Adrian Mackenzie was a beloved son, brother, father of two teenage boys and VFL Sandringham premiership player. He knew something was horribly wrong and desperately sought help to ensure he did not act on the suicidal thoughts that hit him with increasing regularity. It was only after he took his life that his family received confirmation he had CTE. They share his story. WARNING this article discusses suicide and mental health battles which some readers may find confronting.

-----------------------------------

A tiger clawing at his chest is how Adrian Mackenzie described the crushing sense of panic and anxiety that attacked him at night in the final weeks of his life.

The beloved VFL Sandringham premiership player and father of two teenage boys knew something was horribly wrong with his brain.

“My brain is broken,” is the only way he could describe it to his family and friends including sisters Anthea and Briohny Mackenzie.

As his health spiralled out of control, Sandringham premiership player Mackenzie checked himself into a psychiatric facility to ensure he did not act on the suicidal thoughts that hit him with increasing regularity.

The only explanation the 51-year-old could make for his inexplicable decline came from reading news stories about Danny Frawley and Shane Tuck.

The proud AFL warriors had both committed suicide, then been diagnosed post-mortem with chronic traumatic encephalopathy.

That degenerative brain disease had been caused by repeated concussions and head knocks.

And it had either contributed to or directly led to them taking their lives at their own hands.

The symptoms described by their families were eerily familiar.

Yet no one connected the dots between the constant headaches, chronic insomnia, social anxiety and suicidal thoughts that were flooding his brain to provide some answers about why he was feeling that way.

