Our political system isn’t broken

DESPITE online meltdowns despairing at our revolving door of PMs, volatility in the top job isn’t terminal. But our major parties do suffer from unappealing flaws, writes Paul Williams.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

MOST Australians were appalled by the events in Canberra last week.

That’s supported by yesterday’s Newspoll that saw the Coalition’s primary vote crashing to 33 per cent (eight points behind Labor) and after-preference support for the Opposition blowing out to 12 points, 56 to 44. Worse still for the Coalition, new leader Scott Morrison trails Bill Shorten as preferred PM, 33 points to 39.

Yes, it appears the court of public opinion has already passed judgment: if the Liberals can’t govern themselves, they can’t govern the country.

The online meltdown last week revealed four types of reader reactions: “pollies should stop bickering and start governing the country”; “stop looking after yourselves and start looking after the little people”; “political parties don’t have the right to dump a prime minister we voted for”; “there should be a law forcing prime ministers to complete their term”.

In the first two examples the sentiments are understandable. No one can deny the revolving door of PMs — seven in 11 years and five in five — makes Australian democracy look shaky. Just compare that record to the 15 years between 1950 and 1965 where we had just one PM (and just three Labor leaders), or the 19 years between 1976 and 1995 where we had three.

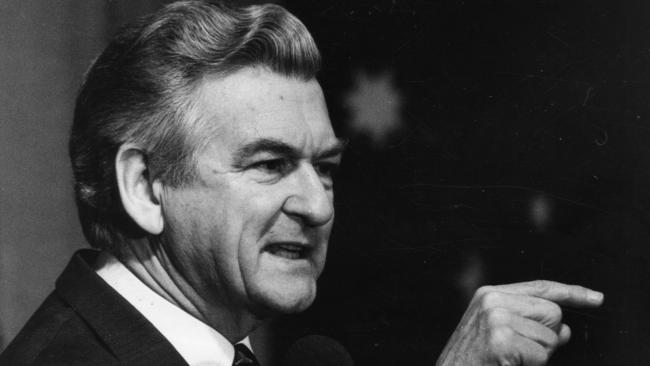

My daughter, who’s six, has already seen five PMs, but I argue our most recent period of leadership volatility won’t be permanent and, therefore, not as damaging as many suspect. Personally, I’d seen four PMs by my fifth birthday, and six before my tenth before entering a long period of stability under Malcolm Fraser and Bob Hawke.

The system, then, is far from broken, but I must concede our major parties do suffer unappealing flaws.

The first is that the Labor and Liberal parties are broad ideological “catch-all” churches who want to appeal to all Australians. On one level, it’s a noble thing to govern from the “centre”.

But a broad church also means housing very disparate beliefs. That’s why the Labor, Liberal and National parties each contains at least two (and probably more) factions, tendencies or parties within a party.

Labor, for example, has a left that prioritises human welfare while the right prefers pragmatic policy around jobs and wages. Similarly, the Liberal wets want a bigger welfare net for the disadvantaged but keep away from personal moral issues, while the dries say folk ought to stand on their own financial feet and adhere to (Christian) family values. Even the Nationals are still divided over whether globalisation and free trade have helped or hindered our farmers.

For good or bad, the reality is the major parties will never wholly agree — within themselves or across the board — to “put aside their differences for the sake of the national interest” because the “national interest” means something different to every voter. What the major parties must do, then, is better manage their factional conflict by giving minority interests representation in all party forums.

A second flaw is the major parties’ dependency on opinion polls, with too much following of public opinion and not enough leading. Unsurprisingly, voters see this as weak, and they lose confidence accordingly. The only solution is for the media to reduce the number of polls they commission, and for journalists to report politics outside “horse race” frames of who’s “winning” and who’s “losing”. But that’s not going to happen.

But it’s the second pair of comments that are truly nonsense. Another reality is that we live in a Westminster parliamentary system and not a presidential one. We don’t directly elect our PMs in the same way Americans elect their presidents. Therefore, we don’t “own” a PM in the same way Americans own — and are stuck with for four years no matter how appalling — their president.

We might think our PMs are popularly elected celebrities directly answerable to voters, but they’re not, and never have been. Our centuries-old Westminster system has carefully evolved so that PMs are first accountable to their Cabinet, then to (more recently) the party room, then to the Parliament, then to the people — in that order. In short, the Liberals’ party leadership is — and should be again in Labor’s case — awarded and removed by the party room.

So, before we condemn MPs who, like the rest of us, live in an image-obsessed social media age, can we really blame parties for installing leaders most likely to appeal to us? Isn’t it their duty to offer voters the most palatable options in both policy and leadership?

Look in the mirror — or your selfie stick — before you cast the first stone.

Dr Paul Williams is a senior lecturer at Griffith University.