On the citizenship survey, Hanson may be right

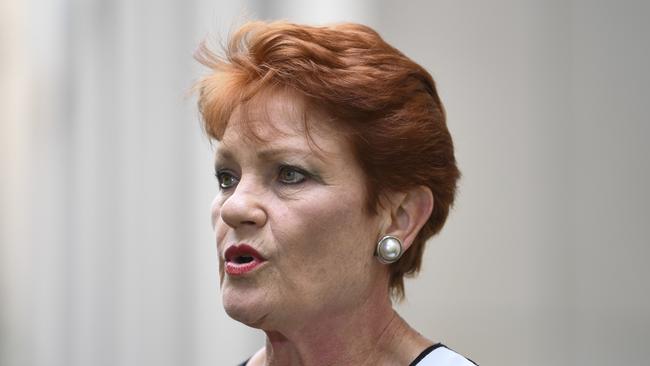

LOVE her or hate her, the One Nation leader has a point in saying that anonymous online surveys have no place in the making of Australian laws, writes James Morrow.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

SENSITIVE readers may cringe at the thought, but what if it turns out that Pauline Hanson is right?

What if, as she told the Daily Telegraph this week, an online survey to take feedback on her proposed legislation to lengthen the time permanent residents need to live in Australia before becoming citizens, really has been gamed by foreign interests?

For those who have not yet taken to their fainting couches, a little background.

It all started a month ago when the Senate’s legal and constitutional affairs legislation committee took the nearly unprecedented step of setting up a SurveyMonkey online poll to ask one question: “Do you support the provisions of the Australian citizenship legislation amendment (strengthening the commitments for Australian citizenship and other measures) bill 2018?”

Participants had to provide a name — any name — and an email address to take part.

Never were participants even asked if they were eligible to vote in Australia. Nor was there any safeguard to ensure that people (or bots) couldn’t vote multiple times.

If you wanted to set up a way to encourage activist groups to push through a big vote against the changes and provide a counterweight to Hanson’s amendments, you’d be hard pressed to find a neater solution.

Either way, the whole idea of legislating by SurveyMonkey is bonkers.

And, as this newspaper reported, groups foreign (the Australian Oriental Media Network and the Honourary Brazilian Consulate in Brisbane to name just two) and domestic (the Multicultural Communities Council Gold Coast for example) fired up their Facebook pages to urge followers to “have their say”.

This is nothing new. From politics to pop culture, groups from one side or another regularly direct their fans to online polls hoping to get their side over the line in some ultimately inconsequential bunfight.

But the question of how we as a nation decide who we admit into our national family as citizens is a bit more weighty than what name we want for the new royal baby or who was in the right in the latest reality TV catfight.

Of course what is alleged hardly rises to the level of the putative and as yet unproven Russian meddling alleged to have occurred in the US election. Though presumably one of these days the FBI will have the smoking gun that proves Moscow kept Hillary Clinton from campaigning in Wisconsin and Michigan and Pennsylvania.

But as Hanson said, the participation of these groups, particularly ones with links overseas, in the process means that “they’re interfering in our laws and our citizenship.” Or at least the process by which we make laws about citizenship.

Which of course brings up bigger issues about who should be allowed a say. Don’t for a moment think that the idea that only citizens should be able to vote is settled: particularly among the progressive, academic left, the idea of broadening the franchise and diluting the idea of national loyalty is gaining popularity.

Last year the University of Melbourne’s Heath Pickering wrote for SBS that it was not fair that “millions of foreign-born legal permanent residents living in Australia can’t vote … this is despite living, working, paying taxes and using public services like schools and Medicare.”

And there is also the question of direct democracy, which is generally frowned upon as too chaotic for parliamentary systems like ours.

This is not to say that there is no place for giving people a more immediate voice. Last year’s postal plebiscite on same-sex marriage was, for all the objections, ultimately an effective way to drive through a major and contentious social change while ensuring all sides had buy-in.

Perhaps if the Senate really wants to put Hanson’s questions to the people, and not through some easily gulled survey website, they might try something similar with regard to, say, the issue of just how fast our population should be growing.

But then, as the saying goes, you shouldn’t ask a question you don’t want to know the answer to.

James Morrow is Opinion Editor of the Daily Telegraph.

Originally published as On the citizenship survey, Hanson may be right