THE DIAGNOSIS

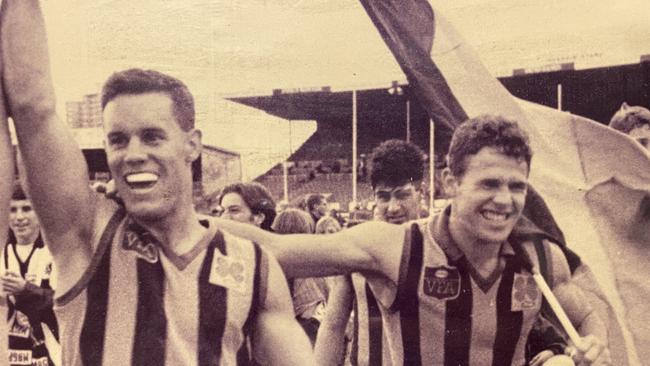

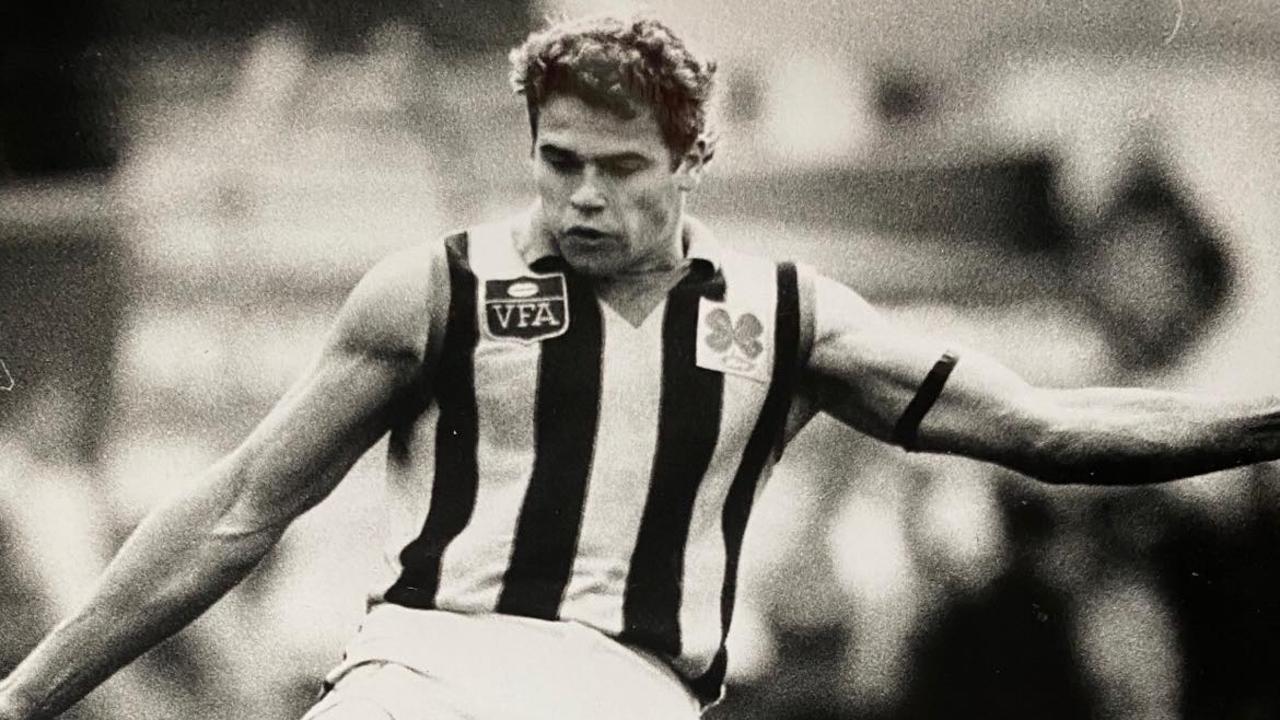

Today Mackenzie - a 1992 and 1994 premiership player with Sandringham under coach Trevor Barker - is revealed as the fifth footballer to be confirmed as having suffered CTE.

Mackenzie took his own life in the last week of May 2021, hailed by his former teammates as a great clubman, team player and “fearless in his attack on the ball”.

Six months after his brain was donated to the Australian Sports Brain Bank in 2021 he was diagnosed with stage two CTE.

Unlike Frawley and Tuck, Collingwood’s Murray Weideman and AFL legend Polly Farmer, Mackenzie had no level of AFL fame or stardom.

But like Frawley and Tuck, his family wonders if he would still be alive if he could have found the answers he was looking for instead of taking his own life.

And they wonder how many middle-aged men with long suburban or country careers who have committed suicide with an undiagnosed CTE diagnosis.

“He knew that his brain wasn’t right,” says sister Anthea, who has made it her mission in the past 18 months to educate herself on CTE.

The Mackenzie family is finally ready to tell Adrian’s story - in part to raise awareness for CTE’s effects but also to explain to friends why he might have ended his life when he had so much to live for, starting with those two teenage sons.

She was so concerned over the management of Mackenzie’s plight she lodged an official submission to the current senate inquiry into concussions and repeated head trauma in contact sports.

“We weren’t sure and then it came back that he had stage-two CTE. And that was what he kept saying to us in those final weeks, ‘My brain is broken’,” she says.

“He had bouts of social anxiety, but he was adamant he wasn’t depressed.

“He said it wasn’t a mental illness but his brain was broken but there just didn’t seem to be those conversations happening with his medical practitioners.

“For me what stood out was the terms he used about the anxiety and panic he was feeling. And the fear he had about killing himself. He would compare the anxiety he had to a tiger being on his chest clawing at him. That is the panic.

“When I think about that night, he was in such a panic.”

REMEMBERING A GREAT MAN

Ask his sister Briohny to describe her brother and the tears flow immediately.

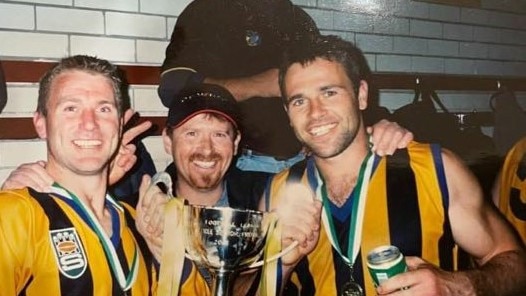

“Good looking…. Sportsman. Girls loved him. He had everything. A good business, successful. Two young boys.”

Anthea adds: “We called him the golden child. He hated that. But he was very loved by everybody. I actually think he was the glue that held the family together.

“We haven’t had a whole family get-together since Adrian has passed. Because he would be so missed. If you knew Adrian was going to be there, you wanted to be there too.”

The son of Sandringham Zebras great Darrell Mackenzie, Adrian had a stint at St Kilda’s Under-19s then followed in his father’s footsteps at the club where Darrell became a VFL legend.

Adrian ended up playing 72 senior games at Sandringham including those 1992 and 1994 flags under the brilliant Barker, who would pass away at the age of 39 and only two years after that second premiership.

