The two things Bob Hawke never lost faith in

Bob Hawke was a man who worked hard and played hard. The longest serving Labor Party prime minister — and one of the country’s most successful — never lost faith in two things, writes Dennis Atkins.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

We know Bob Hawke was a man of destiny because he told us so.

He was repeating what he was told by his doting mother Ellie who recounted the story from the time of his imminent birth.

Ellie’s daily Bible reading would take her to the early pages of Isaiah when she settled, again and again, on the passage which said “For unto us a child is born, unto us a child is given: and the government shall be upon his shoulder … ”.

RELATED: Bob Hawke’s biggest achievements

Hawke was a man who worked hard and played hard. The longest serving Labor Party prime minister — and one of the country’s most successful having won four elections in a row — took up a job with the Australian Council of Trade Unions after completing a Rhodes scholarship thesis on wage fixing in Australia in the mid to late 1950s.

His first splash in the national press was in 1959 when he argued successfully a national wage case which rewarded workers with a better than expected 15 shilling weekly pay rise.

RELATED: Former prime minister Bob Hawke’s most colourful quotes

Hawke has never been out of the media spotlight since.

In the following decade Hawke worked to achieve a first step on his way to national political leadership — election as the president of the ACTU which he secured in 1969, ironically with the help of leading left wing union leaders including Ray Gietzelt.

Hawke quickly gained a reputation as the industrial fixer who would broker outcomes in disputes and settle strikes — quite often to the satisfaction of both workers and employers.

The ACTU years

During the brief, turbulent years of Gough Whitlam’s Government, Hawke was not just ACTU president but also national president of the Australian Labor Party.

While he had a controversial role in backing exorbitant wage rises during the Whitlam years, he was credited with calming a potentially riotous Labor movement after the Governor-General Sir John Kerr sacked the Government and installed the Coalition.

The subsequent seven years saw Hawke work hard on the rehabilitation of Labor’s image as an economic manager which had been all but trashed during the Whitlam years.

RELATED: What Bob Hawke really learnt at Oxford

However, Hawke wasn’t about to do the opposition leader Bill Hayden too many favours because he wanted his job, so he could fulfil the destiny his mother had seen foretold in Isaiah.

As well as burnishing his own credentials as a national leader, Hawke cleaned up his private behaviour mainly by quitting drinking — an indulgent habit which added to his notoriety but did nothing to make many people think he could lead the country.

He also scaled back his equally infamous womanising and laid out his life, warts and all, in an authorised biography by Blanche d’Alpuget (who he later married).

