Coronavirus Australia: Welcome to life inside a COVID-19 ‘fever clinic’

Unanswered calls to the hotline, hours in triage with sick patients and overwhelmed nurses — if my experience is any indication, Australia is not ready to handle a pandemic, writes Jennifer Dudley-Nicholson.

Rendezview

Don't miss out on the headlines from Rendezview. Followed categories will be added to My News.

There are 11 sick people in the waiting room and no one wants to sit beside anyone else.

A cleaner wiped down each seat before they arrived but was chastised for using just one antibacterial wipe on all of them.

Instructions to sit one seat away from other patients are no longer being followed either — there are too many people — so some of us linger in the corners while filling out paperwork.

The nurses in charge are clearly overwhelmed, doing their best to address everyone who enters and ask them about travel movements, while breathing into duck-like face masks and changing their gloves with every action.

I notice the woman who triages me touch her spectacles with dirty gloves. I try to tell her but she’s already touching her hair. I hope everyone here just has the flu.

This is life inside one of Australia’s new ‘fever clinics,’ specialised treatment facilities within hospitals designed to divert potential COVID-19 sufferers away from GP offices and regular hospital wards.

If today’s attendance becomes standard, Australia is going to need a lot more of these.

In fact, we’re going to need a lot more support in general because, as it stands, Australia is not ready to handle the novel coronavirus outbreak.

If you’ve landed in Australia from a heavily infected country in the past two weeks, you’re probably well versed in ‘self isolation’ procedures.

But if you arrived earlier, if you came from a country slipping under the radar, you might have no idea what to do when a fever, cough, sore throat, runny nose, or respiratory distress arrives.

Like Missy Higgins’ doctor father, I returned to Australia from the US, which had no known cases of coronavirus at the time.

During the journey, I was careful to touch my face as little as I could, wash my hands often, and avoid anyone who looked ill.

And, when I was later notified that I’d been in the general vicinity of someone confirmed as having the disease, I dobbed myself into my work’s human resources department, 18 days after my return.

It was only when I came down with a runny nose, a cough and a fever that I realised I could have a serious problem. But what do you do when there’s a slim chance you are spreading a pandemic?

You could, for example, call the national coronavirus hotline. Australia has one of those now.

If you’re after medical advice, it will transfer you through to a state-based helpline offering a chat with a registered nurse.

I stayed on the phone listening to didgeridoo sounds for 40 minutes on that hotline. No nurse answered.

You could try to talk to a registered nurse on a helpline operated by your private health fund instead. I stayed on the phone listening to advice about eating vegetables for 40 minutes on that hotline. No nurse answered.

You could talk to your local GP about being assessed. Mine instructed me not to come anywhere near the practice.

Call a helpline, they said.

And when people run out of options, like I did, they do two things: they give up and go to work, or they head for a fever clinic.

You’d hope people would try the latter, even though they could be sitting in a waiting room filled with face masks, nervous staff, and violent coughing.

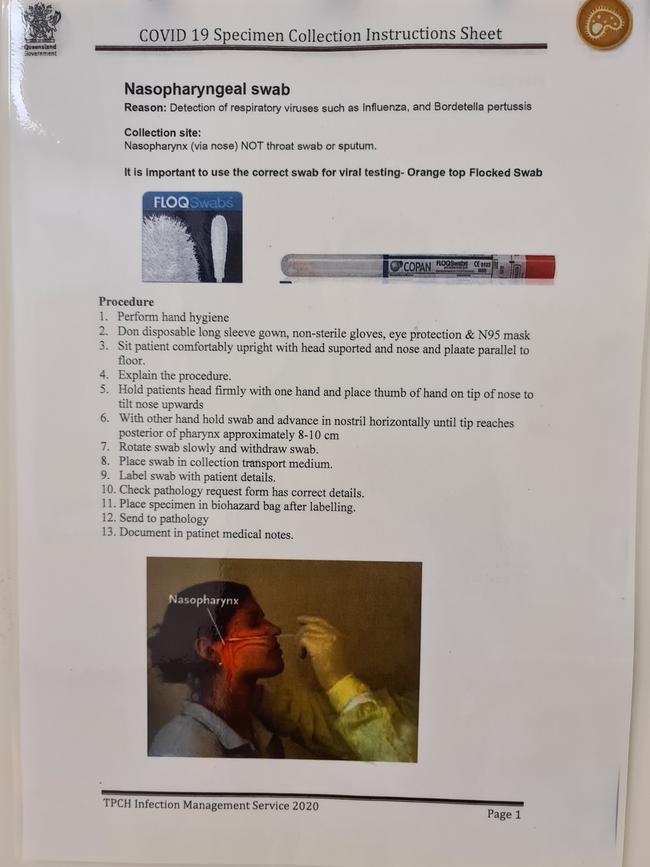

And then you’d hope they would endure the long waits to see a doctor (two hours before I got swabbed).

But, if the sick and sneezing don’t bother, and if fever clinics aren’t adequately staffed and resourced, the outcomes could become much more grim.

Australia is faring better than many other countries when it comes to coronavirus so far, but there needs to be a lot more information, a lot more resources thrown at it, and a clear path for testing this flu season.

Ailing people need to know where to go to protect others, and it’s got nothing to do with the toilet paper aisle.

Jennifer Dudley-Nicholson is News Corp Australia’s national technology editor