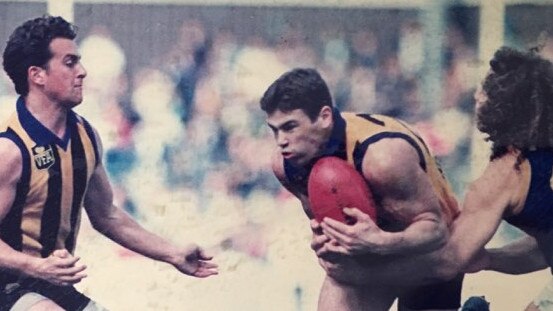

The charismatic and popular Mackenzie was at the bottom of every pack showcasing his renowned toughness before stints at the Nar Nar Goon and Hampton United football clubs.

Like any player plying their trade in that extremely physical era he would have given out and received countless hits, although his number of concussions was never tallied or even spoken about.

“He was always known as that hard, tough player,” says Briohny.

From his mid-20s he had occasionally spoken about a level of anxiety as he battled with sleeping issues and headaches.

But in early 2021 more than a decade after his career ended his symptoms dramatically escalated, a common occurrence for those who are diagnosed with the degenerative brain disease.

THE RAPID DECLINE

Briohny Mackenzie was shocked how quickly he found himself in crisis.

“He just rang me basically telling me how quickly he was struggling. And it was the sleep. It was a big issue for him. He rang me up and just started crying. It was so out of character. “You could tell how desperate he was to have the conversation. Then he would go for a jog to clear his head and then he would spiral again a few days later.”

He complained about “brain fog”, started making irrational decisions, was hit by constant headaches that only now Anthea realises are the tell-tale symptoms of CTE.

“It was distressing towards the end. It seemed to spiral quite quickly once he let us in on what was happening,” she says.

Mackenzie checked himself into a psychiatric facility twice but after his second stint was discharged and told to check back in a fortnight.

Those doctors prescribed him a litany of medicines - Mirtazapine, Olanzapine, Lexapro, Propranolol, Imovane, Circadian, Valium, Temazepam, Seroquel, Ritalin, Kalma.

As Anthea said in her official submission to the senate inquiry: “It is our understanding that none of his medical practitioners discussed CTE with him. We feel certain that if CTE had been discussed with Adrian this would have been a lifeline for him.”

He was searching for answers to drag himself out of that spiral but didn’t believe any of those solutions would provide respite.

“We don’t think it was ever discussed with him by any of the medical people he saw. It wasn’t recognised that he could have this. He only briefly mentioned to me one of the last times I saw him,” says Briohny.

“He said, ‘I am going crazy, I think I have got this thing that Danny Frawley had’.

“He had mentioned that he thought he had it based on reading stories in the paper about Shane Tuck and Danny Frawley.”

HIS FINAL DAYS

By early May 2021 Mackenzie was asking his family and friends to be part of a roster to stay with him at night so he avoided self harm.

“He was very aware that he was suicidal. And he was very clear that he did not want to kill himself.

“But he was having those thoughts. He was reaching out and saying, ‘I need help here’”, says Anthea.

On the night he took his life he had been planning activities with his boys for the school holidays, had ordered his Coles shopping online.

But on that fateful night he did not have company, his family reassured by his release from the psychiatric hospital that he was making progress.

And yet for Adrian Mackenzie, the tiger conquered all those rational thoughts about having a purpose to survive.

“His ex-wife rang me,” says Anthea.

“And she had gone around to his house to check on him in the morning. And she called me and said, “He’s gone….”

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy can only be diagnosed post-mortem but the family strongly believes he would still be alive if his downward spiral had been managed differently.

“There is no doubt in my mind that if (CTE) had been raised as a possibility it would have been a lifeline for him,” says Anthea.

“It would have been a hope that it could be managed. There may not be a cure, but we can manage it.”

As Anthea says in her official submission: “We urge the government to encourage medical practitioners to review procedures when diagnosing patients with a history of playing contact sport.

“Adrian was actively seeking and trying therapies to manage his symptoms beyond prescription medications because he was adamant that he did not have a mental illness or depression, but that his brain was ‘broken’.

Briohny wants Adrian’s sons to know that there was a reason for their father’s loss.

