The AFL high-altitude training fad that disappeared as quickly as it appeared

A decade ago, every club had to out-do each other with high-altitude chambers, but how are clubs using those million dollar white elephants now?

AFL

Don't miss out on the headlines from AFL. Followed categories will be added to My News.

It remains unclear when Essendon’s altitude chamber was last switched on.

In the back corner of the Bombers’ Tullamarine headquarters there is a small white-painted room with large rectangle windows looking into all the gathering dust.

Less than a decade ago - at the peak of the AFL’s altitude explosion - on-site altitude training rooms like Essendon’s were a crown jewel for any high performance program.

It’s where flint-hard footballers would strain for oxygen pedalling on hi-tech bikes or, in some cases, even sleep for days or weeks on end to help get a two-to-three per cent fitness edge.

In the days of the AFL’s arms race, it is estimated more than $5 million was spent on … thin air.

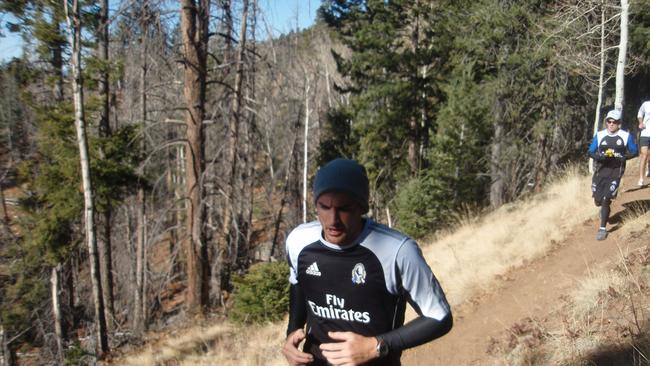

In 2014, eight clubs spent hundreds of thousands of dollars each sending their playing squads to alpine regions in the United States such as Colorado and Arizona for intense three-week training camps.

As Collingwood greats Nathan Buckley and Nick Maxwell said, the experience was brilliant for the team bonding and team chemistry, spending weeks at a time together training away from the distractions and commitments of everyday life.

But physiologically AFL training took one of its biggest turns between 2005 - 2016, when altitude camps 2000m above sea level were designed to increase players’ red blood cell count and boost their bodies’ ability to carry and process oxygen.

At altitude, the human body works harder to absorb the reduced amount of oxygen, so that when players returned to sea level, their muscle, heart and lung function were all boosted during activity.

It meant more speed, more power, greater endurance and less burn, and some of the best athletes around the globe were already investing heavily in it.

“You definitely got fitter because of the type of work we were doing,” Buckley said.

“But the real advantage was probably running around with (what felt like) a handbrake on.

“So you would just get used to being that fit with the resistance of not having 100 per cent of the oxygen your body was used to.

“There were other benefits with the camps, and they were remarkable life experiences walking up the Grand Canyon for 12 hours, or Mt Humphrey.

“Bike riding through Sedona (in Arizona). Young footballers on the other side of the world, you would have to pinch yourself sometimes.

“But training for that amount of time without the normal distractions, you definitely got fitter, and because it was so intense everything after that just seemed easier.”

The research on players’ blood cell counts suggests that the biological benefits of training at altitude lasts up to four weeks.

And to maintain a grip on the altitude advantage in-season, clubs spent huge amounts of money - ranging from $200,000 to $1 million - to build hi-tech altitude chambers.

The altitude rooms allowed players to top-up on hypoxic (low oxygen) training throughout the season in quick, regular, intensive bursts.

And clubs which didn’t have an on-site altitude room were seen to be at risk of falling behind the pack at a time when sports science in the AFL was in sharp focus, and football department spends were increasing sharply.

Collingwood pioneered the move with their first trip in 2005 and were thought to be streaking ahead by the time they surged to the 2010 premiership, triggering one of the AFL’s biggest copycat trends of the modern era.

On the field, the Magpies were also making up to 160 rotations per game, and appeared to be fitter and more powerful, racking up 20 wins from their first 22 games in 2011.

Midway through that season, superstar Dane Swan spent 12 days abroad as part of the “Flagstaff five” which helped power the jet midfielder to a Brownlow Medal after a mid-season altitude training top-up.

The man who pioneered the move, former Collingwood chief fitness David Buttifant, said the training helped catapult the Magpies to the top.

“We bottomed out in 2004-2005 and we were looking at ways to gain a bit of competitive advantage,” Buttifant said.

“I said to Mick (Malthouse) and Eddie (McGuire) this is something which can give us an edge and we saw the benefits straight away because we went straight into the finals that year in 2006.

“The boys swore by it, the way it really accelerated their preseasons and used it as a springboard into the season.”

Premiership captain Maxwell said the camps helped prime the Magpies for the 2010 premiership in multiple ways.

“Did I feel fitter? All the stats we were showed told us we were fitter,” Maxwell said.

“Definitely mentally it helped because you got to spend all of this time together.

“So, there is definitely something in that shared experience, but it is coupled with the way we actually played because we got to 160 rotations a game on average.

“And because we trained for that and we played that way, the opposition seemed to think ‘Gee, they are really fit, they are always running so hard’ and whether that was because we were getting more rest, I think it played into it as well.”

