.

“They are both in pretty good spirits and are getting stuck into their rehab,” Smith said.

“With Grace she’s a young player so it’s going to be a bit of a challenge for her. Chelsea knows what to expect and how long it takes.

“While they are two important players for us, it seems like quite a larger problem in the women’s football space at the moment.”

Smith said Brisbane Roar had implemented all the recommended ACL prevention strategies.

“These girls do gym three to four times a week to strengthen the muscles and do a lot of high-performance work, from that point of view we are doing all we can,” Smith said.

“I’ve had some discussions with our doctors and the resources we have at the Queensland Academy of Sports and we are doing all we can to try to figure out if there is more we can do.”

Smith said one big step to reducing the number of ACL injuries would be to make the A-Leagues’ women’s competition a full-time professional season – not just nine months of the year.

“It’s just one piece of the puzzle but extending the length of pre-season and the off-season so the players can continue to train, a full-time program, can only benefit the athletes and help prevent some of these ACLs from happening,” Smith said.

THE SOLUTION

Dr Vertullo has lobbied for a national ACL registry for more than a decade.

All that is missing for the register is the $600,000 a year to make it happen.

“We need funding for breakthroughs and how to prevent it better and then also for breakthroughs on how to treat it better, which is something the registry would help with,” Dr Vertullo said.

“The registry aims to collect people who have an injury but don’t have surgery and also people who have surgery.

“From that we can pick up leads on the best type of surgery to have.

“I did surgery on a 15-year-old girl (this week) from soccer, she needed a knee reconstruction and a meniscus repair and as a surgeon I don’t really know the best type of graft or whether to add in extra things for someone like that. Every time we treat someone we try to individualise it but we just don’t have a great data set.”

Dr Vertullo said other nations had ACL registries, which they could access, but as sports like rugby league and Australian rules weren’t played as globally it was hard to compare data.

“I see people as young as eight who have torn their ACL playing sport and that’s quite a hard thing to treat in someone so young,” he said.

“It’s getting more common. People are getting catastrophically injured. We need more money to work out the best way to treat them and we need more money to try prevention programs nationally.”

More Coverage

Originally published as Australians are the most at-risk of suffering an ACL injury: Mental, physical impact laid bare as solution floated