RELATED: Tributes flow for former Prime Minister Bob Hawke

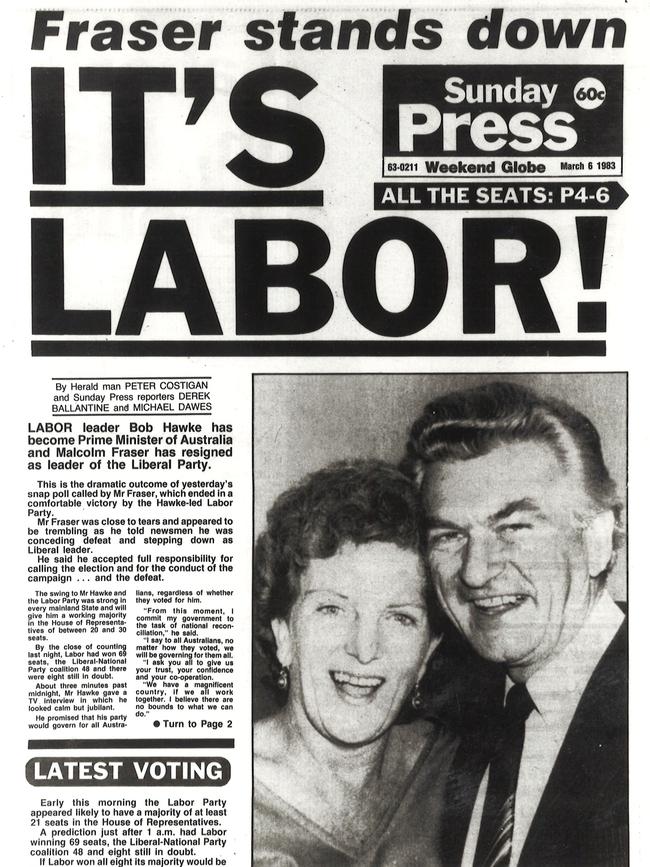

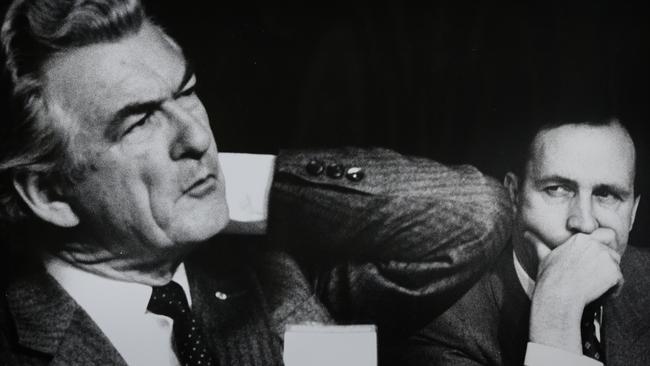

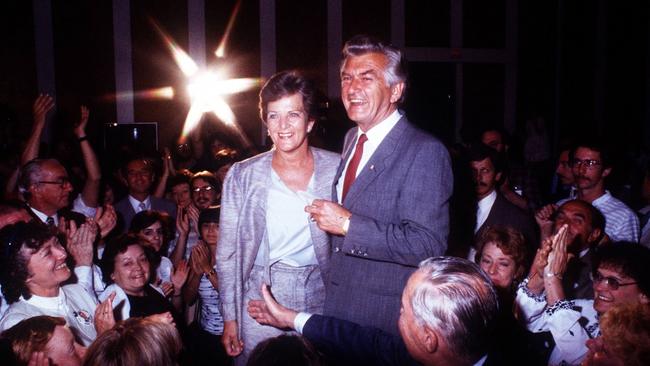

Hawke challenged Hayden in mid-1982 but his tilt fell short. His supporters struck again in the shadows of Liberal Prime Minister Malcolm Fraser calling an election six months later and Hawke became Labor leader just weeks before the 1983 poll.

Winning government

Hawke’s election as Australia’s 23rd prime minister ushered in what’s still seen as a golden age of national reform and economic restructuring.

The dollar was floated, the banking system opened up to competition, interest rates were left to the market and a historic tripartite agreement between government, the unions and business — the Accord — moderated wage growth in exchange for sweeping social change such as Medicare and means-tested welfare.

This was Hawke’s grand design. Some of it had been exposed in his 1979 Boyer Lectures, although he left behind the more radical proposals from that time, such as scrapping state governments and including outsiders in federal cabinets.

Both those lectures and the big plans he rolled out in 1983 and 1984 showed Hawke as one of the great long-term thinkers we’ve had in the prime minister’s office.

Soon after his victory, he gathered the movers and shakers of national policy — state governments, business lobbies, welfare groups, trade unions and academic economists — to forge a consensus on where Australia was headed.

Hawke and his treasurer Paul Keating, teaming up with ACTU secretary and co-conspirator in the great reform plan Bill Kelty, already had the framework of what they wanted in their minds. The short-term was topped by the Accord which Hawke wanted to put a lid on wage demands while providing cover for welfare reforms aimed at the middle and lower income groups.

The long-term, which was a germ of an idea in the collective minds of Hawke, Keating and Kelty, was crowned by compulsory superannuation.

A wage rise that had been in the early 1980s diverted to national super was, by 1992, rewarded with payments from employers on top of wage rises. It created a national superannuation system unlike any in the world.

Balance family and work

All of this happened under Hawke’s guidance as the chairman of the Cabinet. He has said, and his ministers agreed, he ran the engine room of policymaking unlike other prime ministers in the modern era.

Hawke didn’t often exercise his “majority of one” but rather let his ministers argue their case, take debates back and forth and sought consensus. It was his natural inclination throughout his political career.