Upstairs at Olympic Park, Collingwood built a 40-person altitude chamber as part of a $10 million redevelopment, and soon enough Carlton, Melbourne, St Kilda, Brisbane Lions, Sydney Swans, Adelaide and Gold Coast all followed suit with their own altitude setups and partnerships.

Western Bulldogs partnered with nearby Victoria University to use their altitude hotel where players trained and slept.

The Suns said their altitude room “will also have a hyperoxic system built into it” which was meant players breathed in “higher than normal oxygen percentage” resulting in “many beneficial applications”.

Buckley once spent up to one month sleeping at night in a high altitude tent.

Largely, the money flowed from various corporate sponsors and donors so clubs could splash the cash on this trendy form of new training.

High-end backers even went on the overseas trips to be part of the action, and for the most part, seconds were shaved off players’ personal-best running times right across the competition.

And clubs believed the data, such as heart rate monitoring and blood profiling, all backed up the gains - to a large degree - building a rock-solid foundation for each new season.

But within two years of the 2014 boom, it was almost all over.

By 2016, only North Melbourne took about half the squad to Utah.

Collingwood and others preferred the sweltering heat of a Melbourne summer to the freezing cold of the northern hemisphere.

Heat training, sports scientists thought, could provide similar stimulus and physical stress at a much cheaper rate.

Unhappy at the arms race which had exploded, the AFL had introduced a soft cap on football department spending, tightening the spending screws in a massive way.

Fitness budgets were slashed, and suddenly, spending exorbitant amounts on two or three-week hikes, and maintaining costly high-altitude facilities for a two or three per cent spike didn’t cut the mustard.

Altitude training was soon seen as an excess, a luxury item.

Especially when the bulk of the benefits from the December-run camps literally flowed through players’ veins in January, two months from the first bounce of the ball.

Quietly, these altitude rooms have since been either torn down, or become dust-gathering relics in Essendon’s case.

Collingwood removed their gigantic altitude room and Melbourne’s was demolished to create more gym space.

St Kilda’s doesn’t exist, Carlton’s is gone and Essendon’s looks more like a glorified storage room.

It is not known whether the Bombers’ box even works anymore, or what happens when the switches are turned on.

Western Bulldogs still utilise the Victoria University facility, but for players in rehabilitation.

One club’s fitness staffer said the research showed training in lower-oxygen environment was scientifically proven to give most athletes a two or three per cent advantage.

And for cyclists, rowers, triathletes or runners, preparing for competition at high altitudes, this style of acclimatisation training were a crucial part of their preparation.

But in a team sport such as Australian rules months out from the season, the advantage was “minimal” in the context of an entire year, according to an AFL fitness staffer, and in some cases more “psychological” than anything else in-season.

“Taking a group of players overseas for several weeks of altitude training there is no doubt you would get a training benefit from that experience,” he said.

“But it was at outrageous costs.

“Massive amounts of money were going into these camps and these sorts of facilities.

“If you were going in December, and then considering what impact that would have on the regular season from March or April onwards? It was probably not a lot, to be honest.

“Definitely there were benefits in the pre-season, but it was harder to maximise in-season.

“So, to get two or three seconds off your 2km time over summer, is that really worth it from a cost benefit perspective?”

Geelong and Hawthorn never bought -in to the altitude experiment.

But Collingwood changed the game.

And from the outside, these trips and tricked-up altitude training added to a perception the Pies were fitter.

The Magpies believed it, and perhaps the opposition believed it, too

“There is no doubt it worked for Collingwood and credit to David Buttifant and Michael Malthouse,” the high performance official said.

“They created this momentum, and good on them, because they disrupted the system. And people reacted to it.

“Clubs said ‘We need to be seen to be doing that’.

“It gave them (Magpies) an edge at the time, even if it was a psychological edge.”

Professor of sports science Rob Aughey has been a leader in this field at Victoria University, and has worked with Western Bulldogs alongside highly-respected Bulldogs fitness chief Mathew Inness.

Aughey says there is “no doubt it works” but believes altitude training should now be used in a different way in AFL, considering the cap on spending and limitations on players’ training time.

Instead of expensive all-in pre-season amps, Aughey said altitude training could best help players on their way back from injury.

“It’s especially helpful for players coming back through the rehab group from injury and aren’t quite ready for the physical load of running etc,” Aughey said.

“But they can develop and maintain their aerobic fitness by using altitude and the bike.

“Doing that at altitude is going to give them that extra boost at a time when they might be more limited in terms of their volume.”

Inness conducted a study for his PHD, with positive results. Players who were subject to regular high altitude conditions recorded improved fitness results for up to about four weeks.

Aughey said there could be even better results for athletes who combine altitude and heat training, something sports scientists were continuing to explore.

“One of the studies Matt did for his PHD was looking at three weeks of a couple of sessions on the bike each week in altitude conditions and looking at how long it (benefits) lasted,” Aughey said.

“It was pushing out to three weeks or more, in some. So there is certainly a good residual effect.

“It’s giving you a boost at that time, but it’s also allowing you to do things afterwards that maybe you weren’t able to do as effectively without the altitude.”

Originally published as The AFL high-altitude training fad that disappeared as quickly as it appeared