Coronavirus is just the latest in our doomsday concerns

Panic over the potentially deadly threat of coronavirus has peaked, but it’s just the latest scare in a long and colourful history of our worrying, writes Michael Madigan.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

What may have started inside a bat in a Chinese cave may yet spread across the world and redefine the doomsday debate which has transfixed the world since the first disaster movie script appeared in the Bible’s Book of Revelations.

The coronavirus now menaces the globe with the spectre of a worldwide pandemic – a prospect which focuses the mind far more sharply than climate change, which only provides for humanity’s partial annihilation somewhere in the far off future on an unspecified date.

The Bubonic Plague which hit Europe in 1347 was far less ambiguous about its Day of Judgement intentions – it reportedly killed off at least one third of Europe in 60 years.

Yet the Black Death, for all its sinister intent, wasn’t quite the Apocalypse that the world has been on edge about for the past 2000 years.

It wasn’t until 1945 when the first atomic bomb exploded in New Mexico, its 10 kilometre high mushroom cloud signalling to the world the birth of the atomic age, that centuries of unease about Judgement Day crystalized into serious foreboding.

Throughout the 1950s the grim prospect of a nuclear annihilation wove itself into the collective consciousness of a developed world growing more connected by mass media, heavily influencing literature and popular culture.

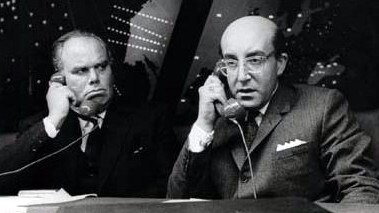

The high water mark for “annihilation art’’ may well have been Stanley Kubrick’s cinematic version of a resigned shrug in his 1964 film Dr. Strangelove or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Bomb.

By the 1970s we were moving away from a fixation on nuclear annihilation towards a slower moving apocalypse represented by the birthrate.

The best selling book The Population Bomb’ was published in 1968 and sparked a marathon debate about whether we could actually breed ourselves into extinction, with warnings of global wars over depleting food resources and famine.

An Iowa farm boy largely forgotten by history, Norman Borlaug, gave us a solution to that problem by devising new high yielding wheat varieties which massively increased food production.

As Australia moved through the 1970s we demonstrated a capacity to localise annihilation, with a tsunami prophesied to hit South Australia in 1976 as divine retribution for progressive laws on homosexuality.

Premier Don Dunstan, clad in a fetching safari suit, walked on to Glenelg Beach and, holding forth his hands toward the horizon, pledged to personally hold back the monster wave.

It seemed to work and by the turn of the century, with the surf still reasonably moderate along the southern coast and the Population Bomb still waiting to detonate, the problem of rising global temperatures caused by the burning of fossil fuels was captivating a world about to grow even more closely connected via social media.

In the decade ahead it’s quite possible that our focus on climate change’s rising seas and raging droughts could well be sidelined by a preoccupation with medical science.

Coronavirus and its inevitable successors could swiftly come to dominate public debate with the quality broadsheet media providing a platform for experts from the medical side of the scientific world rather than the earth sciences.

Pandemics and advances in combating them could soon provide endless fodder for middle class dinner party conversation, provided of course a stray asteroid doesn’t plunge through the dining room ceiling and redirect our ancient anxieties back upward toward the stars.

The odd thing about doomsday debate is not so much that all our post-war fears have never been realised; it’s that they’ve never been resolved.

Rapidly rising populations, especially in Africa and Asia, still pose enormous challenges, the scientific community is largely united on the very real threat posed by climate change, unhinged people still have access to nuclear weapons now ten times more powerful than their 1950s counterparts, asteroids still whiz by missing us by a handful of light years and while the Bible’s Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse haven’t yet arrived, there’s no reason to believe they won’t saddle up and gallop by any tick of the clock.

The uncomfortable reality is that being human means spending much of our time gazing at looming catastrophes, the most unsettling one of which is our own death.

We may have come up with a magnificent array of alternatives to distract us from that one disaster far less speculative than any other, and one which neither science, medicine nor even the magnificent Don Dunstan in a safari suit, can shield us from.

Our own personal doomsday will, quite definitely, arrive soon enough.

Michael Madigan is a columnist for The Courier-Mail.