“I think it’s important for his boys. This can give them some sense around why he did it. If we can bring some awareness to that, that he didn’t have depression. CTE was behind this. It does help his boys to know that it’s not a genetic thing. He didn’t just leave us,” she said.

“When there is a suicide there is a lot of what ifs. So to get this diagnosis and to know Adrian felt there was this possibility brings an enormous amount of peace. And also some purpose. How do we bring awareness to this issue for other people?

DIAGNOSIS POST MORTEM

Michael Buckland is the founder and director of the Australian Sports Brain Bank and the department head of neuropathology at the Royal Prince Alfred Hospital in Sydney.

He examined Adrian’s brain - specifically looking for the abnormal forms of tau protein that collects in the valleys of the brain in a manner very distinctive to other issues like Alzheimer’s disease.

He says the data collected from the first 21 brains analysed by the Australian Sports Brain Bank makes for sobering listening.

“We published an article in the Medical Journal of Australia last year of the first 21 brains examined and of those 12 of the 21 had CTE and 12 of those people who had CTE had died of suicide. We now have close to 60 brains analysed and those statistics are still holding up. We are unable to draw a causal link between CTE and suicide but on face value the relationship is very disturbing.”

He says scientists are some years away from being able to diagnose CTE in living patients but is hopeful experts will soon be able to build a picture from a range of tests that will give potential sufferers some clarity.

“The way we will end up is there will be a whole range of clinical signs and symptoms which are suggestive as well as a PET scan, probably blood tests, biomarker tests and when you add those together in the future we will be able to make a reasonably accurate diagnosis.”

For some sufferers knowing their actual diagnosis is not depression will help, but there are already ways to mitigate the symptoms of CTE.

A 2020 Lancet study on dementia prevention and care listed ways that Buckland describes as solutions to “take back control of your destiny”.

They include brain training and plasticity, managing weight and blood pressure, managing blood sugars.

In its recent submission the AFL acknowledged the link between CTE and repetitive head knocks, drawing on a recent definitive statement on that topic from the National Institutes of Health, America’s medical research agency.

The league has committed $25 million over a 10 year period on a longitudinal study into CTE but is yet to set any terms of reference.

“A longitudinal study that is appropriately funded, designed and conducted is a good thing,” says Buckland.

“But what is the purpose? If it is going to be used as an excuse to kick the can down the road, that is not good. If it is to look at clinical signs and symptoms so people can get treatment later in life that is a good thing and we would love to be consulted and work with them. That is yet to happen.”

Concussion campaigner Peter Jess has advocated for concussion passports for all AFL players so they have a specific record of how many times they are concussed from their first days of football.

Buckland believes the new trials into mouthguards like the HITIQ mouthguard which measure all knocks - concussive and sub-concussive - will eventually shape the league’s head knock strategy.

“In the future anyone who wants to play a lot of footy might wear one. In summer you have a rough idea of how much sun you get on a really hot day. It might be the same with head impacts. You can monitor it with an accelerometer which will measure it for you and determine your risk of CTE. If you have had too many knocks, you might be considering retiring in the next few years so why not do it now?

Anthea Mackenzie is now in regular contact with Shane Tuck’s sister Renee as she pushes concussion education programs in her local community including the football club and school where she teaches.

She hopes the senate inquiry findings might force more progressive policies onto sporting organisations but “I also think it’s beyond sports”.

“The research shows that when we talk about veterans and other sporting codes.

“Also in Australia there is a culture of masculinity and what it means to be a man. Working with teenage boys and seeing how they play…”

Her recommendation in her senate submission was that if medical practitioners know they are treating a patient who has played contact sport they raise the possibility of CTE.

Mostly, though, Anthea Mackenzie wishes she could have her brother back.

“We didn’t have that CTE diagnosis when his funeral took place. So the possibility of CTE wasn’t mentioned. There was still a lot of shock and confusion. But at least this has given everyone answers.”

Add your comment to this story

To join the conversation, please log in. Don't have an account? Register

Join the conversation, you are commenting as Logout

AFL star cops ban for ugly act on rival

Toby Greene has been handed down a suspension for an ugly act on a Sydney rival during Friday night’s blockbuster clash.

Premiership race rocked by record-breaking Suns in QClash

Gold Coast have thrown a spanner in the top-eight mix with a crushing defeat of their crosstown rivals Brisbane. Get the reaction and details here.