RELATED: Tony Abbott’s surprise Bob Hawke statement

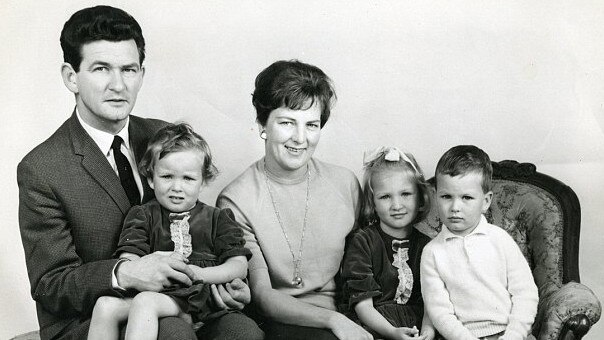

Hawke’s home life was going through a crisis as he fought his first re-election bid in 1984 — a snap early poll aimed at cementing power.

His daughter Rosslyn was in the grip of heroin addiction and, stung by a charge by then Liberal leader Andrew Peacock he was soft on drug crime, the prime minister gave a raw, emotional press conference during which tears flowed down his cheeks.

Running on 50 per cent energy and creativity at best, Hawke was lucky to survive that election but he bounced back, reverting to his old trick of holding a summit on tax.

Under pressure from the ACTU he walked away from a goods and services tax, leaving the champion of that proposal, treasurer Keating, high and dry. The rest of the reforms were significant enough, including Australia’s first capital gains tax and the ditching of exemptions for entertainment and other deductible work expenses.

Economic headwinds

The economy started to falter in early 1986 with Australia’s trade deficit jumping 41 per cent in April, while the current account deficit reached 6 per cent of GDP and the dollar fell 3¢ in one day.

Keating warned the country was in danger of becoming a “banana republic” — a statement aimed at shocking the public into a new reality. By the next year, the economy was back up off the floor, Hawke was in better form and the 1987 election made up for the near death experience of the poll in 1984.

Hawke increased his majority and returned to the parliament dominant and full of new life.

In 1988 Keating presented a Budget which made up for what had been five years of hard grind of cutting expenditure and getting the deficit under control. It was, said the treasurer, the one which “brings home the bacon”.

The Budget gave the biggest boost to the key Labor priorities of welfare, education and health but this was not enough for many in the parliamentary party who were tired of selling the new austerity to voters.

The Labor PM reminded his colleagues the government had created one million new jobs and had boosted school retention rates from 33 per cent to 53 per cent.

This was all being done, he thundered, with the aim of building a long-term Labor Government which was the only way to cement lasting social and economic reform.

He emphasised at the Caucus meeting “the unique opportunity for members to be in government for more than a decade”.

Leadership challenged

This was one of the driving passions of Hawke as a leader.

His longevity was tested as the government inched towards the 1990 poll with their standing in the polls slipping.

The country, still adjusting after the late 1987 stock market crash, was fighting with the contradictions of squeezing monetary policy by hiking interest rates while increasing spending and cutting taxes.

Hawke squeaked back into power at the March 1990 poll. Then a deal hatched two years earlier returned to explode on the national scene.

In 1988, Keating, impatient to have his time as national leader, demanded an agreement with Hawke ostensibly giving Keating the prime ministership after the 1990 poll.

Keating leaked details of the secret Kirribilli agreement and threw down a challenge to his leader in mid-1991.

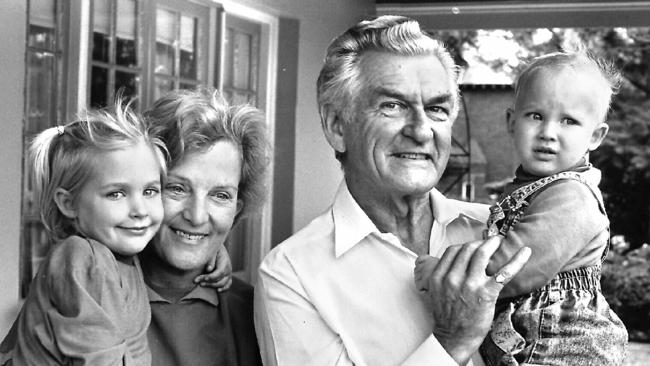

Hawke left parliament in early 1992 and, after marrying d’Alpuget, settled into a harbourside life in Sydney. He carved out work as a consultant to firms doing business in China where he was regarded as the greatest of Australian leaders.

He campaigned for Labor at every election when he was able until his death. He never lost faith in two things: his own greatness and the Labor movement to which he devoted his whole life.

Dennis Atkins is The Courier-Mail’s national affairs editor.

dennis.atkins@news.com.au